Basic goodness and decency are foundational in life and ethics.

- Doing Good is a simple and universal vision. A vision to which each and every one of us can connect and contribute to its realisation. A vision based on the belief that by doing good deeds, positive thinking and affirmative choice of words, feelings and actions, we can enhance goodness in the world. [Shari Arison]

- We have a duty to show up in the world with meaning and purpose and commitment to doing good. And to use any privilege that we have to make positive change and to disrupt oppressive systems. [attributed to Meena Harris]

- When the norm is decency, other virtues can thrive: integrity, honesty, compassion, kindness, and trust. [attributed to Raja Krishnamoorthi]

***

I am one who believes that human happiness and well-being depend on people and societies advancing beyond what we might call the contract level of human interaction. If life was perfectly predictable and every contract, or agreement, was crystal clear, we might be able to achieve a just society through merely contractual arrangements. But because life is messy, we need more than merely abiding by our formal agreements. We need an ethic of loving kindness and generosity, which we might call by the composite term “goodness.”

Real

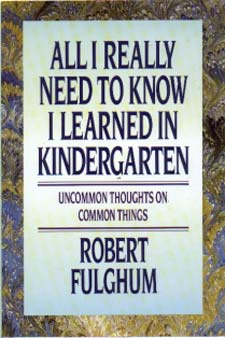

True Narratives

Technical and Analytical Readings

Photographs

Documentary and Educational Films

Imaginary

Fictional Narratives

Jean Prouvaire was a still softer shade than Combeferre. His name was Jehan, owing to that petty momentary freak which mingled with the powerful and profound movement whence sprang the very essential study of the Middle Ages. Jean Prouvaire was in love; he cultivated a pot of flowers, played on the flute, made verses, loved the people, pitied woman, wept over the child, confounded God and the future in the same confidence, and blamed the Revolution for having caused the fall of a royal head, that of André Chénier. His voice was ordinarily delicate, but suddenly grew manly. He was learned even to erudition, and almost an Orientalist. Above all, he was good; and, a very simple thing to those who know how nearly goodness borders on grandeur, in the matter of poetry, he preferred the immense. He knew Italian, Latin, Greek, and Hebrew; and these served him only for the perusal of four poets: Dante, Juvenal, Æschylus, and Isaiah. In French, he preferred Corneille to Racine, and Agrippa d'Aubigné to Corneille. He loved to saunter through fields of wild oats and corn-flowers, and busied himself with clouds nearly as much as with events. His mind had two attitudes, one on the side towards man, the other on that towards God; he studied or he contemplated. All day long, he buried himself in social questions, salary, capital, credit, marriage, religion, liberty of thought, education, penal servitude, poverty, association, property, production and sharing, the enigma of this lower world which covers the human ant-hill with darkness; and at night, he gazed upon the planets, those enormous beings. Like Enjolras, he was wealthy and an only son. He spoke softly, bowed his head, lowered his eyes, smiled with embarrassment, dressed badly, had an awkward air, blushed at a mere nothing, and was very timid. Yet he was intrepid. [Victor Hugo, Les Misérables (1862), Volume III – Marius; Book Fourth – The Friends of the A B C, Chapter I, “A Group which barely missed becoming Historic”.]

Narratives, from the dark side:

- There is practically nothing good or decent about the characters’ behavior in Shakespeare’s tragedy “Cymbeline”. Everyone’s behavior is transactional and self-serving. “King Cymbeline of Britain banishes his daughter Innogen's husband, who then makes a bet on Innogen's fidelity. Innogen is accused of being unfaithful, runs away, and becomes a page for the Roman army as it invades Britain. In the end, Innogen clears her name, discovers her long-lost brothers and reunites with her husband while Cymbeline makes peace with Rome.”

Poetry

Music: Composers, artists, and major works

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Piano Sonatas (1773-1788) (approx. 340-390’) (list of recorded performances) are relatively simple works, in Mozart’s characteristically sunny tone. Excellent recorded performances of the complete or nearly complete sonatas are by Klara Würtz, Mitsuko Uchida, Lili Kraus, Claudio Arrau, Walter Gieseking, and Robert Levin.

- Piano Sonata No. 1 in C Major, K. 279 (1774) (approx. 12-14’) (list of recorded performances)

- Piano Sonata No. 2 in F Major, K. 280 (1774) (approx. 10’) (list of recorded performances)

- Piano Sonata No. 3 in B-flat Major, K. 281 (1774) (approx. 11-15’) (list of recorded performances)

- Piano Sonata No. 4 in E-flat Major, K. 282 (1774) (approx. 15-16’) (list of recorded performances)

- Piano Sonata No. 5 in G Major, K. 283 (1774) (approx. 12-14’) (list of recorded performances)

- Piano Sonata No. 6 in D Major, K. 284, “Dürnitz” (1775) (approx. 22-30’) (list of recorded performances)

- Piano Sonata No. 7 in C Major, K. 309 (1777) (approx. 16-20’) (list of recorded performances)

- Piano Sonata No. 8 in A minor, K. 310 (1778) (approx. 19-22’) (list of recorded performances)

- Piano Sonata No. 9 in D Major, K. 311 (1778) (approx. 14-20’) (list of recorded performances)

- Piano Sonata No. 10 in C Major, K. 330 (1783) (approx. 20-22’) (list of recorded performances)

- Piano Sonata No. 11 in A Major, K. 331, “Alla Turca” (1783) (approx. 22-24’) (list of recorded performances)

