- A culture that does not grasp the vital interplay between morality and power, which mistakes management techniques for wisdom, which fails to understand that the measure of a civilization is its compassion, not its speed or ability to consume, condemns itself to death. [Chris Hedges, Empire of Illusion: The End of Literacy and the Triumph of Spectacle (Nation Books, 2009), p. 103).

- We have bought hook, line and sinker into the idea that education is about training and “success,” defined monetarily, rather than learning to think critically and to challenge. [Chris Hebdon, quoted in Chris Hedges, Empire of Illusion: The End of Literacy and the Triumph of Spectacle (Nation Books, 2009), p. 95.]

Critical thinking is the method and practice of subjecting propositions to reason and evidence. It demands the discipline of objectivity, the art of open-mindedness, and the curiosity and drive to discover the truth.

Critical thinkers make their greatest contributions in opposition to widespread pressure to believe unfounded propositions. The critical thinker often will be accused of contrariness merely because he declines to accept a proposition that others wish to believe. Like nature, sound thinking does not care what we wish, so the critical thinker must be prepared to withstand social pressure and simultaneously must guard against his own biases, including any personal inclination toward contrariness. This does not require a Spock-like blindness to the emotional side of life but it does require an awareness of the gap between emotion and reality and a determination to find the path that best leads to truth.

Real

True Narratives

Book narratives:

- Thomas E. Ricks, Churchill and Orwell: The Fight for Freedom (Penguin Press, 2017). “ . . . what comes across strongly in this highly enjoyable book is the fierce commitment of both Orwell and Churchill to critical thought. Neither followed the crowd. Each treated popularity and rejection with equal skepticism.”

- Pekka Hämäläinen, Lakota America: A New History of Indigenous Power (Yale University Press, 2019): “Pekka Hamalainen’s impressive history is also a quarrel with the field, with how history — especially the history of indigenous Americans — has been told and sold.”

- Harvey Sachs, Schoenberg: Why He Matters (Liveright, 2023): Schoenberg “exhibited a lifelong truculence toward any and all conventions that he himself had not examined firsthand.”

- Tim Alberta, The Kingdom, The Power, and the Glory: American Evangelicals in an Age of Extremism (Harper): “What he finds . . . is that under the veneer of Christian modesty simmers an explosive rage, propelling Americans who piously declare their fealty to Jesus to act as though their highest calling is to own the libs.”

- Robin Reames, The Ancient Art of Thinking for Yourself: The Power of Rhetoric in Polarized Times (Basic Books, 2024): “Reames, a specialist in rhetoric, sees us as unsuitably numb to the fact that our opinions are conditioned by what we already believe rather than springing from incontrovertible truth. She hopes that we can learn from the consciously honed rhetorical techniques of the ancient Greeks and Romans, among whom the art of argument was elevated in political discourse to an extent that seems almost unthinkable today.”

Technical and Analytical Readings

Video on critical thinking

Book narratives:

- Jonathan Lavery, William Hughes and Katheryn Doran, Critical Thinking: An Introduction to the Basic Skills (Broadview Press, 6th Edition, 2009).

- Brooks Noel Moore and Richard Parker, Critical Thinking (McGraw-Hill Humanities, 9th Edition, , 2008).

- Tracy Bowell and Gary Kemp, Critical Thinking: A Concise Guide (Routledge, 3rd Edition, 2009).

- M. Neil Browne and Stuart M. Keeley, Asking the Right Questions: A Guide to Critical Thinking (Prentice Hall, 9th Edition, 2009).

- Theodore Schick and Lewis Vaughn, How to Think About Weird Things: Critical Thinking for a New Age (McGraw-Hill Humanities, 9th Edition, 2010).

- Carl Sagan, The Demon-Haunted World: Science As a Candle In the Dark (Ballantine Books, 1997).

- Peter A Facione, "Critical Thinking: A Statement of Expert Consensus for Purposes of Education Assessment and Instruction. Research Findings and Recommendations," Education Resources Information Center, 1990.

- Alec Fisher, Critical Thinking: An Introduction (Cambridge University Press, 2nd edition, 2011).

- John Butterworth and Geoff Thwaites, Thinking Skills: Critical Thinking and Problem Solving (Cambridge University Press, 2nd edition, 2013).

- Robert Sternberg, Henry L. Roediger III and Diane F. Halpern, Critical Thinking in Psychology (Cambridge University Press, 2006).

- Robert Cogan, Critical Thinking Step By Step (University Press of America, 1998).

- Stephen H. Jenkins, Tools for Critical Thinking in Biology (Oxford University Press, 2015).

- Tim John Moore, Critical Thinking and Language: The Challenge of Generic Skills and Disciplinary Discourse (Bloomsbury Academic, 2011).

- A.O. Scott, Better Living Through Criticism: How to Think About Art, Pleasure, Beauty, and Truth (Penguin Press, 2016): “ . . . criticism, rather than being a lesser sibling of Art, is its equal — codependent and symbiotically related to the creative arts, each unthinkable without the other.”

