Tracking our progress helps us know whether we are on the right track, both in our choice of activities to pursue and in our progress within them. Sometimes the progress is transformative.

Real

True Narratives

We have reading lessons every day. Usually we take one of the little "Readers" up in a big tree near the house and spend an hour or two finding the words Helen already knows. We make a sort of game of it and try to see who can find the words most quickly, Helen with her fingers, or I with my eyes, and she learns as many new words as I can explain with the help of those she knows. When her fingers light upon words she knows, she fairly screams with pleasure and hugs and kisses me for joy, especially if she thinks she has me beaten. It would astonish you to see how many words she learns in an hour in the pleasant manner. Afterward I put the new words into little sentences in the frame, and sometimes it is possible to tell a little story about a bee or a cat or a little boy in this way. I can now tell her to go upstairs or down, out of doors or into the house, lock or unlock a door, take or bring objects, sit, stand, walk, run, lie, creep, roll, or climb. She is delighted with action-words; so it is no trouble at all to teach her verbs. She is always ready for a lesson, and the eagerness with which she absorbs ideas is very delightful. She is as triumphant over the conquest of a sentence as a general who has captured the enemy's stronghold. One of Helen's old habits, that is strongest and hardest to correct, is a tendency to break things. If she finds anything in her way, she flings it on the floor, no matter what it is: a glass, a pitcher or even a lamp. She has a great many dolls, and every one of them has been broken in a fit of temper or ennui. The other day a friend brought her a new doll from Memphis, and I thought I would see if I could make Helen understand that she must not break it. I made her go through the motion of knocking the doll's head on the table and spelled to her: "No, no, Helen is naughty. Teacher is sad," and let her feel the grieved expression on my face. Then I made her caress the doll and kiss the hurt spot and hold it gently in her arms, and I spelled to her, "Good Helen, teacher is happy," and let her feel the smile on my face. She went through these motions several times, mimicking every movement, then she stood very still for a moment with a troubled look on her face, which suddenly cleared, and she spelled, "Good Helen," and wreathed her face in a very large, artificial smile. Then she carried the doll upstairs and put it on the top shelf of the wardrobe, and she has not touched it since. [Annie Sullivan, Letters, May 22, 1887.]

Other narratives:

- Joyce West Stevens, Smart and Sassy: The Strengths of Inner-City Black Girls (Oxford University Press, 2002).

- Geoffrey Canada, Reaching Up for Manhood (Beacon Press, 1997).

- Paul Tough, Whatever It Takes: Geoffrey Canada's Quest to Change Harlem and America (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2008).

- Rebecca Carroll, Sugar in the Raw: Voices of Young Black Girls in America (Clarkson Potter, 1997).

- Emma Forrest, Your Voice in My Head: A Memoir (Other Press, 2011): a “protracted meditation on the blessing of self-transformation”.

- Mike Wallace, Greater Gotham: A History of New York City from 1898 to 1919 (Oxford University Press, 2017). “The 20 years that made New York City.”

- Zora Neale Hurston, Hitting a Straight Lick With a Crooked Stick: Stories from the Harlem Renaissance (Amistad/HarperCollins, 2020): “ Its 21 stories are presented in the order in which she composed them. As a result, readers can note the progression from earnest “apprentice” works and experiments with form to the polished brilliance of her best-known stories.”

- Celia Paul, Self-Portrait (New York Review Books, 2020): “. . . Paul’s account of her life and her work — or, more precisely, of her attempts to realize the possibilities of each despite the constraints thrown up by the other.”

- Glenn Adamson, Craft: An American History (Bloomsbury, 2021): “. . . Adamson manages to discover 'making' in every aspect of our history, framing it as integral to America’s idea of itself as a nation of self-sufficient individualists.”

Narratives of progress on a larger scale:

- Ira Rutkow, Empire of the Scalpel: The History of Surgery (Scribner, 2022): “. . . the emergence of surgery from its barbaric past rested on four pillars — the understanding of anatomy, the control of bleeding, anesthesia and antisepsis.”

