When the emotions have us fully immersed in life, and all it has to offer, doors open.

- You don’t say to a university professor who is immersed in a particular subject that they should get a life. They are encouraged to enjoy their subject and to pass it on. [attributed to Magnus Magnusson]

- A reader is not supposed to be aware that someone’s written the story. He’s supposed to be completely immersed, submerged in the environment. [attributed to Jack Vance]

- Heaven to me is percussion and bass, a screaming guitar and a burbling Hammond B-3 organ. It’s a soup I love being immersed in. [attributed to Dan Aykroyd]

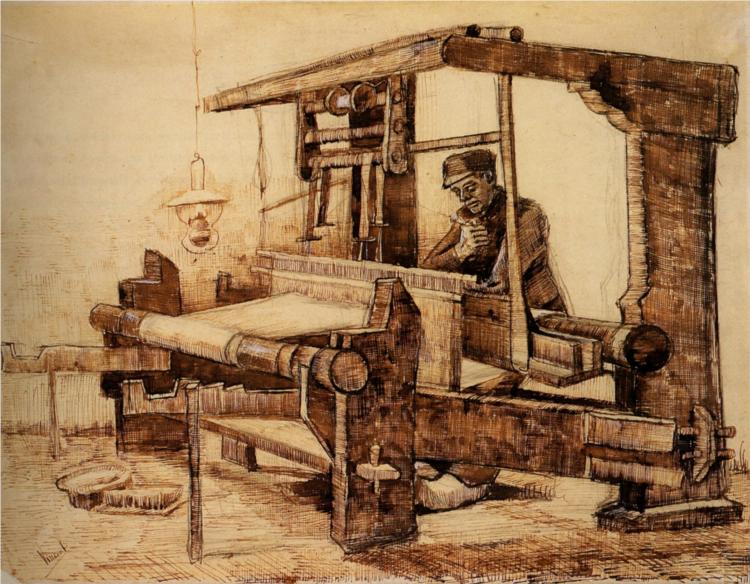

In van Gogh’s painting “Weaver”: “The confining structure of the large loom displays the weaver fully absorbed in his task, reflecting a parallel intensity van Gogh sensed in his own endeavors.“

Beyond mere interest is emotional involvement. This does not mean being emotionally consumed or debilitated; it means energized and eager.

When we are emotionally involved in something, we are more likely to be fully engaged in it. We may go so far as to immerse ourselves in it. That level of involvement represents excellence in the emotional domain.

Involvement can have beneficial effects on others too. In fundamental ways, emotional involvement of parents and caregivers is essential to childrens’ growth and development. “Infants are immersed in a world of mutual responsiveness within caring relationships that are infused with concern, interest, and enjoyment. In such a developmental system, infants become persons when they are treated as persons.” Parental emotional involvement positively affects middle and high school students. Emotional engagement of caregivers and significant others is important in responding to Huntington’s Disease (decay of brain cells over time).

Real

True Narratives

Gertrude Bell was "an extraordinary British diplomat and spy." As a youth, she immersed herself in "doing things young girls don’t normally do, such as Alpine mountaineering and desert archaeology." After losing the only love of her life to war, she immersed herself in Mesopotamian culture and political affairs, and is widely credited with establishing modern Iraq. Though the ethical dimension of aiding imperial Britain's drive to create a monarchy in a foreign land is dubious to say the least, Bell's work merits inclusion in our narrative as an example of excellence in involvement: like the weaver at van Gogh's loom, Gertrude Bell immersed herself in her chosen endeavor.

- Gertrude Bell, The Arabian Diaries, 1913-1914 (Syracuse University Press, 2000).

- Gertrude Bell, Syria: The Desert and the Sown (William Heinemann Ltd., 1907).

- Gertrude Bell, Iraq and Gertrude Bell's The Arab of Mesopotamia The Arab of Mesopotamia (Lexington Books, 2008).

- Gertrude Bell, Letters: Volume 1 (Boni & Liveright, 1927); Volume 2 (Boni & Liveright, 1927).

- Georgina Howell, Gertrude Bell: Queen of the Desert, Shaper of Nations (Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2007).

- Janet Wallach, Desert Queen: The Extraordinary Life of Gertrude Bell: Adventurer, Adviser to Kings, Ally of Lawrence of Arabia (Nan A. Talese, 1996).

- H.V.F. Winstone, Gertrude Bell: A Biography (Jonathan Cape, 1978).

Other people who lived immersed in life:

- Anna von Planta, ed., Patricia Highsmith: Her Diaries and Notebooks (Liveright, 2021): “Patricia Highsmith Lived Extravagantly, and Took Copious Notes”.

- Sutton Foster, Hooked: How Crafting Saved My Life (Grand Central Publishing, 2021): “In those moments where she knitted or drew or stitched, Foster was free from the worry of the world’s judgment; she could relax or celebrate or — as in the case of the granny square blanket replete with owls — mourn for her mother as she was dying.”

- Natalie Livingstone, The Women of Rothschild: The Untold Story of the. World’s Most Famous Dynasty (St. Martin’s Press, 2022), “focuses on several generations of the banking family’s wives and daughters, documenting their passions for politics, science and music, all abetted by wealth and social connections”.

Technical and Analytical Readings

Photographs

Documentary and Educational Films

Imaginary

Fictional Narratives

Novels:

- Juli Delgado Lopero, Fiebre Tropical: A Novel (The Feminist Press, 2020): “What this novel is about, even more than acculturation, is observing women.”

