Evolution is a word for a process that applies to every dynamic system. It applies to biology, social systems (such as economics, politics and culture), and to our personal lives. To understand why and how things change, we must understand evolution.

- Evolution does not necessarily favor the longest-lived. It doesn’t necessarily favor the biggest or the strongest or the fastest, and not even the smartest. Evolution favors those creatures best adapted to their environment. That is the sole test of survival and success. [attributed to Harvey V. Fineberg]

- The first step in the evolution of ethics is a sense of solidarity with other human beings. [attributed to Albert Schweitzer]

- The point of human evolution is adapting to circumstance. Not letting go of the old, but adapting it, is necessary. [attributed to Sonali Bendre]

Evolution is the process that governs change in all dynamic systems, from biology to politics, economics and popular culture. Put another way, it is the driving force behind every dynamic system – every system that is not static. In nature and in life, one thing leads to another. That is the essence of evolution. Without evolution, life could never have become more complex than a single cell. Not only humans but also cats, dogs, gnats and sponges would never have existed.

Darwin’s grand insight on evolution of species may be the single greatest discovery in intellectual history. It is the glue and organizing principle that holds modern biology together. One cannot understand biology or any other dynamic system without understanding evolution.

As with Copernicus’ and Galileo’s conclusions about the solar system, evolution of species is not what many people wanted to hear. However, evolution of species is among the most strongly supported theories in science. Darwin’s observations made this clear. Then the fossil record was compiled, the theory being tested at every turn. As data accumulated, confirmation grew stronger. Biologists and other scientists in related fields started applying the theory successfully, further confirming the theory’s validity, based on its stunning track record in generating correct predictions. In recent decades, genetic science was developed, giving evolutionary theory’s detractors an opportunity to disprove the theory conclusively; instead, the theory correctly predicted what the genetic record would show.

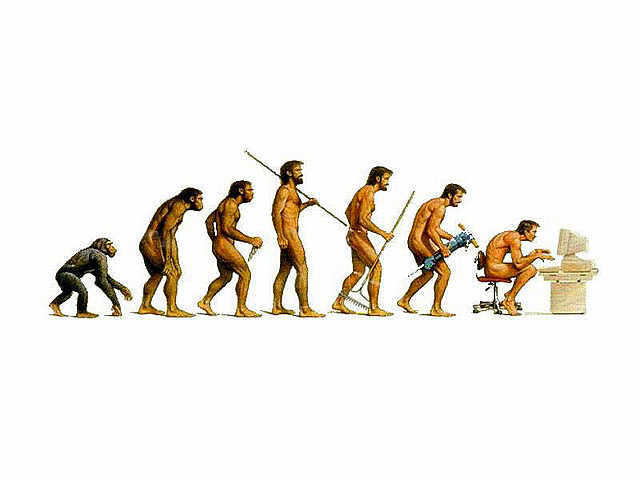

Evolution of species is a simpler process than most people realize. Monkeys do not turn into humans – that is not how it works. Instead, a genetic change is introduced into a population. The successful new genes are replicated, and spread within the population. Over time, many genetic changes may occur. A sexually reproducing species is defined by the ability of female and male species members to reproduce with each other. This ability depends on sufficiently similar genetic patterns in the mating pair. With enough genetic differences between the two, they can no longer reproduce. By definition, that is when a new species has emerged.

By understanding how evolution works, we can strip away the magical thinking that long dominated the subject matter. Why do nearly all mammals have nipples, including males? Evolutionary theory answers that question by applying reason to known facts. Understanding the step-by-step process is necessary to a comprehensive understanding of species.

Many people do not realize that evolution is not limited to biology. All dynamic systems evolve. Dick Fosbury was a high-jumper who went over the bar face-up instead of face-down, as had always been done. When other high jumpers saw that his strategy succeeded, nearly every high jumper adopted the successful strategy. Advertisers may be reluctant to use a controversial strategy – until someone does it successfully. In politics, successful candidates are defined as the ones who win elections. When a strategy succeeds, others will use it. If it succeeds generally, it will come to dominate the political population. Unsuccessful strategies will become extinct. These phenomena are manifestations of social evolution.

Biological and social evolution are not exactly the same. Humans can exert conscious control over social evolution, in ways that we cannot do in biological evolution – at least not historically. Human institutions such as cultures “radically (alter) the relationship between natural selection and cognition.”