Discovery:

- Edward J. Larson, An Empire of Ice: Scott, Shackleton, and the Heroic Age of Antarctic Science (Yale University Press, 2011).

Technical and Analytical Readings

- Joshua Foer, Moonwalking With Einstein: The Art and Science of Remembering Everything (The Penguin Press, 2011): the author practices and comments on developing memory.

- Bonnie J. Ross Leadbeater and Niobe Way, eds., Urban Girls: Resisting Stereotypes, Creating Identities (NYU Press, 1996).

- Bonnie J. Ross Leadbeater and Niobe Way, eds., Urban Girls Revisited: building strengths (NYU Press, 2007).

Photographs

Documentary and Educational Films

Imaginary

Fictional Narratives

Elif Batuman has begun a series of novels about a young woman, Selin, beginning with her freshman year at Harvard.

- The Idiot: A Novel (Penguin Press, 2017): “The Idiot may not have a point, or a definite meaning that can be extracted and spirited away like the prize in a cereal box, but it is full of subtle, playful insight on communication, language, and the painful process of choosing an identity without falling into scripted roles.”

- Either/Or: A Novel (Penguin Press, 2022): “an even better, more soulful novel (than The Idiot). Selin is more confident and, more important, so is Batuman.”

Other novels and stories:

- David Wiesner, Art & Max (Clarion Books, 2010). (See the author's recorded interviews on the Amazon site for the book.)

- Louise S. Rankin, Daughter of the Mountains (Puffin, 1993): “. . . after a band of robbers steals the valuable dog and quickly escapes with him into the mountains, Momo is determined to catch them and recover her beloved Pempa. To do so, she must follow the Great Trade Route across the mountains—a path that most people avoid, and which will surely put her life at risk. Momo undertakes a dangerous journey from the mountains of Tibet to the city of Calcutta, in search of her stolen dog Pempa.”

- Lauren Groff, Matrix: A Novel (Riverhead Books, 2021): “. . . it’s the dogged progress of a grand life that sustains this narrative. From its inauspicious beginning in the person of a sullen, selfish, godless teenager banished by an empress to perish in squalor, Marie’s transformation is that of a woman upon whom greatness is not thrust but slowly gathers.”

- Madeline L’Engle, The Moment of Tenderness: Stories (Grand Central, 2020): on L’Engle’s growth as a writer and her search for a personal philosophy.

Poetry

From the dark side:

- Edgar Lee Masters, “Abel Melveny”

Music: Composers, artists, and major works

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Symphony No. 25 in G Minor, K. 183/173dB (1773) (approx. 20-26’): “It is probably still a popular misconception that many of [Mozart's] great works date from early youth - but while it is true that there are flashes of inspiration in many of the early works, the first which has a firm footing in the modern repertoire is the… G-minor Symphony, K. 183, written when he was seventeen.” It “is considered to be Mozart’s first ‘tragic’ symphony and was written in the Sturm und Drang style. The Sturm und Drang (Storm and Stress) movement in music featured dramatic emotional extremes often represented by minor keys as in this symphony, and by dramatic and sudden changes in tempo, dynamics, expressive music elements, and with effects such as the use of tremolo.” “Many critics regard this as one of the moments when Mozart transformed from entertainer to artist – from wunderkind to great composer.” Top recorded performances are conducted by Walter in 1955, Britten in 1971, Marriner in 1974, Bernstein in 1988, Mackerras in 1988, Tate in 1990, Pinnock in 1994, Adam Fischer in 2009, and Wåhlberg in 2021.