- Piano Sonata No. 12 in F Major, K. 332 (1783) (approx. 19-24’) (list of recorded performances)

- Piano Sonata No. 13 in B-flat Major, K. 333 (1783) (approx. 19-20’) (list of recorded performances)

- Piano Sonata No. 14 in C minor, K. 457 (1784) (approx. 20-22’) (list of recorded performances)

- Piano Sonata No. 15 in F Major, K. 533 (1788) (approx. 23-25’) (list of recorded performances)

- Piano Sonata No. 16 in C Major, K 545, “Facile” (1788) (approx. 12-14’) (list of recorded performances)

- Piano Sonata No. 17 in B-flat Major, K. 570 (1789) (approx. 16-18’) (list of recorded performances)

- Piano Sonata No. 18 in D Major, K. 576, “Hunt” (1789) (approx. 14’) (list of recorded performances)

Jean-Marie Leclair, violin (some flute) concerti are similar in tone to Mozart’s Piano Sonatas – not deep but affirmative in spirit:

- Op. 7 (1737 or before) (list of recorded performances): No. 1 in D minor (approx. 14’) (list of recorded performances); No. 2 in D Major (approx. 16’) (list of recorded performances); No. 3 in C Major (approx. 14’) (list of recorded performances); No. 4 in F Major (approx. 14’) (list of recorded performances); No. 5 in A minor (approx. 14’) (list of recorded performances); No. 6 in A Major (approx. 22’) (list of recorded performances).

- Op. 10 (1740s): No. 1 in B-flat major (approx. 13’) (list of recorded performances); No. 2 in A Major (approx. 15’) (list of recorded performances); No. 3 in D Major (approx. 17’) (list of recorded performances); No. 4 in F Major (approx. 15’) (list of recorded performances); No. 5 in E minor (approx. 16’) (list of recorded performances); No. 6 in G minor (approx. 18’) (list of recorded performances).

John Jenkins was a Baroque-era composer whose works reflect sincerity and empathy. This is apparent on the following albums of his music:

- Fretwork, “Division: John Jenkins - The Virtuoso Consort” (2025) (78’)

- The Consort of Musicke, “John Jenkins - Consort Music” (1983) (70’)

- Phantasm, “John Jenkins - Four-Part Consorts” (2022) (76’)

- The Parley of Instruments, “John Jenkins: Late Consort Music” (1992) (60’)

Other compositions:

- Mozart, Lucio Silla, K. 135 (1772) (approx. 146-154’) (libretto) (list of recorded performances): in the end, virtue triumphs over power as the dictator relents and allows the lovers to marry. Mozart composed the opera when he was only sixteen years old. Recorded performances feature Schreier, Gruberova, Bartoli, Upshaw & Kenny (Harnoncourt) in 1990; and Odinius, Nold, Hammarström & Bonde-Hansen.

- Louis Karchin, Romulus (1990, rev. 2006) (approx. 71’) is based on Dumas’ 1854 theatrical comedy “Romulus”. The protagonists, a philosopher and an astronomer, are decent and sincere. “The story is a gentle farce, featuring two absent-minded bachelors, one a philosopher (Wolf), the other an astronomer (Celestus), their housekeeper Martha (Celestus’s sister), and a bumbling busybody of a mayor (Babelhausen). The appearance of a baby in a basket upsets their household, and suspicions of paternity almost wreck their carefully constructed relationships, until something of a deus ex machina revelation (albeit well-enough prepared) allows everything to be corrected, and the characters can move to a higher level of love and maturity.”

- Carl Maria von Weber, Flute Trio in G Minor, J 259, Op. 63 (1819) (approx. 23-24’) (list of recorded performances): “Despite being in a minor key, this is sunny music, filled with charm and lightness more than anything else.”

- Friedrich Witt, Symphony No. 14 in C Major, “Jena” (ca. 1793) (approx. 26’) “has been described as ‘a splendid example of symphonic writing from a time when this form was achieving both prestige and popularity with a growing music-loving public.'”

- Witt, Symphony in A Major (c. 1785) (approx. 22’)

- Fortunato Chelleri, 6 Sonate di Gallanteria (ca. 1730) (approx. 71’)

- Wenzel Thomas Matiegka (Václav Tomáš Matějka), 6 Sonatas for Guitar, Op. 31 (approx. 75’) are simple, straightforward and unassuming.

- Thomas Haigh, Harpsichord Concertos: There are no masterpieces here, only joyful harpsichord music from the classical period in Britain.

Albums:

- Nigel Price & Alban Claret, “Entente Cordiale” (2023) (61’): “The two guitarists’ styles are well suited to each other throughout, speaking the same language with slightly different inflections and accents. The name of the album — translated as a cordial agreement with — is playful in that these musicians play as if they were born in agreement.”

- Eric Bibb, “In the Real World” (2024) (55’): “. . . his mellow delivery belies his somber messages for change and redemption. Bibb is a preacher, but not a pulpit-pounder. He gets his point across sliding all that heavy stuff right underneath his wings and still lifting off smoothly.”

- Margherita Torretta, “Elisabetta De Gambarini: Complete Works for Keyboard” (2024) (56’): congenial piano music, from a woman of the 18th century

From the dark side:

- Lyander Piano Trio, “Mirrors” album (2020) (71’) “reflects upon 21st century music”.

- Charles Fussell, Cymbeline (1985) (approx. 55’) (libretto) is crafted after Shakespeare’s play about “deceit, pursuit and seduction”.

Music: songs and other short pieces

- Tim McGraw, “Humble and Kind” (lyrics)