Just as the mechanics of biological evolution bring understanding to that field, so do the dynamics of social evolution bring understanding to that field. For example, many people argue for term limits for elected officials. However, if the behavior of elected officials is being driven by campaign funding, and by who is likely to help them in post-political careers, then term limits are not likely to make any substantial difference in their behavior; sure enough, where term limits have been tried, they do not appear to have achieved their intended purpose of making governments less corrupt. That is because the system’s key dynamics have remained the same. To induce elected officials to behave less corruptly, we would have to enact enforceable laws that strike at the dynamics of why politicians behave corruptly now. All the slogans and promises will not make the slightest difference until that occurs. This is another illustration of why magical thinking must be replaced by scientific thinking – in this case, thinking that adequately accounts for the relevant behaviors, and the evolutionary processes surrounding them.

Here too, this is not what the people who dominate politics in the United States want to hear. The system works very well for them. Far better it is for them to keep the carrot dangling in front of the public, so that “the people” can have something to chase. We have many of our political troubles because far too few people understand the evolutionary process. Our departure from conventional thinking on this point is this: systems of human interaction, including social and political systems, and systems of laws, will never achieve desired ends for the people at large, until the people thoroughly understand the evolutionary principle and its central importance in and to every dynamic system.

The principle is simple. Behaviors that succeed are replicated, and become prevalent within the population. Behaviors that do not succeed die out. To design sound and effective systems of laws, this principle must be clearly understood, and kept firmly in mind; however, that alone is not enough. The centrality of evolution in driving dynamic systems must also be clearly understood, so that policy makers and the public are not distracted by bright shiny objects that bear no relation to the relevant behaviors; and people must be constantly on guard for pandering, because that has proved to be a successful political strategy far too often. Most likely, it will remain so until the people at large gain a clear understanding of what evolution is, and how it works.

Real

True Narratives

Histories of biological evolutionary theory:

- Ernst Mayr, One Long Argument: Charles Darwin and the Genesis of Modern Evolutionary Thought (Harvard University Press, 1991).

- Michael Ruse, The Darwinian Revolution: Science Red in Tooth and Claw (University of Chicago Press, 1979).

- Peter J. Bowler, Evolution: The History of an Idea (University of California Press, 1992).

- Charles Darwin, The Voyage of the Beagle (1839).

- Carl Zimmer, Evolution: The Triumph of an Idea (Harper Collins, 2001).

- Marlene Zuk, Sex on Six Legs: Lessons on Life, Love, and Language from the Insect World (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2011): explaining “not only hos insects do what they do, but why”.

Histories of social evolution:

- Robert N. Bellah, Religion in Human Evolution: From the Paleolithic Age to the Axial Age (Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2011).

- Jay Bahadur, The Pirates of Somalia: Inside Their Hidden World (Pantheon Books, 2011): “ . . . buccaneering has evolved into a very modern activity, complete with night vision goggles, GPS units and even investment advisers”.

- David Sloan Wilson, The Neighborhood Project: Using Evolution to Improve My City, One Block at a Time (Little, Brown & Company, 2011): the evolutionary biologist describes how he applied evolutionary principles to changing Binghamton, New York, one block at a time.

- Harry Petroski, The Evolution of Useful Things: How Everyday Artifacts – From Forks and Pins to Paper Clips and Zippers – Came to Be as They Are (Vintage, 1994).

- Sylvia Nasar, Grand Pursuit: The Story of Economic Genius (Simon & Schuster, 2011): on the evolution of modern economic thought.

- Tim Alberta, American Carnage: On the Front Lines of the Republican Civil War and the Rise of President Trump (Harper, 2019): “. . . it’s a fascinating look at a Republican Party that initially scoffed at the incursion of a philandering reality-TV star with zero political experience and now readily accommodates him.”

- Tony Ashworth, Trench Warfare 1914-1918: The Live and Let Live System (MacMillan, 1980) (chronicling evolution of cooperation in the trenches).

- Gerd Carling, ed., The Mouton Atlas of Languages and Cultures (De Gruyter Mouton, 2019).

- Oliver Roeder, Seven Games: A Human History (W.W. Norton & Company, 2022): “Are games more than their rules and playing pieces? Are they metaphors for deeper truths of the human experience? Is chess ‘life in miniature,’ as the former world champion Garry Kasparov once said? Or is it just a board game — Risk with more rules and a boring map?”

- Sylvia Ferrara, The Greatest Invention: A History of the World in Nine Mysterious Scripts (Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2022): “. . . Ferrara develops a bold argument. The standard history of writing has long held that the first real script was invented by Mesopotamian clerks. . . . One day, one of the clerks might have noticed that the image representing, say, cane — gi — could do double duty by also representing the verb ‘to reimburse,’ which in Sumerian sounds the same. Such realizations gave birth to hundreds of signs that represented enough syllables to capture an entire language.”