Mozart’s Symphony No. 41 in C Major, K. 551, “Jupiter” (1788) (approx. 30-41’): Mozart could not have known that his 41st symphony would be his last but it can be heard as the pinnacle of his career as a composer. He did not name this symphony after the supreme Roman god. A noted composer and publisher of the time revealed: “Mozart’s son said he considered the Finale to his father’s Sinfonia in C—which Salomon christened the Jupiter—to be the highest triumph of Instrumental Composition, and I agree with him.” The work is “known for its good humour, exuberant energy, and unusually grand scale for a symphony of the Classical period.” “Although the reference to an Olympian god was not the composer's choice, he did signal clearly with his _musical _choices that he meant the work as a bold statement.” Great recorded performances are conducted by Strauss in 1926, Szell in 1955 **, Beecham in 1957 **, Klemperer in 1962 **, Colin Davis in 1982, Kubelik in 1985, Iván Fischer in 1988, Abbado in 2008, Mackerras in 2008 ***, Gardiner in 2011 **; and Herzog in 2018.

Both in his development of the art form of piano sonata and in his characteristically positive compositional attitude, Franz Joseph Haydn demonstrates the virtue and desideratum of progress. Beginning with the early sonatas (listen to the first dozen or so, on recordings by John McCabe, Rudolf Buchbinder, Walid Akl, and various artists) and working toward the later ones (listen to later sonatas on recordings by McCabe, Buchbinder, Akl, various artists, and Glenn Gould), listen to the musical development as this great composer immersed himself in this genre. (Because I have chosen Haydn’s middle period piano sonatas to illustrate the virtue of groundedness, the focus here is on his earliest and latest sonatas.) Fittingly, Haydn composed these works for amateur performers, thereby adding to them an element of charm.

Ludwig van Beethoven’s Op. 10 piano sonatas are at a higher level than Haydn’s, both in complexity and in difficulty, but for Beethoven, they represent advancement in his development as a composer.

- Piano Sonata No. 5 in C minor, Op. 10/1 (1798) (approx. 16-21’) “is Beethoven’s first published piano sonata to have only three movements instead of four. Beethoven wrote the first four sonatas to sound like symphonies . . .”

- Piano Sonata No. 6 in F major, Op. 10/2 (1798) (approx. 13-17’): “. . . in this sonata, we have two themes, ‘something vertical against something horizontal,’ as Schiff says.”

- Piano Sonata No. 7 in D major, Op. 10/3 (1798) (approx. 22-25’): “Angela Hewitt . . . calls this work 'the first masterpiece in the cycle of sonatas,' and Schiff calls it 'one of the miracles of music, not just of Beethoven.'”

Philip Glass, Études (2012) (approx. 143-146’): “Begun to improve his own technique, piano exercises that Glass wrote over decades” these minimalist works evoke the theme of making progress personally. “His most personal body of work, the pieces are a self-portrait of a life’s practice, representing some of the most intimate and inventive music of Glass’s oeuvre.” Top performances are by Anton Batagov in 2017 (Book 1; Book 2); Maki Namekawa in 2014; Víkingur Ólafsson in 2016 (13 of 20 Études); and Jeroen van Veen in 2017.

Composer Richard Hol did an excellent job developing the themes in these symphonies:

- Symphony No. 1 in C minor (1863) (approx. 24’) “begins with a slow introduction leading to a Schumanesque allegro with a very catchy second subject melody. The slow movement’s theme is beguiling as well and is reminiscent of the Offenbach of Gaité Parisienne. A ‘hunting’ scherzo in the style of Berlioz forms the third movement, and the symphony ends with a tarantella that reprises the second movement’s theme.”

- Symphony No. 2 in D minor, Op. 44 (1866) (approx. 34-36’)

- Symphony No. 3 in B-flat major, Op. 101 (1867/1884) (approx. 31’): “Its outstanding features are the scherzo, subtitled ‘Erinnerung an Mendelssohn’, and the Nachtmusik, a Schubert-like andante with two scherzo episodes.”

