Great accomplishments begin with ideas, and visions of how things might be.

- Everything begins with an idea. [attributed to Earl Nightingale]

- The best way to have a good idea is to have a lot of ideas. [Linus Pauling]

- Great minds discuss ideas; average minds discuss events; small minds discuss people. [in content, Henry Thomas Buckle]

Every purposeful action begins with an idea. Architects, composers, authors, farmers, coaches, all begin their work with an idea. The history of ideas is rich. In fact, most of our history, in a way, is a history of ideas.

Equally or more important, evolution drives every dynamic system. People are most familiar with biological evolution but human practices and institutions evolve too. That evolution is driven by ideas. The idea is to social evolution as the gene is to biological evolution.

An idea may be simplistic, or it may be transcendent. “. . . six categories of individual-level factors . . . have been found to promote the successful implementation of innovations: expertise, motivation, cognitive factors, personality traits, attitudes and social skills”.

The means by which ideas penetrate into and change a discipline or field of endeavor is a subject of scrutiny.

- “. . . new ideas diffuse more widely when they socially and intellectually resonate. New ideas become core concepts of science when they reach expansive networks of unrelated authors, achieve consistent intellectual usage, are associated with other prominent ideas, and fit with extant research traditions.”

- “Based on ideation practices of sophisticated companies, this paper triggers academic researchers to self-reflect on: (1) the source used for ideation, (2) the scope applied to ideation, (3) the sharing of ideas during ideation, and (4) the selection of ideas.”

Age and experience of idea generators appears to follow unsurprising patterns. “. . . papers published in biomedicine by younger researchers are more likely to build on new ideas. Collaboration with an experienced researcher matters as well. Papers with a young first author and a more experienced last author are more likely to try out newer ideas than papers published by other team configurations.” “. . . interdisciplinary scientists who completed two or more degrees in different academic fields by the time of discovery made about half—54%—of all nobel-prize discoveries and 42% of major non-nobel-prize discoveries over the same period; this enables greater interdisciplinary methodological training for making new scientific achievements. Science is also becoming increasingly elitist, with scientists at the top 25 ranked universities accounting for 30% of both all nobel-prize and non-nobel-prize discoveries. Scientists over the age of 50 made only 7% of all nobel-prize discoveries and 15% of non-nobel-prize discoveries and those over the age of 60 made only 1% and 3%, respectively.”

Great ideas have changed disciplines, and the world.

- “On rare occasions in the history of science, remarkable discoveries transform human society and forever alter mankind’s view of the world. Examples of such discoveries include the heliocentric theory, Newtonian physics, the germ theory of disease, quantum theory, plate tectonics and the discovery that DNA carries genetic information.”

- In mathematics, “the creative unit is not the novel or symphony, but the theorem.” Not exclusively, though: “Our modern system of positional decimal arithmetic with zero,which was discovered in India in the fourth or fifth century.”

- “Anthropogenic impacts increasingly drive ecological and evolutionary processes at many spatio-temporal scales, demanding greater capacity to predict and manage their consequences. This is particularly true for agro-ecosystems, which not only comprise a significant proportion of land use, but which also involve conflicting imperatives to expand or intensify production while simultaneously reducing environmental impacts.”

- “The relevance of ideas is at the core of the (international business field and has been captured in concepts like technology, innovation and knowledge.”

- “Policy making in health is largely thought to be driven by three ‘I’s namely ideas, interests and institutions.”

- The Répertoire International de Littérature Musicale has published a lengthy treatise on music history.

- “From the Renaissance’s exploration of the human form to Abstract Expressionism’s exploration of the subconscious, each period in art history has created a unique and influential mark on the art world.”

- “. . . the culinary arts have undergone a remarkable transformation over the centuries, evolving from traditional techniques steeped in culture and heritage to the innovative practices of modernist cuisine. Traditional culinary methods, rooted in time-honoured recipes and regional ingredients, emphasize a deep connection to local cultures and the art of handcrafting meals. Techniques such as fermentation, smoking, and slow cooking were honed by generations, celebrating the natural Flavors and textures of ingredients.”