- Laurie Winer, Oscar Hammerstein II and the Invention of the Musical (Yale University Press, 2023): “Sondheim looms large in Winer’s book, and in their paired, opposed careers the two men go a long way toward illuminating the evolution of the American musical in the 20th century.”

- Robyn Schiff, Information Desk: An Epic (Penguin Books, 2023), “is about many things, at its core is the idea that one work of art begets another.”

- Peter Ames Carlin, The Name of This Band is R.E.M.: A Biography (Doubleday, 2024), “. . . chronicles the rise of an indispensable band and the evolution of its music.”

Technical and Analytical Readings

- John A. Long, The Rise of Fishes: 500 Million Years of Evolution (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2005).

- George W. Barlow, The Cichlid Fishes: Nature's Grand Experiment In Evolution (Basic Books, 2000).

- Gene S. Helfman, Bruce B. Collette, Douglas E. Facey and Brian W. Bowen, The Diversity of Fishes: Biology, Evolution, and Ecology (Wiley-Blackwell, 2009).

- K.J. Willis and J.C. McElwain, The Evolution of Plants (Oxford University Press, 2nd edition, 2014).

- Wilson N. Stewart and Gar W. Rothwell, Paleobotany and the Evolution of Plants (Cambridge University Press, 2010).

- David Grimaldi and Michael S. Engel, Evolution of the Insects (Cambridge University Press, 2005).

- Donald R. Prothero, Evolution: What the Fossils Say and Why It Matters (Columbia University Press, 2007).

- Brian Switek, Written In Stone: Evolution, the Fossil Record, and Our Place In Nature (Bellevue Literary Press, 2010).

- Robert Carroll, The Rise of Amphibians: 365 Millions Years of Evolution (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2009).

- Donald R. Prothero and Scott F. Ross, The Evolution of Arodactyls (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2007).

- Kenneth D. Rose, The Beginning of the Age of Mammals (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2006).

- Donald R. Prothero, After the Dinosaurs: The Age of Mammals (Indiana University Press, 2006).

- Donald R. Prothero, Horns, Tusks, and Flippers: The Evolution of Hoofed Mammals (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2003).

- Jordi Agusti and Mauricio Anton, Mammals, Sabertooths, and Hominids: 65 Million Years of Mammalian Evolution (Columbia University Press, 2002).

- Alan Turner and Mauricio Anton, Evolving Eden: An Illustrated Guide to the Evolution of African Large-Mammal Fauna (Columbia University Press, 2004).

- Kenneth D. Rose, The Rise of Placental Mammals: Origins and Relationships of the Major Extant Clades (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2005).

- Ivan R. Schwab, Evolution's Witness: How Eyes Evolved (Oxford University Press, 2011).

- Andrew Parker, In the Blink of an Eye: How Vision Sparked the Big Bang of Evolution (Basic Books, 2003).

- T.S. Kemp, The Origin & Evolution of Mammals (Oxford University Press, 2005).

- Peter S. Ungar, Mammal Teeth: Origin, Evolution, and Diversity (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2010).

- J.G.M. Thewissen and Sirpa Nummela, eds., Sensory Evolution on the Threshold: Adaptations in Secondarily Aquatic Vertebrates (University of California Press, 2008).

- Alan Walker and Pat Shipman, The Ape in the Tree: An Intellectual and Natural History of Proconsul (Belknap Press, 2005).

- Charles Darwin, On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or, The Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life (John Murray, 1859).

- Ernst Mayr, What Evolution Is (Basic Books, 2001).

- Nick Lane, Life Ascending: The Ten Great Inventions of Evolution (W.W. Norton & Co., 2009).

- Ernst Mayr, Evolution and the Diversity of Life: Selected Essays (Belknap Press, 1976).

- Richard Dawkins, The Greatest Show on Earth: The Evidence for Evolution (Free Press, 2009).

- Richard Dawkins, The Selfish Gene (Oxford University Press, 3rd Edition, 2006).

- Richard Dawkins, The Ancestor's Tale: A Pilgrimage to the Dawn of Evolution (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2004).

- Richard Dawkins, The Extended Phenotype: The Long Reach of the Gene (Oxford University Press, 1999).

- Stephen Jay Gould, The Structure of Evolutionary Theory (Belknap Press, 2002).

- Stephen Jay Gould, The Richness of Life: The Essential Stephen Jay Gould (W.W. Norton & Co., 2007).

