Commitment fidelity is more than merely keeping promises. It is a core commitment, religious in nature.

- Many persons have a wrong idea of what constitutes true happiness. It is not attained through self-gratification but through fidelity to a worthy purpose. [Helen Keller]

- There are thousands who are in opinion opposed to slavery and to the war, who yet in effect do nothing to put an end to them; who, esteeming themselves children of Washington and Franklin, sit down with their hands in their pockets, and say that they know not what to do, and do nothing. [Henry David Thoreau, “On the Duty of Civil Disobedience”]

Fidelity to a commitment to the highest good is the pinnacle of human ethical development. When a person’s entire being is devoted to the most worthy ideal to which that person can aspire, the ethical journey has reached its final plateau. We see this not as arrival at a final destination because the point and purpose of reaching this lofty state of Being is to serve the good. We have “miles to go before (we) sleep“, and worlds of work to do.

Real

True Narratives

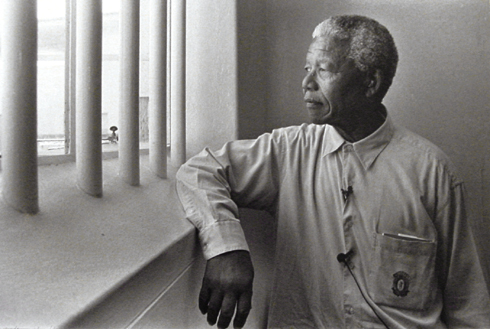

In his public life as an activist, Nelson Mandela exemplifies the virtue of commitment fidelity. Though imprisoned for twenty-seven years, he remained true to his commitment to justice for the black South African people.

- Nelson Mandela, Long Walk to Freedom: The Autobiography of Nelson Mandela (Holt, Rinehart & Winston, 2000).

- Nelson Mandela, Conversations with Myself (Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2010).

- Nelson Mandela, Mandela: An Illustrated Autobiography (Little, Brown & Company, 1996).

- Tom Lodge, Mandela: A Critical Life (Oxford University Press, 2006).

- Richard Stengel, Mandela's Way: Fifteen Lessons on Life, Love, and Courage (Crown Archetype, 2010).

- John Carlin, Playing the Enemy: Nelson Mandela and the Game that Made a Nation (Penguin Press, 2008).

- Gabriel García Márquez, The Scandal of the Century and Other Writings (Knopf, 2019): “A resonant new collection of García Márquez’s journalism, ‘The Scandal of the Century,’ demonstrates how seriously he took reportage and what’s now sometimes called (would Liebling approve?) long-form narrative.”

Commitment fidelity on a large scale:

- Gary W. Gallagher, The Union War (Harvard University Press, 2011): presenting the Civil War as a commitment by the North to transforming “a government ‘for white men’ into one ‘for mankind.’”

- Janice P. Nimura, The Doctors Blackwell: How Two Pioneering Sisters Brought Medicine to Woman – and Women to Medicine (W.W. Norton & Company, 2021): “Elizabeth, especially, would rhapsodize about humanity in the abstract, even as actual experiences of clinical intimacy could unnerve her. ‘I feel neither love nor pity for men, for individuals,’ she declared as a young doctor, in a letter to one of her brothers. ‘But I have boundless love & faith in Man, and will work for the race day and night.'”

Technical and Analytical Readings

Photographs

Documentary and Educational Films

Imaginary

Fictional Narratives

Novels:

- Megan Abbott, You Will Know Me: A Novel (Little, Brown & Company, 2016): “At first Katie appears frustrated by the lack of honest communication, but when she finally gets the chance to do something about it, she opts instead to fall in with the evasiveness that’s all around her. The reader is left feeling silly for expecting this manifestly flawed woman to be suddenly heroic. Real life, expertly mimicked by this excellent novel, simply doesn’t work that way.” (walking the talk)

- Kevin Nguyen, Mỹ Documents: A Novel (One World, 2025): “The land of the free is also the land of the incarcerated, the detained, the interned. In that sense, Kevin Nguyen has written a very American novel indeed.”

Poetry

Poems:

- Robert William Service, “The Cremation of Sam McGee”

Music: Composers, artists, and major works

Myra Hess was a classical pianist with a deep commitment to the composer’s intentions. Here is a link to some of her output.