- Duncan J. Watts, Everything Is Obvious, Once You Know the Answer (Crown Business, 2011): “We rely on common sense to understand the world, but in fact it is an endless source of just-so stories that can be tailored to any purpose. ‘We can skip from day to day and observation to observation, perpetually replacing the chaos of reality with the soothing fiction of our explanations,’ Watts writes.”

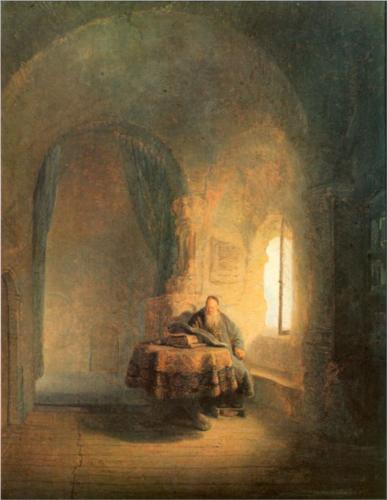

Photographs

Documentary and Educational Films

Imaginary

Fictional Narratives

I set down one time back in the woods, and had a long think about it. I says to myself, if a body can get anything they pray for, why don't Deacon Winn get back the money he lost on pork? Why can't the widow get back her silver snuffbox that was stole? Why can't Miss Watson fat up? No, says I to my self, there ain't nothing in it. [Mark Twain, The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (1906), Chapter III, “We Ambuscade the A-rabs”.]

"Why," said he, "a magician could call up a lot of genies, and they would hash you up like nothing before you could say Jack Robinson. They are as tall as a tree and as big around as a church." "Well," I says, "s'pose we got some genies to help _us_can't we lick the other crowd then?" "How you going to get them?" "I don't know. How do _they_ get them?" "Why, they rub an old tin lamp or an iron ring, and then the genies come tearing in, with the thunder and lightning a-ripping around and the smoke a-rolling, and everything they're told to do they up and do it. They don't think nothing of pulling a shot-tower up by the roots, and belting a Sunday-school superintendent over the head with itor any other man." "Who makes them tear around so?" "Why, whoever rubs the lamp or the ring. They belong to whoever rubs the lamp or the ring, and they've got to do whatever he says. If he tells them to build a palace forty miles long out of di'monds, and fill it full of chewing-gum, or whatever you want, and fetch an emperor's daughter from China for you to marry, they've got to do itand they've got to do it before sun-up next morning, too. And more: they've got to waltz that palace around over the country wherever you want it, you understand." "Well," says I, "I think they are a pack of flat-heads for not keeping the palace themselves 'stead of fooling them away like that. And what's moreif I was one of them I would see a man in Jericho before I would drop my business and come to him for the rubbing of an old tin lamp." “How you talk, Huck Finn. Why, you’d have to come when he rubbed it, whether you wanted to or not. "What! and I as high as a tree and as big as a church? All right, then; I _would_ come; but I lay I'd make that man climb the highest tree there was in the country." "Shucks, it ain't no use to talk to you, Huck Finn. You don't seem to know anything, somehow - perfect saphead." I thought all this over for two or three days, and then I reckoned I would see if there was anything in it. I got an old tin lamp and an iron ring, and went out in the woods and rubbed and rubbed till I sweat like an Injun, calculating to build a palace and sell it; but it warn't no use, none of the genies come. So then I judged that all that stuff was only just one of Tom Sawyer's lies. I reckoned he believed in the A-rabs and the elephants, but as for me I think different. It had all the marks of a Sunday-school. [Mark Twain, The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (1906), Chapter III, “We Ambuscade the A-rabs”.]

Poetry

Music: Composers, artists, and major works

In some way(s), every renowned composer was/is a critical thinker. Bach adhered to his religious tradition, insisting that music must serve that purpose; yet he revolutionized Western music. Beethoven is widely regarded as the first Humanist composer, who made music explicitly about life in ways that no one else had done before. Great iconoclasts such as Stravinsky and Schoenberg openly defied musical conventions, as did John Cage, who challenged the definition of music itself. The works of any and all of these masters could be presented under this heading, as can lesser-known composers who made a point of thinking for themselves, as part of the art of composing.

Darius Milhaud’s eighteen string quartets tackle twentieth-century challenges, in strictly musical terms, with consummate intelligence. They suggest the risks of living in intriguing but perilous times, and an increasingly complex world. Milhaud “was the calm‚ still centre round which much of the hectic life of Paris in the ’20s revolved‚ he was an inspiring teacher‚ he was a muchloved friend‚ he was the composer of at least one masterpiece‚ La création du monde‚ and of a number of lighthearted gems from Catalogue de fleurs to Scaramouche. But he was also the composer of the Fifth Quartet. This work is the one that starts in four keys at once‚ prompting displeasure from Poulenc and a statement from SaintSaëns that such polytonal exercises do not constitute music but ‘un charivari’.” He explained his rationale for composing more string quartets than Beethoven had: “. . . in my mind, it was a way of taking up the defence of chamber music during a period when it was being sacrificed to the esthetic of mass-produced music, the esthetic of the music hall and of the circus.” As a whole, they display “. . . Milhaud's melodic gifts and sheer ingenuity in his command of polytonality, which he made his own . . .”