- Niles Eldredge, Reinventing Darwin: The Great Debate at the High Table of Evolutionary Theory (Wiley, 1995).

- Jerry A. Coyne, Why Evolution Is True (Viking Adult, 2009).

- J. Maynard Smith, The Theory of Evolution (Cambridge University Press, 1993).

- E.N.K. Clarkson, Invertebrate Peleontology and Evolution (Springer, 4th Edition, 1992).

- Ernst Mayr, Systematics and the Origin of Species from the Viewpoint of a Zoologist (Columbia University Press, 1942).

- Julian Huxley, Evolution: The Modern Synthesis (Harper and Brothers, 1942).

- Theodosius Dobzhansky, Genetics and the Origin of Species (Columbia University Press, 1937).

- J.B.S. Haldane, The Causes of Evolution (Longmans, Green & Co., 1932).

- John F. Hoffecker, Landscape of the Mind: Human Evolution and the Archaeology of Thought (Columbia University Press, 2011).

- Merlin Sheldrake, Entangled Life: How Fungi Make Our Worlds, Change Our Minds, and Shape Our Futures (Random House, 2020): “This book may not be a psychedelic — and unlike Sheldrake, I haven’t dared to consume my copy (yet) — but reading it left me not just moved but altered, eager to disseminate its message of what fungi can do.”

Interactive works, cladograms, and scholarly articles:

- Tree-of-life explorer;

- Lifemap;

- Taxonomy database;

- Simple tree-of-life clagogram;

- Vertebrate cladogram;

- List of scholarly articles on phylogenetic relationships.

JOURNALS on BIOLOGICAL EVOLUTION

- International Journal of Organic Evolution

- Journal of Evolutionary Biology

- International Journal of Evolutionary Biology

- Journal of Human Evolution

- BMC Evolutionary Biology

- Genome Biology and Evolution

- Journal of Evolutionary Biology Research

- Evolution and Human Behavior

- Cladistics

SOCIAL EVOLUTION

- Andrew F.G. Bourke, Principles of Social Evolution (Oxford University Press, 2011).

- Robert Trivers, Social Evolution (Benjamin Cummings, 1985).

- Robert Trivers, Natural Selection and Social Theory: Selected Papers of Robert Trivers (Oxford University Press, 2002).

- Jonathan Birch, The Philosophy of Social Evolution (Oxford University Press, 2017).

- Andrew F.G. Bourke, Social Evolution in Ants (Princeton University Press, 1995).

- Keith S. Delaplane, Honey Bee Social Evolution: Group Formation, Behavior, and Preeminence (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2024).

- Alex Mesoudi, Cultural Evolution: How Darwinian Theory Can Explain Human Culture and Synthesize the Social Sciences (University of Chicago Press, 2011).

- Ronald F. Inglehart, Cultural Evolution: People's Motivations are Changing, and Reshaping the World (Cambridge University Press, 2018).

- Brian Skyrms, The Stag Hunt and the Evolution of Social Structure (Cambridge University Press, 2004).

- Steven J. Pope, The Evolution of Altruism & the Ordering Of Love (Georgetown University Press, 1995).

- Dorothy L. Cheney & Robert M. Seyfarth, Baboon Metaphysics: The Evolution of a Social Mind (University of Chicago Press, 2008).

- Brian Skyrms, Evolution of the Social Contract (Cambridge University Press, 1996).

- Robert Axelrod, The Evolution of Cooperation (Basic Books, 2006).

- John Andreas Olsen and Martin van Creveld, eds., The Evolution of Operational Art: From Napoleon to the Present (Oxford University Press, 2010).

- Alfred C Haddon, Evolution in Art (1895).

- Ben West, The American Musical: Evolution of an Art Form (Routledge, 2024).

- Steven Jan, Music in Evolution and Evolution in Music (Open Book Publishers, 2022).

- Miriam Piilonen, Theorizing Music Evolution: Darwin, Spencer, and the Limits of the Human (Oxford University Press, 2024).

- John Simpson, The Word Detective: Searching for the Meaning of It All at the Oxford English Dictionary (Basic Books, 2016): “John Simpson joined the dictionary in the mid-1970s, in the era of the Supplement, which was overseen by the New Zealander Robert Burchfield. Simpson worked his way up, and by the time he retired in 2013 he was chief editor.”

- John McWhorter, Words On the Move: Why English Won’t – and Can’t – Sit Still (Like, Literally) (Henry Holt & Company, 2016): “McWhorter first staggers you with a glittering analogy, and then, once you are off-guard, he bombards you with so many (brilliant) examples that resistance is both useless and out of the question.”

