Speaking directly and without reservation, without being overly aggressive or intimidating, is an important social skill.

- I am not intimidating, I am forthright! [attributed to Deborah Meaden]

- The way you build trust with your people is by being forthright and clear with them from day one. You may think people are fooled when you tell them what they want to hear. They are not fooled. [attributed to Dick Costolo]

- There’s a certain logic to systems, and that logic is fairly self-evident. It’s very straightforward, usually. It might take a little research, it might take a little bit of industry to prize it out, but it’s there to be seen. [attributed to Michael Nesmith]

Forthrightness is another value that runs head-on into humility. Still, there is a value in speaking directly and honestly. We can explore the parameters and potential resolutions of this and other conflicts through our narratives, true and fictional.

Real

True Narratives

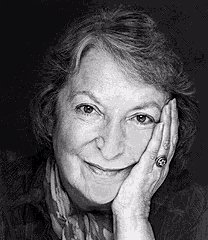

Pauline Kael's "'lack of introspection, self-awareness, restraint or hesitation' . . . gave her 'supreme freedom to speak up, to speak her mind, to find her honest voice'" as a film critic.

- Brian Kellow, Pauline Kael: A Life in the Dark (Viking, 2011).

- Sanford Schwartz, ed., The Age of Movies: Selected Writings of Pauline Kael (The Library of America, 2011).

- Francis Davis, Afterglow: A Last Conversation with Pauline Kael (Da Capo Press, 2002).

- Will Brantley, ed., Conversations with Pauline Kael (University Press of Mississippi, 1996).

- Pauline Kael, For Keeps: 30 Years at the Movies (Dutton Adult, 1994).

- Pauline Kael, 5001 Nights at the Movies (Henry Holt & Company, 1991).

Many journalists exemplify the value of being forthright:

- Art Cullen, Storm Lake: A Chronicle of Change, Resilience, and Hope from a Heartland Newspaper (Viking, 2018): “As Cullen writes in his new book, ‘Storm Lake,’ when he and his brother John began to publish their newspaper, they had one thing in mind: ‘Print the truth and raise hell.’”

- Lesley M.M. Blume, Fallout: The Hiroshima Cover-up and the Reporter Who Revealed It to the World (Simon & Schuster, 2020): “On Aug. 31, 1946, when The New Yorker published John Hersey’s 'Hiroshima,' the 30,000-word article’s impact was instantaneous and global.”

Memoirs:

- Vanessa Springora, Consent: A Memoir (HarperVia/HarperCollins Publishers, 2021): “. . . a Molotov cocktail, flung at the face of the French establishment, a work of dazzling, highly controlled fury.”

Technical and Analytical Readings

Photographs

Documentary and Educational Films

Imaginary

Fictional Narratives

“You seem to wonder; but if you will get me fairly at it, I’ll make a clean breast of it. This cursed business, accursed of God and man, what is it? Strip it of all its ornament, run it down to the root and nucleus of the whole, and what is it? Why, because my brother Quashy is ignorant and weak, and I am intelligent and strong,—because I know how, and can do it,—therefore, I may steal all he has, keep it, and give him only such and so much as suits my fancy. Whatever is too hard, too dirty, too disagreeable, for me, I may set Quashy to doing. Because I don’t like work, Quashy shall work. Because the sun burns me, Quashy shall stay in the sun. Quashy shall earn the money, and I will spend it. Quashy shall lie down in every puddle, that I may walk over dry-shod. Quashy shall do my will, and not his, all the days of his mortal life, and have such chance of getting to heaven, at last, as I find convenient. This I take to be about what slavery is. I defy anybody on earth to read our slave-code, as it stands in our law-books, and make anything else of it. Talk of the abuses of slavery! Humbug! The thing itself is the essence of all abuse! And the only reason why the land don’t sink under it, like Sodom and Gomorrah, is because it is used in a way infinitely better than it is. For pity’s sake, for shame’s sake, because we are men born of women, and not savage beasts, many of us do not, and dare not, — we would scorn to use the full power which our savage laws put into our hands. And he who goes the furthest, and does the worst, only uses within limits the power that the law gives him.” [Harriett Beecher Stowe, Uncle Tom’s Cabin or Life Among the Lowly (1852), Volume II, Chapter XIX, “Miss Ophelia’s Experiences and Opinions Continued”.]