- Milhaud, String Quartet No. 1, Op. 5 (1912) (approx. 15’)

- Milhaud, String Quartet No. 2, Op. 16 (1915) (approx. 26’)

- Milhaud, String Quartet No. 3, Op. 32 (1916) (approx. 22’)

- Milhaud, String Quartet No. 4, Op. 46 (1918) (approx. 12’)

- Milhaud, String Quartet No. 5, Op. 64 (1920) (approx. 19’)

- Milhaud, String Quartet No. 6, Op. 77 (1922) (approx. 10’)

- Milhaud, String Quartet No. 7, Op. 87 (1925) (approx. 12’)

- Milhaud, String Quartet No. 8, Op. 121 (1932) (approx. 15’)

- Milhaud, String Quartet No. 9, Op. 140 (1935) (approx. 20’)

- Milhaud, String Quartet No. 10, Op. 218, “Birthday Quartet” (1940) (approx. 15’)

- Milhaud, String Quartet No. 11, Op. 232 (1942) (approx. 15’)

- Milhaud, String Quartet No. 12, Op. 252 (1945) (approx. 14’)

- Milhaud, String Quartet No. 13, Op. 268 (1946) (approx. 11’)

- Milhaud, String Quartet No. 14, Op. 291, No. 1 (1949) (approx. 17’)

- Milhaud, String Quartet No. 15, Op. 291, No. 2 (1949) (approx. 18’)

- Milhaud, String Quartet No. 16, Op. 303 (1950) (approx. 18’)

- Milhaud, String Quartet No. 17, Op. 307 (1950) (approx. 21’)

- Milhaud, String Quartet No. 18, Op. 308 (1951) (approx. 25’)

Galina Ustvolskaya lived and composed in the Soviet Union under Stalin, and thereafter. “She was dubbed ‘the lady with the hammer’ for the radically percussive nature of her music.” She studied under Shostakovich, who once “wrote to her saying ‘It is not you who are under my influence, but I who am under yours.’ Ustvolskaya was attracted to Shostakovich as a person, but his ‘dry and soulless’ music never appealed to her, as she told the entire world in the 1990s. Ustvolskaya's frank statements, her denunciation of her teacher and exposure of his ugly side, caused a great scandal and remain one of the reasons why her music is still rarely performed in Russia.” “The Russian composer's brutally uncompromising work has an elementality that's both horrifying and thrilling”. Of her work, she said: “If the fate of my music is that it shall endure for some time, then for thinking musicians, without the limitations of stereotypes, it will be understood that this music is new both in its intellectual sense as well as in its contents.” Her works, and albums of her music include:

- Schoenberg Ensemble & Robert de Leeuw, “Ustvolskaya: Compositions I, II and III” album (1994) (49’)

- Antonii Baryshevskyi, “Galina Ustvolskaya: Piano Sonatas Nos. 1-6” album (2017) (76’)

- Natalia Andreeva, “Russian Piano Music Series, vol. 11” album (2015) (91’)

- Concerto for Piano, String Orchestra, and Timpani (1946) (approx. 18-19’)

- Grand Duet for Violincello and Piano (1959) (approx. 24-31’)

- Duet for Violin and Piano (1964) (approx. 29’)

- Sonata for Violin and Piano (1952) (approx. 21-23’)

- Trio for Clarinet, Violin and Piano (1949) (approx. 16’)

Henry Cowell cut his own path in music, from his rural early life to his pioneering use of tone clusters. “Cowell began his life as a composer in one of the most unique times in music history, that is, the divisive tumult of the early twentieth-century arts scene. Although each generation attempts, to some extent, to break down or change the musical paradigms employed by the previous generation, experimental twentieth-century composers were dismantling the very definitions of music and beginning to look to the basic concepts of noise and sound for inspiration, rather than remaining within the confines of traditional schema.” “As a composer, Cowell was deeply affected by (his) love of world music, and he is known not for a single approach but for his lack of one . . .” “Free of the often confining attitudes which govern formal musical education, Cowell had come to view any sound as musical substance with which he could work, and his early music owes more to the influence of birdsong, machine noises and folk music than it does to any knowledge of earlier masterworks.” Here are some of his works, and albums of his music:

- Henry Cowell, “Piano Music” album (1993) (60’)

- Various artists, “New Music: Piano Compositions by Henry Cowell” album (1999) (71’)

- Symphony No. 11, “Seven Rituals of Music” (1954) (approx. 22’)

- “Homage to Iran” (1959) (approx. 13’)

Music: songs and other short pieces

- Green Day, “American Idiot” (lyrics)

- David Bowie, “Big Brother” (lyrics)

- Michael Jackson, “They Don’t Care About Us” (lyrics)

- Rush, "The Trees" (lyrics)

- Tool, "Schism" (lyrics)

Visual Arts

Film and Stage

- F for Fake: the brilliant Orson Welles explores through semi-documentary the art of trickery in film, both fictional and supposedly real

- Ace in the Hole: a satire on the public’s desire for tawdry “news”