- Richard W. Bailey, Speaking American: A History of English in the United States (Oxford University Press, 2012): “. . . Bailey argues that geography is largely behind our fluid evaluations of what constitutes ‘proper’ English.”

Game theory arises out of an understanding of evolutionary principles. Below are listed a few of the works in this field, with a representative example from each of several fields in which game theory is applied.

- Economics: John von Neumann and Oskar Morgenstern, Theory of Games and Economic Behavior (1953).

- Law: Douglas G. Baird, Robert H. Gertner and Randal C. Picker, Game Theory and the Law (Harvard University Press, 1994).

- Law and economics: John Cirace, Law, Economics, and Game Theory (Lexington Books, 2018).

- Ethics: Ken Binmore, Game Theory and the Social Contract, Volume 1: Playing Fair (MIT Press, 1994); Volume 2: Just Playing (MIT Press, 1998).

- Politics: Steven J. Brams, Game Theory and Politics (Dover Publications, 2013).

- Psychology: Andrew M. Colman, Game Theory and Its Applications (Psychology Press, 2017).

- Arms negotiations: Steve Weber, Cooperation and Discord in U.S.-Soviet Arms Control (Princeton University Press, 1991).

- Conflict resolution generally: Anatol Rapoport, Game Theory as a Theory of Conflict Resolution (Springer, 1974).

- Advertising and marketing: Thomas J. Webster, Analyzing Strategic Behavior in Business and Economics: A Game Theory Primer (Lexington Books, 2014).

- Card games: Michael Acevedo, Modern Poker Theory: Building an Unbeatable Strategy Based on GTO Principles (D&B Press, 2019).

Photographs

Documentary and Educational Films

Evolution, generally:

- Evolution: What Darwin Never Knew

- PBS documentary: Darwin’s Dangerous Idea; Great Transformations; Extinction; Evolutionary Arms Race; part 5; The Mind’s Big Bang; What About God?

- Biological Evolution: What It Is, and What It Isn’t

- How Evolution Works

- Introduction to Evolution and Natural Selection

- Ken Miller explains evolution

Abiogenesis:

- How Life Started on Earth

- How did life begin?

- The origin of life

- origin of life

- Prokaryotes (single-celled organisms)

Evolution of eukaryotes (multiple-celled organisms):

- Where Did Eukaryotic Cells Come From?

- The Evolution of Multicellular Life

- The Evolution of Aerobic Organisms and Eukaryotic Cells

- Origins of Eukaryotes

- The first major transition in evolution

Evolution of fungi:

- Fungal Evolution

- Fungus: The 3rd Kingdom

- How Mushrooms Changed the World

- Sequence all the fungi!

- Mushrooms, Evolution, and the Millennium

Evolution of plants:

- Plant Life

- Plant Evolution

- How Did Plants Evolve?

- Evolution of Flowering Plants (Angiosperms)

- The Revolution in Plant Evolution

Evolution of insects:

Evolution of invertebrates:

- Animals Without Backbones: The Invertebrate Story

- (12-part series)

- (27 videos)

- The Neglected Majority: Using Invertebrates to Study Evolution, Phylogeny and Biogeography

Evolution of vertebrates:

Evolution of animals:

Evolution of fish

Evolution of arthropods:

Evolution of tetrapods:

Evolution of reptiles:

Evolution of birds:

Evolution of mammals:

- The Evolution of Whales

- The Walking and Swimming Whale

- And the Mammals Laid Eggs

- From Reptile to Mammal

Evolution of primates:

- Ape to Man

- The Great Apes: The Baseline for Human Evolution

- Origins of Genus Homo

- Southern Africa and Origin of Homo

- The First Human

- The Last Neanderthals

- Homo Erectus Versus Homo Sapiens

- The Evolution of Humans

- Primate Evolution with Neil DeGrasse Tyson

Imaginary

Fictional Narratives

From a purely literary point of view, few studies would prove more curious and fruitful than the study of slang. It is a whole language within a language, a sort of sickly excrescence, an unhealthy graft which has produced a vegetation, a parasite which has its roots in the old Gallic trunk, and whose sinister foliage crawls all over one side of the language. This is what may be called the first, the vulgar aspect of slang. But, for those who study the tongue as it should be studied, that is to say, as geologists study the earth, slang appears like a veritable alluvial deposit. According as one digs a longer or shorter distance into it, one finds in slang, below the old popular French, Provençal, Spanish, Italian, Levantine, that language of the Mediterranean ports, English and German, the Romance language in its three varieties, French, Italian, and Romance Romance, Latin, and finally Basque and Celtic. A profound and unique formation. A subterranean edifice erected in common by all the miserable. Each accursed race has deposited its layer, each suffering has dropped its stone there, each heart has contributed its pebble. A throng of evil, base, or irritated souls, who have traversed life and have vanished into eternity, linger there almost entirely visible still beneath the form of some monstrous word. Do you want Spanish? The old Gothic slang abounded in it. Here is _boffete_, a box on the ear, which is derived from _bofeton; vantane_, window (later on _vanterne_), which comes from _vantana; gat_, cat, which comes from _gato; acite_, oil, which comes from _aceyte_. Do you want Italian? Here is _spade_, sword, which comes from _spada; carvel_, boat, which comes from _caravella_. Do you want English? Here is _bichot_, which comes from _bishop; raille_, spy, which comes from _rascal, rascalion; pilche_, a case, which comes from _pilcher_, a sheath. Do you want German? Here is the _caleur_, the waiter, _kellner_; the _hers_, the master, _herzog_ (duke). Do you want Latin? Here is _frangir_, to break, _frangere; affurer_, to steal, _fur; cadene_, chain, _catena_. There is one word which crops up in every language of the continent, with a sort of mysterious power and authority. It is the word _magnus_; the Scotchman makes of it his _mac_, which designates the chief of the clan; Mac-Farlane, Mac-Callumore, the great Farlane, the great Callumore41; slang turns it into _meck_ and later _le meg_, that is to say, God. Would you like Basque? Here is _gahisto_, the devil, which comes from _gaïztoa_, evil; _sorgabon_, good night, which comes from _gabon_, good evening. Do you want Celtic? Here is _blavin_, a handkerchief, which comes from _blavet_, gushing water; _ménesse_, a woman (in a bad sense), which comes from _meinec_, full of stones; _barant_, brook, from _baranton_, fountain; _goffeur_, locksmith, from _goff_, blacksmith; _guedouze_, death, which comes from _guenn-du_, black-white. Finally, would you like history? Slang calls crowns _les maltèses_, a souvenir of the coin in circulation on the galleys of Malta. [Victor Hugo, Les Miserables (1862), Volume IV – Saint-Denis; Book Seventh – Slang, Chapter II, “Roots”.]

Novels:

- Chaim Grade, Sons and Daughters: A Novel (1963), is “a sprawling and incident-packed novel, set during the 1930s in Poland and Lithuania, that is largely about rabbis and their wayward, modernity-seeking children.”

Poetry

Be glad your nose is on your face, / not pasted on some other place, / for if it were where it is not, / you might dislike your nose a lot.

Imagine if your precious nose / were sandwiched in between your toes, / that clearly would not be a treat, / for you’d be forced to smell your feet.

Your nose would be a source of dread / were it attached atop your head, / it soon would drive you to despair, / forever tickled by your hair.

Within your ear, your nose would be / an absolute catastrophe, / for when you were obliged to sneeze, / your brain would rattle from the breeze.

Your nose, instead, through thick and thin, / remains between your eyes and chin, / not pasted on some other place— / be glad your nose is on your face!

[Jack Prelutsky, “Be Glad Your Nose Is On Your Face” (1984)]

Music: Composers, artists, and major works

Music is a product of evolution in practically every way. Birdsongs, mating calls, warning calls and other forms of music in non-humans serve evolutionary functions. Human music is a product of our genetic development, which allows us to create more sophisticated music, in greater variety, than in any other species.

Music also undergoes social evolution. The Billboard top-100 list is a product of willing and able creators (the equivalent of a genetic pool) and eager recipients (the environment in which the music thrives, reproduces and multiplies). Every kind of music, in every part of the world, at every point in history, reflects the social evolution that led to its creation and its resilience as an art form. When people lose their taste for a kind of music, it quickly disappears from the environment – becomes extinct. Like all dynamic systems, music evolves.

The processes of musical evolution are remarkably similar to those of biological evolution; the core difference is that the musical idea replaces the gene, and as a result musical evolution can be directed. A musical form develops, then a new idea is introduced. As that idea is developed, the musical form changes in character. Eventually, a new form may begin to take shape. We will explore just a few examples of evolution in music.

The blues, with its distinctive form, began in the American South and could be seen as comfort music for troubled souls in troubled circumstances. As African-Americans migrated into the cities, so did the blues, taking root, most notably, in Chicago, Kansas City, St. Louis, Detroit, Memphis, Mississippi/Delta, and New York; each of these branches took on its own character, each spawning its own offspring, in Chicago, Kansas City, St. Louis, Detroit, Memphis, Mississippi/Delta, and New York.