- “Some historical examples of the evolution to which sport scientists have contributed were the change in swimsuit material from cotton to today’s synthetic materials, the changes in bicycle geometry to improve the cycling performance, and the transition from ashy athletics tracks to the current tartan, which continues to improve with every international competition.”

Real

True Narratives

- Scott L. Montgomery & Daniel Chirot, The Shape of the New: Four Big Ideas and How They Made the Modern World (Princeton University Press, 2015): “The authors’ big four are Adam Smith, Karl Marx, Charles Darwin and (a joint prize) Thomas Jefferson and Alexander Hamilton. The ideas are, of course, capitalism, socialism, evolution and liberal democracy.”

- Peter Watson, Ideas: A History of Thought and Invention, from Fire to Freud (Harper, 2005).

- Peter Watson, The German Genius: Europe's Third Renaissance, the Second Scientific Revolution, and the Twentieth Century (Harper, 2010).

- Peter Watson, The Modern Mind: An Intellectual History of the Twentieth Century (HarperCollins 2001).

- Isaiah Berlin, The Power of Ideas (Princeton University Press, 2000).

- Isaiah Berlin, Political Ideas in the Romantic Age: Their Rise and Influence on Modern Thought (Chatto and Windus, 2006).

- Samuel Moyn & Andrew Sartori, eds., Global Intellectual History (Columbia University Press, 2013).

- Frank M. Turner, European Intellectual History from Rousseau to Nietzsche (Yale University Press, 2014).

- Linda Trinkaus Zagzebski, The Two Greatest Ideas: How Our Grasp of the Universe and Our Minds Changed Everything (Princeton University Press, 2021).

- Pierre Manent, An Intellectual History of Liberalism (Princeton University Press, 1995).

- Geoffrey J. Martin, All Possible Worlds: A History of Geographical Ideas (Oxford University Press, 2005).

- Mark Blyth, Great Transformations: Economic Ideas and Institutional Change in the Twentieth Century (Cambridge University Press, 2002).

- Mark Bevir, The Logic of the History of Ideas (Cambridge University Press, 1999).

- Nancy Folbre, Greed, Lust & Gender: A History of Economic Ideas (Oxford University Press, 2010).

- Donald R. Kelley, The Descent of Ideas: The History of Intellectual History (Ashgate, 2002).

- Daniel Dennett, Darwin's Dangerous Idea: Evolution and the Meanings of Life (Simon & Schuster, 1995).

- Michael Ruse, ed., Philosophy After Darwin: Classic and Contemporary Readings (Princeton University Press, 2009).

- Daniel N. Robinson, An Intellectual History of Psychology (University of Wisconsin Press, 1976).

- Franklin Le Van Baumer, Main Currents of Western Thought: Readings in Western European Intellectual History from the Middle Ages to the Present (Yale University Press, 1978).

- Charles van Doren, A History of Knowledge: Past, Present, and Future (Citadel, 1991).

- Jacob Bronowski and Bruce Mazlish, The Western Intellectual Tradition: From Leonardo to Hegel (Marboro Books, 1986).

- Steven Ozment, The Age of Reform, 1250-1550: An Intellectual History of Late Medieval and Reformation Europe (Yale University Press, 1981).

- John Herman Randall, Jr., The Making of the Modern Mind A Survey of the Intellectual Background of the Present Age (1926).

- Merle Goldman and Leo Ou-Fan Lee, eds., An Intellectual History of Modern China (Columbia University Press, 2002).

- Sheldon Pollock, ed., Forms of Knowledge in Early Modern Asia: Explorations in the Intellectual History of India and Tibet, 1500-1800 (Duke University Press Books, 2011).

- Andrew J. Nicholson, Unifying Hinduism: Philosophy and Identity in Indian Intellectual History (Columbia University Press, 2010).

- Shabnum Tejani, Indian Secularism: A Social and Intellectual History, 1890-1950 (Indiana University Press, 2008).

- Marcia L. Colish, Medieval Foundations of the Western Intellectual Tradition (Yale University Press, 1997).

- Richard Tarnas, The Passion of the Western Mind: Understanding the Ideas That Have Shaped Our World View (Ballantine Books, 1993).

- T.Z. Lavine, From Socrates to Sartre: The Philosophic Quest (Bantam Books, 1985).