Winner of the 2013 Nobel Prize in literature, Alice Munro is a starkly honest master of the short story.

- Alice Munro, Hateship, Friendship, Courtship, Loveship, Marriage (Thorndike Press, 2002).

- Alice Munro, Emily of the New Moon (New Candian Library, 2007).

- Alice Munro, Something I’ve Been Meaning to Tell You (Random House, 1974).

- Alice Munro, Runaway: Stories (Alfred A. Knopf, 2004).

- Alice Munro, Dear Life: Stories (Alfred A. Knopf, 2012).

- Alice Munro, Dance of the Happy Shades and Other Stories (McGraw Hill, 1973).

- Alice Munro, Friend of My Youth: Stories (Alfred A. Knopf, 1990).

- Alice Munro, The Beggar Maid: Stories of Flo and Rose (Random House, 1978).

- Alice Munro, The Moons of Jupiter: Stories (Alfred A. Knopf, 1982).

- Alice Munro, The Progress of Love: Stories (Alfred A. Knopf, 1986).

- Alice Munro, Open Secrets: Stories (Alfred A. Knopf, 1994).

- Alice Munro, The Love of a Good Woman: Stories (Alfred A. Knopf, 1998).

Novels and stories:

- Garth Risk Hallberg, The Uncollected Stories of Mavis Gallant (New York Review of Books, 2025): “. . . short stories full of brutal humor that examined the hell of other people.”

Poetry

I was not beloved of the villagers,

But all because I spoke my mind,

And met those who transgressed against me

With plain remonstrance, hiding nor nurturing

Nor secret griefs nor grudges.

That act of the Spartan boy is greatly praised,

Who hid the wolf under his cloak,

Letting it devour him, uncomplainingly.

It is braver, I think, to snatch the wolf forth

And fight him openly, even in the street,

Amid dust and howls of pain.

The tongue may be an unruly member—

But silence poisons the soul.

Berate me who will—I am content.

[Edgar Lee Masters, “Dorcas Gustine”]

Other poems:

- Edgar Lee Masters, “Voltaire Johnson”

Music: Composers, artists, and major works

Ludwig van Beethoven, String Quartet No. 11 in F minor, “Serioso”, Op. 95 (1810) (approx. 21-22’): though Beethoven’s briefest string quartet, it is also quite intense. We could say that Beethoven got right to the point.

Sergei Prokofiev’s compositional style can aptly be described as quirky. Laced with wit and humor, his music evokes the difficulties and absurdities of social life in his native Russia, and in the Soviet Union of his time. Superficially, Prokofiev’s music seems to take a round-about approach but once the listener understands the humor, the message is clear.

- Piano Concerto No. 1 in D-flat Major, Op. 10 (1912) (approx. 14-17’)

- Piano Concerto No. 2 in G minor, Op. 16 (1923) (approx.30-34’)

- Piano Concerto No. 3 in C Major, Op. 26 (1921) (approx.27-33’)

- Piano Concerto No. 4 in B flat Major, for the left hand, Op. 53 (1931) (approx. 24-27’)

- Piano Concerto No. 5 in G Major, Op. 55 (1932) (approx. 22-25’)

- Piano Sonata No. 1 in F minor, Op. 1 (1909) (approx. 8’)

- Piano Sonata No. 2 in D minor, Op. 14 (1912) (approx. 17-19’)

- Piano Sonata No. 3 in A minor, Op. 28 (1917) (approx. 7-8’)

- Piano Sonata No. 4 in C minor, Op. 29 (1917) (approx. 17-18’)

- Piano Sonata No. 5 in C Major, Op. 38 (1923, rev. 1953) (approx. 15-16’)

- Piano Sonata No. 6 in A Major, Op. 82 (1940) (approx. 25-28’)

- Piano Sonata No. 7 in B-flat Major, Op. 83, “Stalingrad” (1942) (approx. 19’)

- Piano Sonata No. 8 in B-flat Major, Op. 84 (1944) (approx. 29-33’)

- Piano Sonata No. 9 in C Major, Op. 103 (1947) (approx. 23-29’)

- Visions Fugitives, Op. 22 (1917) (approx. 20-23’)

- Sarcasms, Op. 17 (1914) (approx. 10-12’)

Domenico Scarlatti’s 555 keyboard sonatas are crisply constructed little works, approximately five to fifteen minutes in duration. In them, Scarlatti presents simple musical ideas, to be executed with dispatch. Though their brevity leaves little time for thematic development, Scarlatti left us with a collection of works in these sonatas that laid the groundwork for later developments in the form, and simultaneously was fine music on its own. Here are links to performances of all 555 sonatas by Scott Ross on harpsichord, and of selected sonatas performed by Kipnis, and on piano by Pogorelić, Schmitt-Leonardy and Gould. Many others are available.