- Symphony No. 4 in A major (1889) (approx. 30’)

You can hear these composers develop their skills over the course of their careers:

- John Abraham Fisher, Symphonies 1-6 (late 1700s) (approx. 57’)

George Frideric Händel’s organ concerti (approx. 260-265’) suggest progress and accomplishment within each concerto:

- Organ Concerti, Op. 4 (1735-1736) (approx. 70’): No. 1 in G minor – G major, HWV 289 (approx. 16’); No. 2 in B-flat major, HWV 290 (approx. 10’); No. 3 in G minor, HWV 291 (approx. 10’); No. 4 in F major, HWV 292 (approx. 13’); No. 5 in F major, HWV 293 (approx. 9’); No. 6 in B-flat major, HWV 294 (approx. 12-13’).

- Organ Concerti, Op. 7 (1740-1751) (approx. 53-68’): No. 1 in B flat major, HWV 306 (approx. 15-16’); No. 2 in A major, HWV 307 (approx. ); No. 3 in B flat major, HWV 308 (approx. 14’); No. 4 in D minor, HWV 309 (approx. 13-16’); No. 5 in G minor, HWV 310 (approx. 13’); No. 6 in B-flat Major, HWV 311 (approx. 8-9’).

- Organ Concerto No. 13 in F major, HWV 295, “The Cuckoo and the Nightingale” (1739) (approx. 12-15’)

- Organ Concerto No. 14 in A major, HWV 296a (approx. 17-18’)

- Organ Concerto No. 15 in D minor, HWV 297 (ca. 1740) (approx. 20’)

- Organ Concerto No. 16 in G major, HWV 298 (ca. 1740)

- Organ Concerto No. 17 in D major, HWV 299 (ca. 1740)

- Organ Concerto No, 18 in G minor, HWV 300 (ca. 1740)

- Organ Concerto in D minor, HWV 304 (1746’) (approx. 12’)

Other works:

- Gian Carlo Menotti, Ahmal and the Night Visitors (1951) (approx. 59’) is a story about a boy growing up, a bit.

- Antonín Dvořák, Symphony No. 5 in F Major, Op. 76, B. 54 (1875, rev. 1887) (approx. 37-40’) (top recordings review) “demonstrates a significant improvement in his endeavour to grasp the formal arrangement of the individual movements, and his ability to articulate the thematic material within them.”

- Dvořák, Symphony No. 6 in D Major, Op. 60, B. 112 (1880) (approx. 42-45’) (top recordings review): “By the mid-1870s, all of the elements that form the mature Dvorák began taking proper shape and perspective . . . The Sixth Symphony was the harbinger of the composer's maturity.”

- Camille Saint-Saëns composed his Symphony in F Major, “Urbs Roma” (1856) (approx. 41-42’), for a competition when he was fifteen years old.

- Laura Netzel, Piano Concerto in E Minor, Op. 84 (ca. 1897) (approx. 25-28’): “Laura Netzel broke new ground with the piano concerto, both for herself and for female composers in Sweden.” The work is in a standard fast-slow-fast sequence, and drives toward an emphatic conclusion.

- Hélène de Montgeroult, complete piano sonatas (1820s-1830s) (approx. 165’): “. . . Montgeroult’s music sounds very much like what you’d expect to hear from a virtuoso pianist-composer writing around the transition into the 19th century, one who studied with Clementi and Dussek and whose aesthetic outlook (especially in harmonic practice) straddled the line between Classicism and Romanticism. . . Listen a little more closely, and you find that she’s a composer who loves to subvert . . . expectations . . .”

- Charles Hubert Hastings Parry, Charakterbilder, “Seven Ages of Mind” (1872) (approx. 25’)

- George Lloyd, Symphony No. 11 (1985) (approx. 59’); and Lloyd, Symphony No. 12 (1989) (approx. 41’): “Both are big statements, and in them the composer appears to have left anguish behind. Instead, he concentrates on the process of symphonic development.”

Albums:

- Michel Petrucciani, Gary Peacock and Roy Haynes, “One Night in Karlsruhe” (2019) (68’)

- Ivo Perelman & Matthew Shipp, “Efflorescence, Volume 1” (2019) (211’)

- Steven Beck, “George Walker: Five Piano Sonatas (1953-2003)”: the advances in Walker’s compositional skills over time are apparent.