- Mortimer J. Adler, How to Think About the Great Ideas: From the Great Books of Western Civilization (Open Court, 2000).

- Scott O. Lilenfeld and William T. O'Donohue, eds., The Great Ideas of Clinical Science: 17 Principles That Every Mental Health Professional Should Understand (Routledge, 2006).

- George Dyson, Turing’s Cathedral: The Origins of the Digital Universe (Pantheon Books, 2012): about John von Neumann, “who invented almost nothing, yet whose vision changed the world”, and others who midwifed the computer age.

- Randall Fuller, The Book That Changed America: How Darwin’s Theory of Evolution Ignited a Nation (Viking, 2017): “His account of how Americans responded to the publication of Darwin’s great work in 1859 is organized as a series of lively and informative set pieces — dinners, conversations, lectures — with reactions to ‘On the Origin of Species’ usually (but not always) at the center.”

- Gordon S. Wood, The Idea of America: Reflections on the Birth of the United States (Penguin Press, 2011): Wood “went deep into primary materials and made an open-minded effort to understand the language and thought of 18th-century Americans in their own terms.”

- Julia Lovell, Maoism: A Global History (Knopf, 2019): “. . . Maoism was more than an amorphous idea, but a strategy pushed by China. It trained revolutionary leaders inside China, sent advisers abroad and delivered material support, from weapons to the black pajama-type uniforms of the Khmer Rouge — even portraits of Pol Pot. These are big, hefty chapters, making the book an indispensable guide to this vast movement.”

- Leo Damrosch, The Club: Johnson, Boswell, and the Friends Who Shaped an Age (Yale University Press, 2019) “. . . brilliantly brings together the members’ voices. They air their opinions with the aplomb of thinkers who relish the English language, roll its tones and innuendos about their tongues and have the alertness to listen as well as speak.”

- George F. Will, The Conservative Sensibility (Hatchette Books, 2019): “Conservatism for Will is the defense of an a priori truth asserted as ‘self-evident’ by the founding fathers: that all men are created equal, and each has a “natural right” to do as he pleases with himself and his own property, and any government is tasked purely for the maintenance of such freedom.”

- Wolfram Eilenberger, Time of the Magicians: Wittgenstein, Benjamin, Cassirer, Heidegger, and the Decade that Reinvented Philosophy (Penguin Press, 2020), “begins in 1919 and ends in 1929, elegantly tracing the life and work of four figures who transformed philosophy in ways that were disparate and not infrequently at odds.”

- Katie Mack, The End of Everything (Astrophysically Speaking) (Scribner, 2020): “Most of what astronomers know comes not from seeing but from deduction — complex ladders of logic, building upon one another.”

- Alex Ross, Wagnerism: Art and Politics in the Shadow of Music (Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2020): “Richard Wagner: composer, conductor, dramatist, poet, polemicist, anarchist, Teutonic nationalist, anti-Semite, feminist, pacifist, vegetarian, animal rights activist — the man was the walking, talking definition of ‘protean genius.’ His life and his legacy was and remains to this day a continuum in which enchantment, even ravishment, comes hand in hand with provocation and controversy, adoration and loathing.”

- Zachary Carter, The Price of Peace: Money, Power, and the Life of John Maynard Keynes (Random House, 2020): “Ideas, no matter how abstract, always originate in lived experience. Carter situates the development of Keynes’s economic thought in relation to his social milieu.”

- Benjamin M. Friedman, Religion and the Rise of Capitalism (Knopf, 2021): “What does an esoteric concept like Calvinist soteriology have to do with the rise of modern economics? Does laissez-faire have its roots in the arcane Quinquarticular Controversy? Can one find the origins of the welfare state in postmillennialist eschatology?”

- Louis Menand, The Free World: Art and Thought in the Cold War (Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2021): the author’s “larger point, backed by a mountain of research and reams of thoughtful commentary, is that American culture ascended in this era for the right reasons: ‘Ideas mattered. Painting mattered. Movies mattered. Poetry mattered.'”

- Gal Beckerman, The Quiet Before: On the Unexpected Origins of Radical Ideas (Crown, 2022): “Radicals Used to Make Change. Then Social Media Happened.”