In the times of Beethoven and Mozart, people commonly saw devotion and fidelity to God as the greatest commitment of all. Yet Beethoven was an infrequent churchgoer and Mozart's playful irreverence was legendary. Formally, their compositions and especially their lyrics reflected their churches but their music voices a more universal idea. We can hear the idea of commitment fidelity expressed in their two most reverential works, both for chorus and orchestra. Though Beethoven was careful to compose his Missa solemnis in the style of the Church, most experts believe that his composition of this work reflected a conviction that our deeper obligation was to each other. Beethoven's Ninth Symphony, Op. 125 and composed in 1824, would celebrate human joy and freedom. We can hear the progression toward a more explicit Humanism by listening carefully to these two works.

- Ludwig van Beethoven, Missa solemnis in D major, Op. 123 (1823) (list of recorded performances): “Beethoven invested much of himself in the Missa Solemnis. As preparation, he immersed himself in an intensive study of religious music of the past, from monastic chants to Handel’s Messiah (he incorporated the melody of ‘And He Shall Reign’ into his Dona nobis pacem) and the Mozart Requiem, portions of which he copied out.” “Because the work had come to mean so much to him during the years that he was working on it, he set great store on its presentation to the public in print and in performance. Beethoven engaged in a vast correspondence with publishers, crowned heads and their representatives, and patrons of various kinds, in order to ensure a worthy destiny for his Grand Mass.” “In a letter written in 1824, Beethoven wrote, 'my chief aim [in writing the Missa Solemnis] was to awaken and permanently instill religious feelings not only into the singers but also into the listeners.'” Great performances are by: Baillie, Jarred, Nash & Falkner (Beecham) in 1937; Milanov, Castagna, Björling & Kipnis (Toscanini) in 1940; Söderström, Höffgen, Kmentt & Talvela (Klemperer) in 1965; Janowitz, Ludwig, Wunderlick & Berry (Karajan) in 1966; Janowitz, Baltsa, Schreier & van Dam (Karajan) in 1975; Cuberli, Schmidt & Cole (Karajan) in 1985; McNair, Aler, Taylor & Krause (Shaw) in 1988; Margiono, Robbin, Kendall & Miles (Gardiner) in 1989; Illing, Campbell, Doig & McCann (Marriner) in 1992; Mannion, Remmert, Taylor, & Hauptmann (Herreweghe) in 1995; Davies, Lippert, Ziesak & Fink (Harnoncourt) in 1998; Alkin, Kulman, Chum & Drole (Harnoncourt) in 2015; Winkel, Harmsen, Kohlhepp & Kataja (Bernius) in 2018; and Reiss, Abrahamyan, Behle & Nazmi (Rhorer) in 2025.

- Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Mass in C minor, K. 427 (1783) (approx. 53-57’) (list of recorded performances). Mozart wrote to his father on January 4, 1783: “It is quite true about my moral obligation... I made the promise and hope to be able to keep it . . . When I made it, my wife was still single; yet as I was determined to marry her soon after her recovery . . . it was easy for me to make it - but as you yourself are aware, time and other circumstances made our journey impossible. The score of half a mass which is still lying here waiting to be finished, is the best proof that I really made the promise . . .” Great performances are by: Stader & Töpper (Fricsay) in 1959; Donath & Harper (Colin Davis) in 1971; McNair & Montague (Gardiner) in 1986; Auger & Dawson (Hogwood) in 1988; Hendricks & Coburn (Schreier) in 1988-89; Augér & von Stade (Bernstein) in 1990; Piau & Sollied (Krivine) in 2006; Dessay & Gens (Langrée) in 2006 ***; Persson & Hallenberg (Gardiner) in 2008; and Sampson & Vermeulen (Suzuki) in 2016.

Ernest Bloch’s chamber works exude a seriousness of purpose, evoking this value.

- String Quartet in G Major (1896) (approx. 31’)

- String Quartet No. 1 (1916) (approx. 59’)

- String Quartet No. 2 (1945) (approx. 34’) (list of recorded performances)

- String Quartet No. 3 (1952) (approx. 26’)

- String Quartet No. 4 (1953) (approx. 30’)

- Piano Quintet No. 1 (1923) (approx. 32-34’) (list of recorded performances)

- Piano Quintet No. 2 (1957) (approx. 18’) (list of recorded performances)

- Cello Suite No. 1 (1956) (approx. 10-11’) (list of recorded performances)

- Cello Suite No. 2 (1957) (approx. 19’) (list of recorded performances)

- Cello Suite No. 3 (1957) (approx. 12’) (list of recorded performances)

- (all three cello suites)

