We further empower ourselves by identifying our goals clearly, and focusing on them.

People may have goals but if they are scattered in their intention, those goals will be harder to realize. Keeping one’s eye on the prize refers to focusing on one’s dreams, or goals.

Real

True Narratives

- Juan Williams, Eyes on the Prize: America's Civil Rights Years, 1954-1965 (Viking Penguin, 1987).

- Vincent Harding, et. al., The Eyes on the Prize Civil Rights Reader: Documents, Speeches, and First Hand Accounts From The Black Freedom Struggle, 1954-1990 (Viking, 1991).

- Toby Kleban Levine, et. al., eds., Eyes on the prize: America's civil rights years: a reader and guide (Penguin, 1991).

Technical and Analytical Readings

Photographs

Documentary and Educational Films

Imaginary

Fictional Narratives

Poetry

And so we lift our gaze, not to what stands between us, but what stands before us.

[from Amanda Gorman, “The Hill We Climb”]

Music: Composers, artists, and major works

Frederic Rzewski’s magnum opus for solo piano, 36 Variations on “The People United Will Never Be Defeated” (1975) (approx. 57-64’) (list of recorded performances), could easily be placed under “Unity” or “Strength,” because its pervasive attitude, expressed, through the solo voice, conveys the idea of strength through unity. It could also be placed under democracy, or human rights. I have chosen this work to represent the virtue of remaining vigilant and focused on a cherished goal or ideal. The work is a set of variations on a simple, hummable theme. “Rzewski was a strong advocate for the Chilean people during the oppressed times of the 1960's. Rzewski wrote this piano collection as a revolutionary anthem in response to Allende coming into power in 1969. Though Rzewski was a prominent figure in the avant-garde movement, this composition allowed him to step outside of the complexities of modernism and write accessible music for a specific purpose.” “In the aftermath of the military coup that deposed Allende, the song became a call to action for the resistance in Chile, and soon spread around the world. It has been recorded, paraphrased, and sampled in many forms and languages, by artists ranging from jazz bassist Charlie Haden to Thievery Corporation and Big Sean in the U.S. alone; still current, it was sung in Cantonese by the protesters in Hong Kong . . .” “. . . the real power . . . is not the song, arresting ear-worm that it contains, but its logic. A listener knowing neither the song nor its context is faced with a classic series of variations on a theme, realized through an abstract classical construction.” Because the theme remains prominent and so easily identifiable throughout the work, this composition best represents the virtue of keeping eyes on the prize. Top recorded performances are by Ursula Oppens in 1976, Yuji Takahashi in 1978, Frederic Rzewski in 1986, Frederic Rzewski in 1991, Ralph van Raat in 2008, Kai Schumacher in 2009, Ole Kiilerich in 2012, Corey Hamm in 2014, Igor Levit in 2015, Stephen Drury in 2017, Nuss in 2022, and Vadym Kholodenko in 2022.

- Johannes Brahms, 16 Variations on a Theme by Schumann, Op. 9 (1854) (approx. 18-19’) (list of recorded performances): “What’s unusual about this theme is that it’s in the minor. . .” This probably expresses Brahms’ view of Schumann’s mental decline. Here is a link to Schumann’s theme.

- Brahms, 10 Variations on a Theme by Robert Schumann for Piano Four Hands, Op. 23 (1861) (approx. 10-16’) (list of recorded performances): “Known as Schumann’s 'last musical thought,' the composer sketched it in February 1854, saying that the E-flat melody was dictated to him by angels . . .”

- Brahms, 28 Variations on a Theme by Paganini, Op. 35 (1863) (approx. 13-17’) (list of recorded performances): “The familiar theme is played in octaves, with decorations.” As you can hear, Paganini loaded his Caprice No. 24 with variations.

- Johannes Brahms, Variations on an Original Theme No. 1, Op. 21, No. 1 (1857) (approx. 16-18’) (list of recorded performances): “Most of its duration occupies an inward, searching space . . .”

In any work of theme and variations, the idée fixe (fixed idea) is the core.

- Gabriel Fauré, Theme and Variations in C-sharp Minor, Op. 73 (1895) (approx. 14-17’) (list of recorded performances): “Fauré switches to the major mode for his final variation which looks sparse on the page but is one of the most intense things he ever wrote. . . As Robert Orledge writes in his excellent biography of the composer: ‘It raises the whole work onto a higher, almost religious plane … the chorale rises from its serenity to a climax of transcendental intensity, making the flashy excitement of the penultimate variation seem trivial in comparison.’”

- Amy Beach, Theme and Variations for Flute and String Quartet, Op. 80 (1916) (approx. 21’) (list of recorded performances): The theme was Beach’s own “Indian Lullaby”.

- Benjamin Britten, Variations on a Theme of Frank Bridge, for string orchestra, Op. 10 (1937) (approx. 24-29’) (list of recorded performances), “is the composer’s musical tribute to his teacher.” Here is a link to Bridge’s theme.

