By making distinctions, we identify things in contrast to other things.

- . . . the distinction between the past, present and future is only a stubbornly persistent illusion. [Albert Einstein]

- I don’t make a particular distinction between “high art” and “low art.” Music is there for everybody. It’s a river we can all put our cups into and drink it and be sustained by it. [John Williams]

- The discovery of personal whiteness among the world’s peoples is a very modern thing – a nineteenth and twentieth century matter, indeed. The ancient world would have laughed at such a distinction. [W. E. B. Du Bois]

- By object is meant some element in the complex whole that is defined in abstraction from the whole of which it is a distinction. [John Dewey]

***

A six-month-old child is in the process of mastering certain distinctions. He picks up a cloth toy and strikes it against his head; then he does the same thing with a wooden block. The child has experienced the distinction between soft and hard.

Nothing clearly delineates hard from soft. Most people probably would say that wood is hard. Yet some woods are said to be soft, as opposed to others that are said to be hard. In science, the distinction may not even correspond to common understanding.

In this model, we are describing distinctions as they correspond to human experience. This makes considerable sense in a model that offers a Way of ethical and religious living. Homo sapiens is a species that employs distinctions as a means of orientation: good and bad, good and evil, wisdom and folly, courage and cowardice, love and hate, and love and indifference, etc.

We are nearly halfway through a model that proposes a framework for a set of such distinctions. My intention is to offer a complete and systematic framework for a religious life grounded in a commitment to the worth and dignity of all persons, and scientific naturalism. All constructive suggestions and criticisms are welcome.

Real

True Narratives

Technical and Analytical Readings

Photographs

Documentary and Educational Films

Imaginary

Fictional Narratives

Poetry

When I died, the circulating library

Which I built up for Spoon River,

And managed for the good of inquiring minds,

Was sold at auction on the public square,

As if to destroy the last vestige

Of my memory and influence.

For those of you who could not see the virtue

Of knowing Volney's "Ruins" as well as Butler's "Analogy"

And "Faust" as well as "Evangeline,"

Were really the power in the village,

And often you asked me,

"What is the use of knowing the evil in the world?"

I am out of your way now, Spoon River,

Choose your own good and call it good.

For I could never make you see

That no one knows what is good

Who knows not what is evil;

And no one knows what is true

Who knows not what is false.

[Edgar Lee Masters, “Seth Compton”]

I - Opusculum paedagogum. The pears are not viols, / Nudes or bottles. / They resemble nothing else.

II - They are yellow forms / Composed of curves / Bulging toward the base. / They are touched red.

III - They are not flat surfaces / Having curved outlines. / They are round / Tapering toward the top.

IV - In the way they are modeled / There are bits of blue. / A hard dry leaf hangs / From the stem.

V - The yellow glistens. / It glistens with various yellows, / Citrons, oranges and greens / Flowering over the skin.

VI - The shadows of the pears / Are blobs on the green cloth. / The pears are not seen / As the observer wills.

[Wallace Stevens, “Study of Two Pears”]

Music: Composers, artists, and major works

People can recognize when they are being respected, and when they are not; when they are loved; when someone is acting with courage. We can recognize familiar faces at a glance. These are distinctions we make every day. Similarly, many people can identify their favorite popular singer in a few notes (obvious distinctions), and classical aficionados can identify performers who sound alike to most people (subtle distinctions, to the average listener).

Billie Holiday puts an exclamation point on the idea of a distinction – the distinction of a distinction. Her voice was not merely unique; it was distinctive. Anyone who has heard her, and remembers it, can recognize her voice in an instant: “Oh, that’s Billie Holiday”. Here is the complete Billie Holiday on Columbia, 1933-1944 (674’).

Ignaz Friedman was a classical pianist known for his distinctive playing. Music critic Harold C. Schoenberg wrote of him: “His style was completely his own, and it was marked by a combination of incredible technique, musical freedom (some called it eccentricity), a tone that simply soared, and a naturally big approach, with dynamic extremes that tended to make a Chopin mazurka sound like an epic. He handled a melodic line inimitably — deftly outlining it against the bass, never allowing it to sag, always providing interest by a unique stress or accent. As he thought big, he played big.” “Friedman’s playing is not for the faint of heart, particularly as the conception of Romanticism these days is much more sanitized than things actually were during that era and those that immediately followed it. The Polish performer’s pianism is bold and impetuous, quixotic and evocative, individual in a way that can be startling to some listeners today . . .” For most people, perhaps, the distinction is not obvious but for classical music aficionados, it is. Here is a link to his playlists.

Béla Bartók composed numerous short pieces for piano (list of recorded performances), each piece expressing one musical idea. To most ears, Bartók’s music is far from simple, yet Bartók’s piano pieces are succinctly expressed, like many of the distinctions we make in everyday life.

- 10 Easy Piano Pieces, Sz 39, BB 51 (1908) (approx. 15-17’) (list of recorded performances)

- 14 Bagatelles for Piano, Sz 38, BB 50, Op. 6 (1908) (approx. 25’) (list of recorded performances)

- 4 Dirges for Piano, Sz 45, BB 58, Op. 9a (1910) (approx. 11’) (list of recorded performances)

- 7 Sketches (Vázlatok) for Piano, Op. 9b, Sz 44 (1910) (approx. 11-13’) (list of recorded performances)

- Romanian Folkdances for Piano, Sz 56, BB 68 (1915) (approx. 6’) (list of recorded performances)

- Suite for Piano, Op. 14, Sz 62, BB 70 (1916) (approx. 8-9’) (list of recorded performances)

- 15 Hungarian Peasant Songs for Piano, Sz 71, BB 79 (1918) (approx. ) (list of recorded performances)

- 8 Improvisations on Hungarian Peasant Songs, Sz 74, BB 83, Op. 20 (1920) (approx. 11-13’) (list of recorded performances)

- Dance Suite (Táncsvit, or, Tánc-suite) for Piano, Sz 77, BB 86b (1925) (approx. 17’) (list of recorded performances)

- 9 Little Pieces for Piano, Sz 82 (1926) (approx. 16-18’) (list of recorded performances)

- Out of Doors (Szabadban) for Piano, Sz 81, BB 89 (1926) (approx. 14’) (list of recorded performances)

- Mikrokosmos, Sz 107, BB 105 (1926-1939) (approx. 150’) (list of recorded performances)

Other compositions:

- Milko Kelemen, Archetypon II, “Für Anton”, for orchestra, (1996) (approx. 24’) “is a summary of all the archetypical elements of the ‘Akkord des Eindrucksvollen” (per the composer).