Some blues singers, such as Olive Brown, “Empress of the Blues”, transcended any one blues tradition, probably because her roots were in several of them. An excellent compilation tracing the developmental history of the Blues is available. Excellent written histories of blues music are also available.

Jazz could be said to begin in New Orleans with Dixieland music but it also has much of its root system in the blues. Its developments have included hot, swing, cool, be-bop, funk, straight-ahead, free, avant-garde, modal and fusion.

Though the string quartet has an evolutionary history before Haydn, he developed the form as we now recognize it. Follow its evolutionary progression from a prototype through representative works from various composers. If you listen, you can hear it.

- Allesandro Scarlatti (composed early 1700s)

- Franz Xaver Richter (composed early-mid 1700s)

- Vincenzo Manfredini (composed mid-1700s)

- Franz Joseph Haydn (1763-75)

- Franz Joseph Haydn (1799)

- Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1790)

- Georges Onslow (composed 1806-1833)

- Juan Crisóstomo Arriaga (ca. 1820)

- Gaetano Donizetti, known mainly for his operas, composed eighteen string quartets early in the 19th

- Louis Spohr (composed 1807-1857)

- Franz Schubert (composed 1812)

- Ludwig van Beethoven (1825)

- Norbert Burgmüller (composed 1825-1835)

- Felix Mendelssohn (composed 1829-1847)

- Robert Schumann (composed 1842)

- Max Bruch (1859-1860)

- Johannes Brahms (three quartets, 1870s)

- Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky (composed 1871-1876)

- Charles Gounod (1895)

- Bedřich Smetana (1876-1883)

- Edvard Grieg (1878)

- Alexander Borodin (1881)

- Sergey Taneyev (1880-1905)

- Arthur Foote (1893)

- Alexander Glazunov (composed 1882-1930)

- Jean Sibelius (1909)

- Carl Nielsen (composed 1888-1919)

- César Franck: String Quartet in D Major, M9 (1889–90)

- Claude Debussy: String Quartet in G Minor, Op. 10, L85 (1893)

- Antonin Dvořák (1895)

- Alexandre von Zemlinsky (composed 1893-1936)

- Ralph Vaughan Williams (1898, 1944)

- Camille Saint-Saëns (composed 1899, 1918)

- Maurice Ravel, String Quartet in F Major (1903)

- Kurt Atterberg (1906-1908)

- York Bowen (1918-1919)

- Arnold Bax (composed 1918-1936)

- Josef Bohuslav Foerster, 5 string quartets (1888-1959)

- Darius Milhaud (composed 1912-1950)

- Jurgis Karnavičius (composed 1913-1925)

- Paul Hindemith (composed 1915-1945)

- Heitor Villa-Lobos (composed 1915-1957)

- Bohuslav Martinů (composed 1918-1947)

- Darius Milhaud (1912-1949)

- Alois Hába (composed 1919-1967)

- Alexandre Tansman (composed 1922-1956)

- Arthur Bliss (three quartets, composed 1914-1950)

- George Anthiel (composed 1925-1948)

- Hilding Rosenberg (composed 1920-1957)

- Franco Alfano (composed 1924-1949)

- Pavel Haas: String Quartet No. 2, "From the Monkey Mountains" (Z opičích hor), Op. 7 (1925)

- Henry Cowell (1936)

- Sergei Prokofiev (composed 1930, 1941)

- Walter Piston (composed 1933-1947)

- Ernest Bloch (1940s-1950s)

- Elizabeth Maconchy (composed 1933-1984)

- Béla Bartók (composed 1896-1939)

- William Alwyn (1953, 1975)

- Samuel Barber: String Quartet in B Minor, Op. 11, H88 (1936)

- Miecczysław Wienberg (a/k/a Vainberg) (composed 1937-1987)

- Dmitri Shostakovich (composed 1938-1974)

- Benjamin Britten (1941, 1945, 1975)

- Giacinto Scelsi (composed 1944-1974)

- Vagn Holmboe (composed 1945-1989)

- Alberto Ginastera (composed 1948-197 3)

- Leon Kirchner (composed 1949-1967)

- Robert Simpson (composed 1951-1987)

- Einojuhani Rautavaara (composed 1952, 1958)

- George Rochberg (composed 1952-1978)

- Peter Maxwell Davies (composed latter 20th century)

- Hayden Wayne (composed latter 20th century)

- György Ligeti (composed 1954, 1968)

- Luciano Berio (composed 1956-1993)

- Alfred Schnittke (composed 1966-1983)