Ideas and the individual:

- Vivian Gornick, Fierce Attachments: A Memoir (Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1987): “The book is propelled by Gornick’s attempts to extricate herself from the stifling sorrow of her home — first through sex and marriage, but later, and more reliably, through the life of the mind, the ‘glamorous company’ of ideas.”

Technical and Analytical Readings

- Lawrence M. Krauss, A Universe from Nothing: Why There Is Something Rather Than Nothing (Free Press, 2012): the author takes on a Herculean task, probably one well beyond his reach, but at least he approaches the great question from a new angle.

Photographs

Documentary and Educational Films

Documentaries on philosophy and ideas:

- Various documentaries on the history of thought

- Histories of political thought

- Histories of Western thought

- Histories of

- Rothbard’s history of economic thought

- Richard Tarnas on Western thought: Part 1, Part 2, Part 3: “The Modern Worldview”, Part 4, Part 5.

- Quentin Skinner on the history of ideas

- Brief BBC videos on ideas in history

- “School of Life” history of ideas series

- “What is Intellectual History and Why Does It Matter?”

Imaginary

Fictional Narratives

I have endeavoured in this Ghostly little book, to raise the Ghost of an Idea, which shall not put my readers out of humour with themselves, with each other, with the season, or with me. May it haunt their houses pleasantly, and no one wish to lay it. [Charles Dickens, A Christmas Carol (1843), Preface.]

Ideas in fiction:

- David Mitchell, The Thousand Autumns of Jacob de Zoet: A Novel (Random House, 2010): “. . . a novel of ideas, of longing, of good and evil and those who fall somewhere in between.”

- Matthew Carr, The Devils of Cardena: A Novel (Riverhead Books, 2016): “Belamar’s residents continue to observe and celebrate their Islamic faith in private while pretending to be Catholics in public. The Old Christians are suspicious of the New Christians, each side demonizing the other, resulting in frequent outbreaks of violence . . .”

- Ian McEwan, Machines Like Me: A Novel (Nan A. Talese, 2019), “is a sharply intelligent novel of ideas. McEwan’s writing about the creation of a robot’s personality allows him to speculate on the nature of personality, and thus humanity, in general.”

Other novels:

- Andrew Lipstein, Last Resort: A Novel (Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2022): “. . . a Writer Turns a Friend’s Story Into a Smash Success”.

Poetry

- Edgar Lee Masters, “Franklin Jones”

Music: Composers, artists, and major works

Johann Sebastian Bach, Musikalisches Opfer (A Musical Offering), BWV 1079 (1747) (approx. 47-53’) (list of recorded performances): “Frederick then challenged Bach to improvise a fugue in six voices on the same subject. However, since the subject was clearly chosen to be a difficult one, and since Bach found that "the improvisation did not want to succeed as befitted such an excellent theme," he chose another subject on which he improvised a six-voice fugue to the amazement of the king and the court. On his return to Leipzig, Bach wrote a collection of music exploring the possibilities of Frederick's theme.”

On the power of ideas:

- Einar Englund, The Great Wall of China (1949) (approx. 20’): the work draws on oppression and tyranny in China. Max Frisch’s play, “The Chinese Wall” was the starting point. “The music, according to the composer, does not contribute to the satire of the theatrical play, but rather suggests, 'that no wall is strong enough to keep out ideas and influences.'” Eri Klas conducted the Tampere Philharmonic Orchestra in a performance, in 1999.

Music history, like the history of any dynamic human endeavor, is in substantial part a history of ideas. Arnold Schoenberg’s music well represents the musical idea, in his development of the twelve-tone compositional method. Any number of other composers, or artists could be used equally well. His works include:

- 5 Pieces for Orchestra, Op. 16 (1909) (approx. 17’) (list of recorded performances)

- Erwartung (Expectation), Op. 17 (1909) (approx. 28-31’) (list of recorded performances)

- Dreimal sieben Gedichte aus Albert Girauds 'Pierrot lunaire' (Three Times Seven Poems from Albert Giraud’s ‘Pierrot lunaire’), a/k/a Pierrot lunaire, Op. 21 (1912) (approx. 41-46’) (list of recorded performances)

