There are many ways to see things. Every reasonable perspective adds a dimension to understanding and appreciation.

- To see a world in a grain of sand / And heaven in a wild flower / To hold eternity in the palm of your hand / And Eternity in an hour. [William Blake, “Auguries of Innocence”]

- The flow of the landscape into the image of Lisa is the ultimate expression of Leonardo’s embrace of the analogy between the macrocosm of the world and the microcosm of the human body. [Walter Isaacson, Leonardo da Vinci, (Simon & Schuster, 2017), p. 487.]

Having a perspective (point of view) is not the same thing as having perspective. Everyone has a point of view but not everyone can see or tries to see things from many points of view. This way of walking in the shoes of others is essential to intellectual, ethical and spiritual development. Its equivalent is also essential to creativity in science and the arts.

The word “perspective” can be used in two senses. One is in the usual sense of having a perspective on things: an object will look different from one vantage point as opposed to another.

The other sense is a deeper view into the first. A good perspective may be inaccessible from too close. Obtaining a good perspective on the whole can require us to step back and consider the object from a greater distance.

This second sense is the one intended here. It is the defining characteristic of the Renaissance Man. It stands in contrast to the idea of the narrow focus. As some people work most productively when focused narrowly on one subject, others seem to be most productive as generalists. This mixture of talents adds richness to the contributions each of us makes to the whole.

Real

True Narratives

Book narratives:

- David Nasaw, The Last Million: Europe’s Displaced Persons from World War to Cold War (Penguin Press, 2020): “Much of what makes the book so absorbing and ultimately wrenching is his capacity to maneuver with skill between the nitty-grittiest of diplomatic (and congressional, military, personal) details and the so-called Big Picture. In cinematic terms, he’s adroit at surveying a vast landscape with a soaring crane shot, then zooming in sharply for a close-up of a single face as it crumples.”

Technical and Analytical Readings

Cultural perspectives:

- Guy Deutsche, Through the Language Glass: Why the World Looks Different in Other Languages (Metropolitan Books, 2010).

- Cordelia Fine, Delusions of Gender: How Our Minds, Society and Neurosexism Create Difference (W. W. Norton & Co., 2010).

Science: on the very large (cosmology) and the very small (particle physics):

- Dan Hooper, Particle Cosmology and Astrophysics (Princeton University Press, 2024).

- Lars Bergstrom & Ariel Goobar, Cosmology and Particle Astrophysics (Wiley, 1999).

Different perspectives in science:

- Tarja Knuuttila, Till Grüne-Yanoff, Rami Koskinen & Ylwa Sjölin Wirling, eds., Modeling the Possible: Perspectives from Philosophy of Science (Routledge, 2025).

- Jonah N. Schupbach & David H. Glass, eds., Conjunctive Explanations: The Nature, Epistemology, and Psychology of Explanatory Multiplicity (Routledge, 2024).

- Yafeng Shan, ed., New Philosophical Perspectives on Scientific Progress (Routledge, 2023).

- Sebastian Lutz & Adam Tamas Tuboly, eds., Logical Empiricism and the Physical Sciences: From Philosophy of Nature to Philosophy of Physics (Routledge, 2022).

Photographs

Documentary and Educational Films

Imaginary

Fictional Narratives

1831 and 1832, the two years which are immediately connected with the Revolution of July, form one of the most peculiar and striking moments of history. These two years rise like two mountains midway between those which precede and those which follow them. They have a revolutionary grandeur. Precipices are to be distinguished there. The social masses, the very assizes of civilization, the solid group of superposed and adhering interests, the century-old profiles of the ancient French formation, appear and disappear in them every instant, athwart the storm clouds of systems, of passions, and of theories. These appearances and disappearances have been designated as movement and resistance. At intervals, truth, that daylight of the human soul, can be descried shining there. [Victor Hugo, Les Misérables (1862), Volume IV – Saint-Denis; Book First – A Few Pages of History, Chapter I, “Well Cut”.]