- Gloria Coates (composed 1966-1999)

- David Matthews (composed 1970-1990s)

- George Crumb, Black Angels (1971)

- Henri Dutilleux: String Quartet, "Ainsi la nuit" (Thus the Night) (1976)

- Morton Feldman (1979)

- Daniel Asia: String Quartet No. 2 (1985)

- Henryk Górecki (composed 1988 and 1990)

- John Corigliano (1995)

- Carl Czerny (2000)

- Georg Friedrich Haas (2016)

- Catherine Lamb (2009, 2019)

The symphony has an equally rich evolutionary history and development, owing to the large number of voices available to the composer: for example, a string quartet cannot employ a mallet and a wooden box to strike a tragic blow, else it would no longer be a string quartet. This richness allows the composer, as Mahler put it, to “embrace everything” much as the human mind draws on its rich evolutionary history to think symbolically, imagine everything and begin to understand nature. Two composers stand out for their advancement of the symphonic form: Beethoven vastly expanded and enriched it, and Mahler deepened it and extended its reach.

- Franz Joseph Haydn (1761)

- Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1764, composed at age eight)

- Karl Ditters von Dittersdorf (1778)

- Carl Friedrich Abel (1785)

- Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1770)

- Ludwig van Beethoven's Symphony No. 1 is mainly an extension of Mozart’s work (1801)

- Felix Mendelssohn (1824)

- Beethoven (1824)

- Franz Schubert (1826)

- Robert Schumann (1841)

- Niels Gade (1843)

- Johannes Brahms (1855-76)

- Antonin Dvořák (1865)

- Anton Bruckner (1866)

- Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky (1872)

- Gustav Mahler (1884-1910)

- Sergei Rachmaninoff (1906-07)

- Ralph Vaughan Williams (1909-1957)

- Carl Nielsen (1916)

- Howard Hanson (1922)

- Arnold Bax (1922)

- Alan Hovhaness (1936)

- Samuel Barber (1936)

- Dmitri Shostakovich (1941)

- Arthur Honegger (1942)

- Bohuslav Martinů (1942)

- Aaron Copland (1946)

- Vagn Holmboe (1950)

- Allan Pettersson (1951-1979)

- Henryk Górecki (1959-1976)

- Robert Simpson (1962)

- Roger Sessions (1967)

- Peter Maxwell Davies (1976-2013)

- John Harbison (1981-2011)

- Ellen Taaffe Zwilich (1993)

- Christopher Rouse (1986-2019)

- Compilation of modern symphonies

In music, especially in jazz and its offshoots, evolution occurs in day-to-day expression.

- Söndörgő, “XXX” (2025) (49’): “Marking the start of the group’s fourth decade, the (first) track offers both a reflection on their musical journey and a clear signal of their continued evolution as prominent voices in Southern Slavic string traditions, approached with a distinctly contemporary sensibility.”

Albums:

- Matana Roberts, “The Truth” (2023) (37’) “follows a clear evolutionary logic. At first, the suite is arranged in blues-based scales and a retro lounge vibe, all smoke and louche phrasing. Roberts’ saxophone floats over simple, relaxing phrases from Thomas. Yet even before the first, seven-minute part is up, the tension starts to mount. Roberts gradually adds sheets of sound to increasingly complex runs as Thomas’ chords start to jump further apart, culminating in both of them suddenly bursting into frenzies of free jazz.”

- Jim Sutherland, “When Fish Begin to Crawl” (2025) (64’): “The music creates patterns in the apparently random chaos of nature to evoke the changing qualities of light on the Caithness landscape, and the tidal currents of the Pentland Firth that flow between the Atlantic Ocean and the North Sea, or the sound of a curlew carried in the wind across the dhu lochans of the flow country.”

Music: songs and other short pieces

- Ayreon, “Unnatural Selection” (lyrics)

- Pearl Jam, “Do the Evolution” (lyrics)

- David Bowie, “Changes” (lyrics)

Visual Arts

- M.C. Escher, Metamorphosis III (1967-68)

- Octavio Ocampo, The Evolution of Man

- Georgia O'Keeffe, Apple Family II

Film and Stage

- Inherit the Wind, a masterpiece about the Scopes trial; the film is packed with important personal and social themes but the intellectual combat over the subject of evolution provides the most gripping moments

- Mon Oncle D’Amerique, a comedy about understanding people through evolution and neuroscience

- Pickpocket: this “character study of a cocky young criminal who becomes so entranced by the act of picking pockets that he literally can't stop himself” illustrates the principle of social evolution on the individual level