Other works:

- Malcolm Arnold, Clarinet Concerto No. 1, Op. 20 (1948) (approx. 16-19’), is “terse” and to the point.

- Yannis A. Papaïoannou’s 24 Preludes for Piano – perf. Katsaris: “. . . one of the delights of this music is its concision.”

- Gabriel Fauré, Piano Quartet No. 1 in C Minor, Op. 15 (1879) (approx. 29-32’): many musicologists suspect that Fauré composed in deliberate counterpoint to Wagner’s bluster. The work “inhabits a magical world of shimmering colors and buoyant, effortless motion. Amid the emotional excesses of nineteenth century Romanticism, this is music made up of pristine lines and classical elegance. It unfolds with a sublime simplicity and directness. Its expression arises from a kind of emotional detachment.”

- Béla Bartók, String Quartet No. 4, “Metamorphoses Nocturnes”, Sz. 91, BB 95, Op. 7 (1928) (approx. 28-31’): “Taut, economical, almost geometrical in its arguments, it is music that wastes not a single note, and thus conveys a kind of athletic exuberance.”

Known as “the middleweight champion of the tenor saxophone”, Hank Mobley occupied a middle ground between aggressiveness and gentility. On his albums, his saxophone is front-and-center, expressing the music with straightforward clarity, but never overpowering the ensemble. He recorded many albums, from 1955-1970.

Alex Sipiagin is a jazz trumpeter with a deceptively simple musical style. He executes difficult runs so easily that the difficulty goes unnoticed. His tonal clarity is impeccable. One could aptly say that he just plays, albeit with great skill. Here he is with his sextet at Dizzy’s in Lincoln Center in 2018; and at Miami Dade College. Here is a link to his playlists.

Eric Alexander is an excellent jazz saxophonist who plays engaging straight-ahead jazz. Here is a link to his playlists.

Other albums:

- Ronnie Cuber, “Straight Street” (2019) (71’)

- Larry Goldings, Peter Bernstein & Bill Stewart, “Perpetual Pendulum” (2022) (65’) is an example of straightforward playing that isn’t abrasive or showy – the musicians let the music speak for itself.

- Paul Booth, “44” (2022) (54’): “Forthright, forthcoming, there’s a fortune of talent here.”

- Jon Lloyd Quartet, “Earth Songs” (2024) (69’) “offers straightforwardly memorable tunes: caressed, never bullied with technique. Each contributes to a mood of patient exploration as beguiling as it is beautiful.” This album illustrates the point that straightforwardness can be gentle, not harsh.

- Sunny Five, “Candid” (2024) (72’): “Sunny Five with Tim Berne, David Torn, Marc Ducret, Devin Hoff and Ches Smith brings together five of the most prominent voices on the New York jazz scene. This group of friends pursues a creative vision that explores the juxtaposition of pure acoustic sonic elements and the integration of electric/electronic sound-generation.”

- Emel Mathlouthi, “MRA” (2024) (43’): “MRA is exciting on musical and cultural levels; Emel features artists who are often overlooked by virtue of gender or origin and, with them, dabbles in dramatic flavors of rock, EDM, and roots music from many different places themselves. This is what contemporary pop should be: a true and socially conscious mélange that makes its audiences want to listen, learn, and move.”

Music: songs and other short pieces

Visual Arts

- Kazimir Malevich, Suprematist Composition: White on White (1917)

Film and Stage

- King Lear, Shakespeare’s cautionary tale about a father who unwisely chooses false flattery

- Ran, Kurosawa’s brilliant adaptation of “King Lear”

- The Mortal Storm: a blunt assessment of Nazi Germany before American entry into World War II

- Diary of a Chambermaid, a social criticism

- Amélie, a study in being too coy

- Sitting Pretty, about a brutally honest caretaker