Notre-Dame is not, moreover, what can be called a complete, definite, classified monument. It is no longer a Romanesque church; nor is it a Gothic church. This edifice is not a type. Notre-Dame de Paris has not, like the Abbey of Tournus, the grave and massive frame, the large and round vault, the glacial bareness, the majestic simplicity of the edifices which have the rounded arch for their progenitor. It is not, like the Cathedral of Bourges, the magnificent, light, multiform, tufted, bristling efflorescent product of the pointed arch. Impossible to class it in that ancient family of sombre, mysterious churches, low and crushed as it were by the round arch, almost Egyptian, with the exception of the ceiling; all hieroglyphics, all sacerdotal, all symbolical, more loaded in their ornaments, with lozenges and zigzags, than with flowers, with flowers than with animals, with animals than with men; the work of the architect less than of the bishop; first transformation of art, all impressed with theocratic and military discipline, taking root in the Lower Empire, and stopping with the time of William the Conqueror. Impossible to place our Cathedral in that other family of lofty, aerial churches, rich in painted windows and sculpture; pointed in form, bold in attitude; communal and _bourgeois_ as political symbols; free, capricious, lawless, as a work of art; second transformation of architecture, no longer hieroglyphic, immovable and sacerdotal, but artistic, progressive, and popular, which begins at the return from the crusades, and ends with Louis IX. Notre-Dame de Paris is not of pure Romanesque, like the first; nor of pure Arabian race, like the second. [Victor Hugo, Notre-Dame de Paris, or, The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1831), Volume I, Book Third, Chapter I, “Notre Dame”.]

Merlin the magician turns young Arthur in series into various animals, an experience that gives him the depth of experience to become a wise and just king.

- T.H. White, The Once and Future King (Putnam Adult, 1958).

Every work of fictional prose has a perspective but Robb Forman Dew' s novels, which follow "a formidably intermingled group of people in . . . Washburn, Ohio," are remarkable for the unique and often quirky perspectives of her characters.

- Robb Forman Dew, Being Polite to Hitler: A Novel (Little, Brown and Company, 2011).

- Robb Forman Dew, The Truth of the Matter: A Novel (Little, Brown and Company, 2005).

- Robb Forman Dew, The Evidence Against Her: A Novel (Little, Brown and Company, 2001).

- Robb Forman Dew, Fortunate Lives: A Novel (William Morrow, 1992).

- Robb Forman Dew, The Time of Her Life (William Morrow, 1984).

Other fictional treatments of perspective:

- Lydia Davis, Can’t and Won’t: Stories (Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2014): In these stories by a “patron saint of befuddled reality . . . . the common and the fathomless appear together on the same street.”

- Jenny Erpenbeck, Visitation: A Novel (Portobello, 2010): “ . . . tells, with impeccable delicacy and calm, the story of a lake house outside Berlin and its changing inhabitants over decades.”

- Anthony Doerr, Cloud Cuckoo Land: A Novel (Scribner, 2021): “Doerr hopes to give his readers perspective so they see their place on Earth, that “little mud-heap in a great vastness,” as a character in 'Cloud Cuckoo Land' calls it.”

Poetry

To see a World in a Grain of Sand / And a Heaven in a Wild Flower, / Hold Infinity in the palm of your hand / And Eternity in an hour.

[William Blake, from “Auguries of Innocence”.]

I believe a leaf of grass is no less than the journey work of the stars, / And the pismire is equally perfect, and a grain of sand, and the egg of the wren, / And the tree-toad is a chef-d'oeuvre for the highest, / And the running blackberry would adorn the parlors of heaven, / And the narrowest hinge in my hand puts to scorn all machinery, / And the cow crunching with depress'd head surpasses any statue, / And a mouse is miracle enough to stagger sextillions of infidels.

I find I incorporate gneiss, coal, long-threaded moss, fruits, grains, esculent roots, / And am stucco'd with quadrupeds and birds all over, / And have distanced what is behind me for good reasons, / But call any thing back again when I desire it.

In vain the speeding or shyness, / In vain the plutonic rocks send their old heat against my approach, / In vain the mastodon retreats beneath its own powder'd bones, / In vain objects stand leagues off and assume manifold shapes, / In vain the ocean settling in hollows and the great monsters lying low, / In vain the buzzard houses herself with the sky, / In vain the snake slides through the creepers and logs,

In vain the elk takes to the inner passes of the woods, / In vain the razor-bill'd auk sails far north to Labrador, / I follow quickly, I ascend to the nest in the fissure of the cliff.

[Walt Whitman, Leaves of Grass (1891-92), Book III: Song of Myself, 31.]