- Serenade for Clarinet, Bass Clarinet, Mandolin, Guitar, Violin, Viola, Cello and a deep Male Voice, Op. 24 (1923) (approx. 32’) (list of recorded performances)

- Suite for 2 Clarinets, Bass Clarinet, Violin, Viola, Cello and Piano, Op. 29 (1926) (approx. 22-30’) (list of recorded performances)

- Variations for Orchestra, Op. 31 (1927) (approx. 22-23’) (list of recorded performances)

- Ode to Napoleon Bonaparte, Op. 41 (1942) (approx. 15-16’) (list of recorded performances)

Max Reger’s works for cello and piano, which, in addition to several short pieces, include:

- Cello Sonata No. 1 in F Minor, Op. 5 (1892) (approx. 26-35’) (list of recorded performances)

- Cello Sonata No. 2 in G Minor, Op. 28 (1898) (approx. 22’) (list of recorded performances)

- Cello Sonata No. 3 in F Major, Op. 78 (1904) (approx. 29’) (list of recorded performances)

- Cello Sonata No. 4 in A Minor, Op. 116 (1910) (approx. 30’) (list of recorded performances)

Works consisting of short pieces, little more than the germ of an idea:

- Charles Koechlin, 14 Pieces for Flute & Piano, Op. 157b (1936) (approx. 12’) (list of recorded performances)

- Charles-Valentin Alkan, 48 Motifs (Esquisses), Op. 63 (1861) (approx. 120’) (list of recorded performances)

- Georg Philipp Telemann, 100 Menuets, TWV 34:1-100 (1730) (approx. 134’)

- Alberto Ginastera, short piano pieces (approx. 108’)

- Gabriel Fauré, 8 Pièces Brèves, Op. 84 (1869-1902) (approx. 18-20’) (list of recorded performances)

- Mieczysław Weinberg, 12 Miniatures for flute and string orchestra, Op. 29bis (1945/1983) (approx. 12’) (list of recorded performances) (flute and piano)

- György Kurtág, Játékok (Games): “In 1973, György Kurtág began composing piano miniatures to which he gave the collective title of Játékok (Games). He has continued to add to the series, so that (as of 2025) there are well over 400 such pieces . . . The pieces, rarely more than a couple of minutes long and sometimes lasting just a few seconds, were first intended as didactic exercises, designed to elucidate a musical point or a detail of keyboard technique, but the collection soon began to encompass other occasional works and more personal expressions – birthday greetings, tributes and memorials to friends and fellow musicians, paraphrases of other music – becoming a complete encyclopedia of Kurtág’s compositional methods.”

Other works:

- Henri Dutilleux, Sur le meme accord (On Only One Chord) (2002) (approx. 8-9’) (list of recorded performances): in this nocturne for violin and orchestra, the musical idea consists of six notes, which are developed in many expressions.

- Einar Englund, Symphony No. 6, "Aphorisms" (1984) (approx. 33’)

- Henry Purcell, 8 Suites for harpsichord (1696) (approx. 46’) (list of recorded performances)

- Antonin Dvořák, Scherzo capriccioso, Op. 66, B. 131 (1883) (approx. 12-13’) (list of recorded performances)

- Robert Gibson, chamber music

- Katherine Hoover, Piano works (approx. 72’)

Albums:

- Idée Manu, “Oktopus: The Music of Boris Blacher” (2018) (44’) – though Blacher was not a jazz composer, apparently his musical ideas inspired this album.

- Simon Johnson, “B.A.C.H: Anatomy of a Motif” (2022) (135’): “Organist Simon Johnson presents this album as an exploration of the B-A-C-H motif in organ music, beginning with its appearance in 'The Art of Fugue, BWV 1080,' of Bach himself.”

- Bruce Wolosoff, “A Light in the Dark” (2013): “Bruce Wolosoff’s original score lends a once-upon-a-time melodic backdrop that evokes the gentility of late 19th-century society in the American South, yet supports the characters’ contrasting motifs with contemporary phrasing.”