- Suite Hébraique for violin and piano (1951) (approx. 15’) (list of recorded performances)

- Suite No. 1 for solo violin (1958) (approx. 10-11’) (list of recorded performances)

- Suite No. 2 for solo violin (1958) (approx. 11-12’) (list of recorded performances)

- Suite for viola and piano (1919) (approx. 31’) (list of recorded performances)

- Baal Shem (Three Pictures of Chassidic Life) for violin and piano, or violin and orchestra (1932) (approx. 14-15’) (list of recorded performances)

Other works:

- Johannes Brahms, 4 Ballades, Op. 10 (1854) (approx. 24-26’) (list of recorded performances): “Besides the consistent use of ternary form, Brahms also constructed his ballades to stand as a unified set. On first glance, it is noticed that they are arranged into complementary minor/major pairs: the first two in D minor and D major, respectively, and the second, likewise, in B minor and B major. Even within the set as a whole, the principal keys used throughout center consistently around the tonics of D, B, and F-sharp.”

- Nicolas Flagello, Piano Concerto No. 1 (1950) (approx. 29’) “shows the influence of Rachmaninoff, especially in the sprawling first movement. Oddly, the piano's dramatic entry recalls the opening of the MacDowell First, probably more a coincidence since little else in the work divulges anything related to the music of that American composer. There are also hints of Bartók here too, especially from the Third Piano Concerto, which was a new work at the time Flagello was composing this concerto.”

- Richard Arnell, Symphony No. 7, Op. 201, “Mandela” (1996) (approx. 37’)

- Arnold. Bax, Piano Sonata No. 1 in F-sharp Minor (1910) (approx. 18-23’) (list of recorded performances): “As a technical exercise one could wish for nothing more exacting than the ‘Romantic Tone-Poem’ … the composer presumably had some ‘programme’ in his mind when he wrote it, but since so clue was afforded of its meaning, the audience was left to imagine the romance that had inspired music so rhetorical as this proved to be.”

- Charles-Marie Widor, Symphony No. 6 in G Minor, Op. 42/2 (1878) (approx. 35-36’) (list of recorded performances): “Widor cast his Sixth Symphony in a grand, five-movement arch - three bravura demonstrations in the tonic key separated by two tonally remote, lyrical introspections.”

- Pyotr Iylich Tchaikovsky, Grande Sonata in G Major, Op. 37 (1878) (approx. 31-35’) (list of recorded performances): “The second movement Andante is the emotional core of the Sonata. A succession of nocturne-like themes achieves a sorrowful mood akin to Chopin or Tchaikovsky's admired Schumann. It is difficult here, as it is with the Dumka, to resist attaching biographical significance to the music, but in contrast to the later work, a certain air of serenity and play never allows the music to retreat into bleakness.”

- Henrique Oswald, Piano Concerto in G Minor, Op. 10 (1886) (approx. 30’): “The composer had met Liszt at about the time of composition and this, in some respects, translates into the virtuosic writing found in the score. After the sweeping gestures of the opener, the second movement is the emotional heart of this prepossessing score, exquisitely drafted and bathed in unalloyed lyricism. The manic finale combines good humour, glee with some Litolff Scherzo and a hint of Saint-Saëns for good measure.”

- Kalevi Aho, Concerto for Percussion and Orchestra, “Sieidi” (2010) (approx. 32-36’): “For the soloist it is extremely demanding because he is constantly having to switch from one technique to another – for djembe and darabuka playing with the hands differs radically from that of tom-tom or drumstick technique or the playing of pitched percussion instruments such as the marimba and vibraphone.”

- César Franck, Piano Trio in F-sharp Minor, Op. 1, No. 1, CFF 111 (1842) (approx. 30-35’) (list of recorded performances): “With its budding genius, this trio marks an epoch in the history of musical evolution . . . alone at this period, the young composer ventured to plan his first important work according to ideas which Beethoven did little more than touch on in the last years of his life.”

Music: songs and other short pieces

- “We Shall Not Be Moved”: The Freedom Singers at the March on Washington, August 28, 1963; Pete Seeger (lyrics), The Seekers

- “I Shall Not Be Moved”: Rhiannon Giddens, Mississippi John Hurt

- Matt Greenwood, “Commitment”

Visual Arts

Film and Stage

- Brief Encounter, in which two people are tested in their commitment to marriage

- Ratatouille, an animated feature about a rat with extraordinary culinary talents who must decide where he best fits in, the film reminds us that “a great artist can come from anywhere” – well, almost.