- Roger Reynolds, Kokoro (1992) (approx. 27’) includes twelve distinctions.

- Zoltan Kodály, Hungarian Folk Music (Magyar Népzene), 62 folksongs for voice & piano (1962) (approx. 77’) (list of recorded performances)

- Alexander Glazunov, Une Fete Slave (Slav Holiday), Op. 26 (1888) (approx. 13’)

- Véronique Vella, Fine Line (2009) (approx. 7’) is “a nicely drawn tone poem with hints of the exotic, derived from Arthur Golden’s Memoirs of a Geisha.”

Albums:

- Sérgio Assad, Clarice Assad & Third Coast Percussion, “Archetypes” (2020) (54’): “There is no set number of archetypes; the list of twelve featured in this project resonated with the artists because they represent distinctly different characters who feel very familiar from stories, myths, legends, and our shared and personal histories.”

- Roger Eno & Brian Eno, “Mixing Colours” (2020) (75’) “is a double sound-painting made up of natural phenomena (in tracks such as Snow, Desert Sand) and colours (Ultramarine, Burnt Umber) that plays out as an intimate conversation.” Each track is titled as a color.

- Matthew Shipp Horn Quartet, “Strata” (1997) (59’): “Each section has its own character, as if Shipp was trying to create a whole from the void, make it manifest itself a bit at a time. His constructive interval work creates a sonic architecture that offers multifaceted freedoms to his horn players, and a blank check to Parker to go where thou will.”

- Abel Selaocoe, “Where Is Home” (2022) (55’): “The genre-blending album harnesses an intimate emotional energy that is disrupted by regular fiery outbursts . . . In recent years, Selaocoe’s ability to float above rigid genre categories has resulted in a growing influence among a classical music community increasingly conscious of its deference to longstanding traditions.”

- We can identify musicians by their distinctive sounds. The music ensemble Toasaves is complex in this way because it “brings together artists with different backgrounds, including Early Music (trecento, Flemish polyphony, Sephardic music) and music from Greece, Turkey, and Afghanistan”. Adding to the appeal, the group exhibits “a fascination for archaic Flemish folk songs and their relationship to early music and Eastern music”. Their album “Zwerver” (2022) (57’) is engaging for that reason, and because of their skills and musicianship.

- Béla Fleck, Zakir Hussain, Edgar Meyer & Rakesh Chaurasia, “As We Speak” (2023) (45’) presents four distinct voices – banjo, tabla, string bass and bansuri – of master musicians. The album “brings together their unique takes on Indian and Western Classical music, Jazz and Bluegrass. Weaving a sonic tapestry of banjo, tabla, double bass, and bansuri, these artists convene to make some of the most soulful, fascinating and undefinable music found in today’s world.”

- Kuba Cichocki, “Flowing Circles” (2023) (55’): Cichocki “elaborated, ‘I have the privilege, based on my experience performing straight-ahead jazz, Latin jazz, European classical music, and avant-garde music, to enjoy free music while also exploring the age-old concepts of melody, harmony and rhythm. Certainly, then, I appreciate the idea of a tradition in music, but by no means as a rigid and limiting concept. Rather, I see tradition as something fluid and connected to life: a direct line into the most basic and timeless ways of music-making.’ So the listener of the pianist’s new album, Flowing Circles, experiences Cichocki and his band searching and exploring for dimensions beyond, or between, those commonly explored. This includes music which cannot be easily classified as traditionalism or experimentalism . . .”

Music: songs and other short pieces

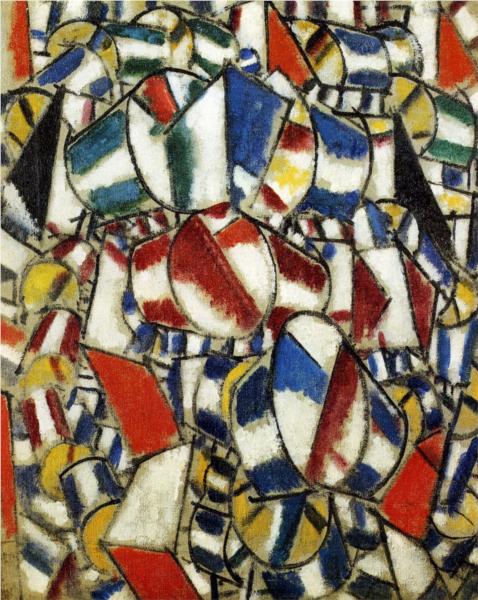

Visual Arts

- Georges Braque, The Blue Jug (1946)

- Wassily Kandinsky, Contrasting Sounds (1924)

- Joan Miró, North-South (1917)

- Kazemir Malevich, Suprematist Composition (purple rectangle over blue beam) (1916)

- Kazemir Malevich, Suprematist Painting (1917)

- Georges Braque, Violin and Glass (1913)

- Pierre Bonnard, The Red-Checkered Tablecloth (1910)