Other poems:

- Roald Dahl, “Hot and Cold”

Music: Composers, artists, and major works

The composer Alan Hovhaness once wrote: “I propose to create a heroic, monumental style of composition simple enough to inspire all people, completely free from fads, artificial mannerisms and false sophistications, direct, forceful, sincere, always original but never unnatural. Music must be freed from decadence and stagnation. There has been too much emphasis on small things while the great truths have been overlooked. The superficial must be dispensed with. Music must become virile to express big things. It is not my purpose to supply a few pseudo-intellectual musicians and critics with more food for brilliant argumentation, but rather to inspire all mankind with new heroism and spiritual nobility. This may appear to be sentimental and impossible to some, but it must be remembered that Palestrina, Handel and Beethoven would not consider it either sentimental or impossible. In fact, the worthiest creative art has been motivated consciously or unconsciously by the desire for the regeneration of mankind.” Few people would argue that Hovhaness stands among the pantheon of great composers. Yet his output was prolific, and in his compositions we see an attempt to present a musical world unbounded by parochial perspective. His music had a point of view to be sure but that point of view was as inclusive as he could make it. So while Mahler championed the idea that a symphony should be about everything, Hovhaness – a lesser composer than Mahler – freed himself compositionally from Mahler’s intensely personal perspective. His works are about grand ideas and draw on a broad spectrum of musical traditions. For those reasons, I offer Alan Hovhaness and his works to illustrate the virtue of perspective.

- Mysterious Mountain (approx. 19’)

- The Spirit of the Trees (1983) (approx. 23’)

- String Quartet No. 1, Op. 8 (1936) (approx. 13’)

- String Quartet No. 2, Op. 147 (1950) (approx. 5’)

- String Quartet No. 3, “Reflections on my Childhood”, Op. 208, No. 1 (1968) (approx. 15’)

- String Quartet No. 4, “Under the Ancient Maple Tree”, Op. 208, No. 2 (1970) (approx. 18’)

- Symphony No. 1, Op. 136, “Exile Symphony” (approx. 18’)

- Symphony No. 3, Op. 148 (1937) (approx. 28’)

- Symphony No. 4, Op. 176 (approx. 21’)

- Symphony No. 6, Op. 173, “Celestial Gate” (1959) (approx. 22’)

- Symphony No. 9, Op. 80, “St. Vartan” (1950) (approx. 41-49’)

- Symphony No. 16, Op. 202, “Korean Kayageum” (1962) (approx. 18’)

- Symphony No. 17, Op. 203, “Symphony for Metal Orchestra” (1963) (approx. 21’)

- Symphony No. 19, Op. 217, “Vishnu” (1966) (approx. 29’)

- Symphony No. 21, Op. 234, “Etchmiadzin” (1968) (approx. 17’)

- Symphony No. 22, Op. 236, “City of Light” (1970) (approx. 20-30’)

- Symphony No. 23, Op. 249, “Ani” (1972) (approx. 38’)

- Symphony No. 24, Op. 273, “Manjun” (1973) (approx. 48’)

- Symphony No. 25, “Odysseus Symphony” (1973) (approx. 41’)

- Symphony No. 26 in F minor, Op. 280 (1975) (approx. 40’)

- Symphony No. 29 for Baritone Horn and Orchestra, Op. 289 (1976) (approx. 25’)

- Symphony No. 31, Op. 294 (1976-1977) (approx. 22’)

- Symphony No. 34 for Bass Trombone and Strings, Op. 310 (1977) (approx. 24’)

- Symphony No. 39, Op. 321 (1978) (approx. 41’)

- Symphony No. 40 for Brass Quintet, Timpani and Strings, Op. 324 (1980) (approx. 20’)

- Symphony No. 43 for Oboe, Trumpet, Timpani and Strings, Op. 334 (1979) (approx. 23’)

- Symphony No. 47, “Walla Walla, Land of Many Waters” (1980) (approx. 50’)

- Symphony No. 48, Op. 355, “Vision of Andromeda” (1981) (approx. 30’)

Carl Nielsen, Symphony No. 5, Op. 50, FS 50, CNW 97 (1922) (approx. 35-40’): “Nielsen’s music, beginning with the Fourth Symphony, is full of conversations or confrontations, of the kind initiated here by the snare drum. These can be comic, or menacing (as they are here), or ambiguous.” “In form (the Fifth) is almost a cubist work, traditional symphonic movements skewed in irregular slabs within two movements which themselves form a sort of macro-movement. The harmonic underpinnings are also revealed in great faceted planes, rather than the traditions . . .” “When a reporter asked him on the day of the premiere about the subject or title of the work, Nielsen replied, 'It is nameless… The only thing that music can express when all is said and done: the resting powers as opposed to the active ones. If I were pressed to find a name for this, my fifth symphony, it would express something similar.'” Top recorded performances are conducted by Jensen in 1954, Bernstein in 1962 ***, Blomstedt in 1987, Colin Davis in 2009, Gilbert in 2014, and Luisi in 2022.