- Paul Dukas, Variations, Interlude and Finale on a Theme by Rameau (1902) (approx. 15-18’) (list of recorded performances): “Dukas chooses a theme of disarming simplicity from Rameau. Then he applies some of his own views . . .”

- Louis Moyse, Introduction, Theme and Variations, for flute and piano (1980) (approx. 20’)

- Carl Nielsen, Prelude, Theme and Variations for solo violin, Op. 48, FS 104 (1923) (approx. 14-17’) (list of recorded performances)

- Miklós Rózsa, Theme, Variations and Finale, Op. 13 (1933) (approx. 17-19’): “The initial idea, a melancholy oboe theme, came to Rózsa as he was leaving Budapest by boat to settle in Paris. He had made fond farewells to his family and it was the last time he would ever see his father.”

- Franz Schubert, Introduction and Variations on Trockne Blumen, Op. posth. 160, D. 802 (1824) (approx. 16-21’) (list of recorded performances), “uses the 18th song from Die schöne Müllerin (‘Trockne Blumen’) as the basis for a set of variations.” Here is a link to “Trockne Blumen”.

- Igor Shostakovich, Theme and Variations in B-flat Major, Op. 3 (1922) (approx. 15-16’) (list of recorded performances)

- Charles Stanford, Concert Variations Upon an English Theme "Down Among the Dead Men" for piano and orchestra in C Minor, Op. 71 (1898) (approx. 26-27’)

- Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, Variations on a Rococo Theme for Cello & Orchestra, Op. 33, TH 57 (1877) (approx. 19-22’) (list of recorded performances) (arr. for flugelhorn), “were dedicated to the cellist Karl Friedrich Wilhelm Fitzenhagen . . .”

- William Walton, Variations on a Theme by Hindemith (1963) (approx. 23-25’) (list of recorded performances): “The theme comes from the opening passage, including harmony, of the slow movement of Hindemith’s 1940 cello concerto.” Here is link to Hindemith’s concerto.

- Paul Paray, Theme et Variations, for piano (1913) (approx. 12’)

- Antoine Edouard Pratté (Anton Edvard Pratté), Theme and Variations on a Swedish Folk Tune (1800s) (approx. 12’)

- Ludwig van Beethoven, 32 Variations on an Original Theme in C Minor, WoO 80 (1806) (approx. 10-12‘) (list of recorded performances)

- Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, 8 Variations in A Major on “Come un agnello”, K. 460 (1784) (approx. 13-14’) (list of recorded performances)

In three compositions, Max Reger added a twist, with a fugue (wandering).

- Variations and Fugue on a Theme by Bach for Piano, Op. 81 (1904) (approx. 30-35’) (list of recorded performances): The theme is taken from 4th movement aria (duet) of Cantata Auf Christi Himmelfahrt allein, BWV 128.

- Variations and Fugue on a Theme by Johann Adam Hiller, in E Major, Op. 100 (1907) (approx. 41-45’) (list of recorded performances)

- Variations and Fugue on a theme by Telemann for Piano, Op. 134 (1914) (approx. 31’) (list of recorded performances)

Other compositions:

- Howard Hanson, Piano Concerto in G Major, Op. 36 (1948) (approx. 20’) (list of recorded performances): a strong idée fixe is prominent in this work.

- Shostakovich, String Quartet No. 9 in E-flat Major, Op. 117 (1964) (approx. 26-29’) (list of recorded performances): the second violin establishes the basic idea, which remains prominent throughout each movement.

Music: songs and other short pieces

- Sung-bong Choi on Korea’s Got Talent, and in the competition final

- Rising Appalachia, Resilient

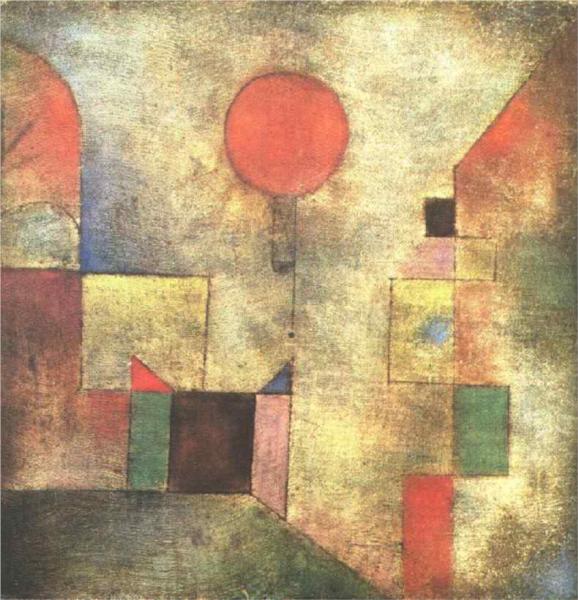

Visual Arts

Film and Stage

On the shadow side:

- The Bridge on the River Kwai, about an army colonel who lost sight of the prize.