- La Spagna, “Sopra La Spagna” (2021) (75’): an album of Renaissance and Baroque pieces, all based on the tune “La Spagna”

- Marc-André Hamelin, new piano works (2024) (74’) consists of new compositions for piano by one of the world’s greatest pianists.

- Pierre-Laurent Aimard, Schubert: Ländler (2024) (68’): brief waltzes, other dances and other baubles by a master composer, performed by a great pianist.

Histories of the development of musical forms:

- Daniel Saulnier, Gregorian Chant: A Guide to the History and Liturgy (Paraclete Press, 2009).

- Mark Everist, French Motets in the Thirteenth Century: Music, poetry and genre (Cambridge University Press, 1994).

- Suzanne Lord, Music in the Middle Ages: A Reference Guide (Greenwood, 2008).

- Roger Parker, ed., The Oxford Illustrated History of Opera (Oxford University Press, 1995).

- Donald Grout and Hermine Wiegel Williams, A Short History of Opera (Columbia University Press, 2003): its 1042 pages trace the development of the operatic form.

- Harold Owen, Modal and Tonal Counterpoint: From Josquin to Stravinsky (Schirmer, 1992).

- Douglass M. Green and Evan Jones, The Principles and Practice of Modal Counterpoint (Routledge, 2010).

- Douglass M. Green and Evan Jones, The Principles and Practice of Tonal Counterpoint (Routledge, 2015).

- Gioseffo Zarlino, The Art of Counterpoint (DaCapo, 1982).

- Jean Philippe Rameau, Treatise on Harmony (1722).

- Richard Hudson, The Allemande, the Balletto, and the Tanz: Volume 1: The History; Volume 2: The Tanz (Cambridge University Press, 1986).

- Alfred Dürr, The Cantatas of J.S. Bach (Oxford University Press, 2005).

- Eric Chafe, Analyzing Bach Cantatas (Oxford University Press, 2000).

- Michael Thomas Roeder, A History of the Concerto (Amadeus Press, 2003).

- Howard E. Smither, A History of the Oratorio, Volume 1: The Oratorio in the Baroque Era: Italy, Vienna, Paris (The University of North Carolina Press, 1977).

- Howard E. Smither, A History of the Oratorio, Volume 2 The Oratorio in the Baroque Era: Protestant Germany and England (The University of North Carolina Press, 1977).

- Howard E. Smither, A History of the Oratorio, Volume 3: The Oratorio in the Classical Era (The University of North Carolina Press, 1987).

- Howard E. Smither, A History of the Oratorio, Volume 4: The Oratorio in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries (The University of North Carolina Press, 2000).

- Charles M. Joseph, Stravinsky and Balanchine: A Journey of Invention (Yale University Press, 2002).

Music: songs and other short pieces

- Billy Joel, "We Didn't Start the Fire" (lyrics)

- Indigo Girls, “Galileo” (lyrics)

Visual Arts

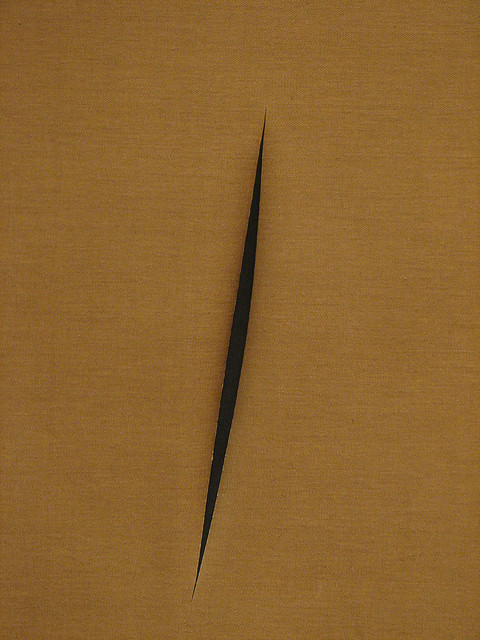

- Lucio Fontana, Concept Spatiale (1959)

- René Magritte, Clear Ideas (1958)

- Lucio Fontana, Concept Spatiale New York 10

- Salvador Dali, Surrealist Architecture (1932)

- René Magritte, The Cultivation of Ideas (1927)

- Mikalojus Ciulionas, The Thought (1904)