- Julia Hülsmann Quartet, “The Next Door” (2022) (60’): “Julia Hülsmann returns with the quartet from 2019’s Not Far From Here, and presents her unique pianistic voice in a varied programme of almost exclusively original music, composed by herself and her colleagues – tenor saxophonist Uli Kempendorff, Marc Muellbauer on double bass and drummer Heinrich Köbberling. A deep respect for the jazz tradition, as cultivated in the post-bop and modal jazz of the 60s, permeates this session and, with the quartet’s modern twist, sets the stage for highly expressive soloing and profound interplay.”

- Opus 5, “Progression” (2014) (62’): “A collaborative ensemble, each member of Opus 5 contributes an arrangement here which helps raise the bar from a simple blowing session to a distinct, group-oriented aesthetic, which is not to say there isn't a fair share of harmonically advanced, intensely swinging playing on display.”

- Mikhail Korzhev, “Early Piano Works of Ernest Krenek” (2023) (67’): the works “demonstrate a transition toward maturity along multiple and sometimes circuitous paths.” Compare and contrast that album with Korzhev’s album of Krenek’s later works, including two piano sonatas (2008) (76’).

- Magnus Öström & Dan Berglund, “e.s.t. 30” (2024) (47’): “The iconic melodies and rhythms are all there, but we also hear how they are opened up again and again, as the musicians immerse them in unexpected warmth and light. These players react to each other in fascinating ways, and there is also a definite tingle in the air as the audience listens to the music in pin-drop silence, then bursts into uninhibited applause at the end.”

Music: songs and other short pieces

- Survivor, “Eye of the Tiger” (lyrics)

- Franz Schubert (composer), An Mein Klavier (To My Piano), D. 342 (1816) (lyrics)

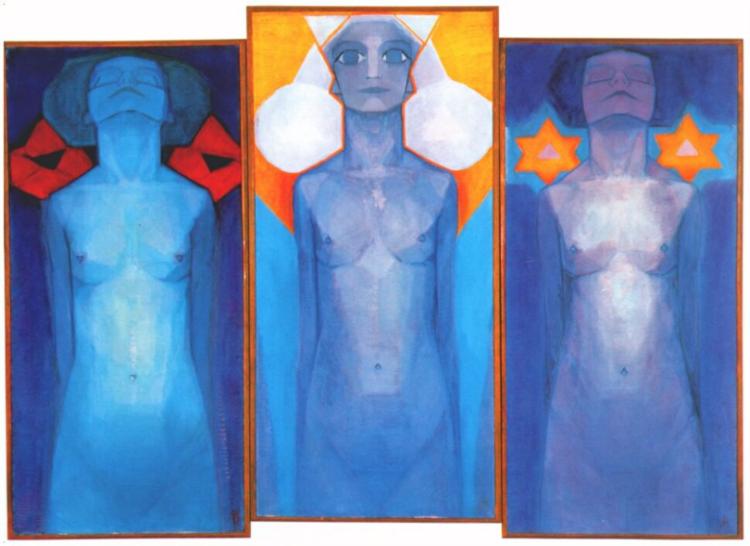

Visual Arts

- Lee Krasner, Rising Green (1972)

- Joan Miró, The Two Philosophers (1936)

- Joan Miró, Metamorphose (1936)

- Wassily Kandinsky, Gentle Ascent (1934)

- Paul Klee, Ad Parnassum (1932)

- Paul Klee, Conqueror (1930)

- Paul Klee, Hamamet (1914)

- Edgar Degas, Danseuse

- Ivan Aivazovsky, The Coast at Amalfi (1841)

- Bernardo Bellotto, Arno in Florence (early 1740s)

Film and Stage

- American Movie, about a man with aspirations to make a film and his labors

- Empire of the Sun, about a boy’s transformation from a spoiled child of privilege to an emerging teenager ready to face life with dignity

- Il Generale della Rovere (General Della Rovere): a “study of a man's transformation during the German occupation of Milan”