Other compositions:

- John Luther Adams, An Atlas of Deep Time (2024) (approx. 43’): “An Atlas of Deep Time lasts roughly 46 minutes, which equates to about 100 million years per minute. At that tempo, the entire history of the human family is represented in the dying reverberations of the last 25 milliseconds of this music.”

- Benjamin Frankel, Symphony No. 7, Op. 50 (1970) (approx. 31-35’), is about time. In the first movement, the composer ruminates, as an older man, about stopping time; in the second, he contemplates the sweep of time; in the third, he moves back and forth “between drama and nostalgia, between imminent threat and a dreamy closing of the eyes.” [the composer]

- Ben Johnston, String Quartet No. 4, “The Ascent – Amazing Grace” (1973) (approx. 11-12’), presents the traditional hymn in three forms of intonation.

- Heiner Goebbels, Suite for Sampler and Orchestra (1994) (approx. 31’): viewing a city from several levels and locations.

- Arthur Berger, Perspectives II (1985) (approx. 10’); Perspectives III (approx. 9’)

- Lewis Spratian, “Hesperus Is Phosphorous” (2012) (approx. 68’): “To the ancient Greeks, the morning and evening skies were home to two stars, Phosphorus at the beginning of the day and Hesperus at twilight. But the Babylonians knew what it took the Greeks centuries to discover: The morning and evening stars were one and the same -- the planet Venus, viewed through two different lenses, from two different perspectives.”

- John Luther Adams, Three High Places (2007, rev. 2017) (approx. 16’): “The album contains three pieces that capture the impressive grandeur of nature from the unconventional perspective of the double bass.”

Albums:

- Muhal Richard Abrams, “One Line, Two Views” (1994) (77’)

- Pharoah Sanders & The London Symphony Orchestra, “Floating Points” (2021) (47’)

Music: songs and other short pieces

- Bette Midler, “From a Distance” (lyrics)

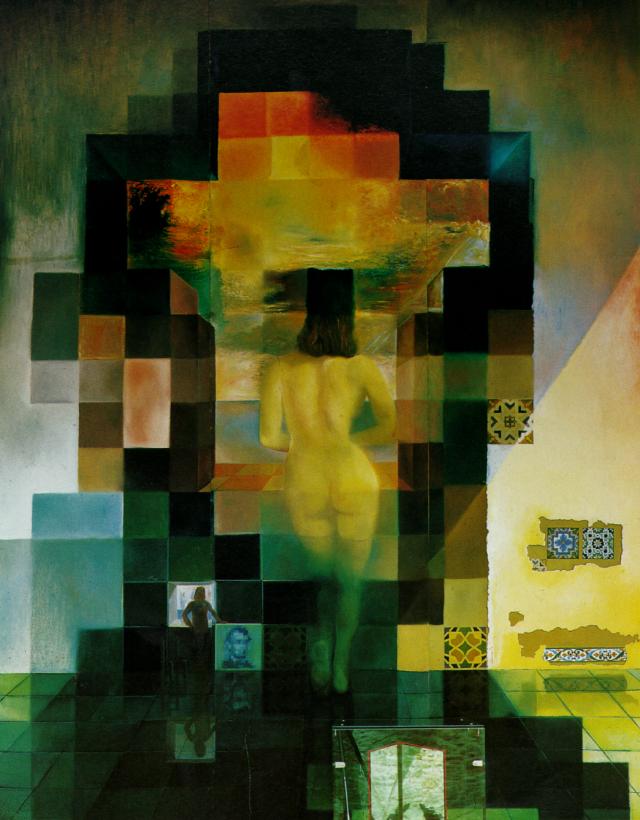

Visual Arts

- Canaletto, Grand Canal: Looking East from the Campo di San Vio (c. 1725)

- Canaletto, Grand Canal: Looking Northeast from the Palazzo Balbi to the Rialto Bridge (c. 1725)

- Canaletto, Entrance to the Grand Canal, Looking East (c. 1725)

- Canaletto, Grand Canal, Looking Southwest (1738)

Film and Stage

- Easy Living, a comedy illustrating the peculiarities of social favor