- An Yu, Ghost Music: A Novel (Grove Press, 2023), “is an evocative exploration of what it means to live fully — and the potential consequences of failing to do so. Yu braids the mundane and the magical together with a gentle hand: Song Yan receives regular visitations from a giant, luminescent talking mushroom . . .”

Poetry

Music: Composers, artists, and major works

Conductor Carlos Kleiber’s musical style was intense and passionate. “Enigmatic, eccentric, great and passionate are all familiar and perhaps even alluring descriptions . . .” He was an “operatic conductor of originality and passion”. “In 2012 a BBC Poll asked 100 conductors including Sir Colin Davis, Gustavo Dudamel and Valery Gergiev to vote for their favourite conductor. Kleiber was named the greatest ahead of Bernstein and Abbado.” Curiously, though, he did not enjoy conducting, saying “I conduct only when I am hungry.” His “aesthetic was founded on the interplay between voluptuous refinement and an impulse to violence.” However, when he conducted, there was no mistaking his full engagement: “. . . Kleiber was very much in the moment, never satisfied with the status quo . . .” “This quality of looking deeper into the score, and acting upon it at a moment’s notice, put the orchestra on its toes. He projected passion and total involvement, and the orchestra wanted to reciprocate.” Charles Barber authored a biography. Kleiber is seen here in rehearsal, and in performance. Documentaries are by BBC, and Deutsche Grammophon. Here is a link to his playlists.

Antonio de Cabezón (1510-1566) was a Spanish Renaissance-era composer from Iberia. In the hands of organist Claudio Astronio (392’), at least, Cabezón’s music conveys a feeling of unfailing involvement, like the weaver in van Gogh’s drawing. With its sustained tones on organ and the music’s continuous movement from one often-complex chord to another, the listener has a sense of being led invitingly through Cabezón’s world. Perhaps this blind composer had something of that feeling himself, deprived as he was of his sight since childhood. Whether for solo organ or for organ accompanied by ensemble, Cabezón’s music does what great music should do, drawing us into a world of sound and auditory motion in which we cannot help but become involved. “. . . Cabezón was a pivotal transitional composer who freed instrumental music from its vocal predecessors. . . (He) composed works in all the instrumental forms used in Spain during the first half of the sixteenth century.” As one reviewer has remarked: “If Cabezón’s music may be said to embody any expressive characteristic, it is the somber magnificence of Spanish theater, not just literally from the stage, but from the drama embedded in its music.”

Romantic-era composer Henry Vieuxtemps’ seven violin concerti express the virtue of involvement.

- Violin Concerto No. 1 in E Major, Op. 10 (1840) (approx. 38-40’) (list of recorded performances)

- Violin Concerto No. 2 in F-sharp minor, Op. 19 (1836) (approx. 20-21’) (list of recorded performances), “makes a more classical (or post-classical) impression than a romantic one, and reveals clear signs of Vieuxtemps’s study of classical models—notably Mozart and Beethoven.”

- Violin Concerto No. 3 in A Major, Op. 25 (1844) (approx. 34-36’) (list of recorded performances)

- Violin Concerto No. 4 in D minor, Op. 31, “Grand” (1850) (approx. 23-31’) (list of recorded performances), “is a grandly imposing work in four movements, the second of which (connected to the first by a long-held horn note), Adagio religioso, convincingly shows that Vieuxtemps could not only set the strings ablaze but could also invent melodies of beguiling, sensuous warmth.”

- Violin Concerto No. 5 in A minor, "Gretry", Op. 37 (1861) (approx. 18-19) (list of recorded performances)

- Violin Concerto No. 6 in G Major, Op. 47 (1865) (approx. 26-27) (list of recorded performances)

- Violin Concerto No. 7 in A minor, “À Jenő Hubay”, Op. 49 (1870) (approx. 18’) (list of recorded performances)

A heads-up, on-your-toes quality runs throughout Bohuslav Martinů’s six symphonies.

- Symphony No. 1, H 289 (1942) (approx. 33-37’) (list of recorded performances)

- Symphony No. 2, H 295 (1943) (approx. 24-25’) (list of recorded performances)

- Symphony No. 3, H 299 (1944) (approx. 27-30’) (list of recorded performances)

- Symphony No. 4, H 305 (1945) (approx. 34-36’) (list of recorded performances), “is the most joyous of the author's six compositions of this genre. When working on the third movement, Bohuslav Martinů (1890–1959) was caught up by news of Germany's capitulation.”

- Symphony No. 5, H 310 (1946) (approx. 27-33’) (list of recorded performances)

- Symphony No. 6, H 343, “Fantaisies symphoniques” (1951) (list of recorded performances)

These string quartets by Alfred Hill do not seem to express any particular spiritual theme but they do illustrate the virtue/value of being involved. “The musical language of Alfred Hill’s string quartets is reminiscent of Dvorák and Tchaikovsky with easily remembered melodies crafted within the harmonic texture of the romantic era, rhythmic vitality in the outer movements, and consistently beautiful slow movements of much charm. The blend of antipodean nationalism with the traditional forms and musical language of late nineteenth-century Europe brings a uniqueness and freshness that has appeal on a first hearing, yet reveals a wealth of underlying ideas on further acquaintance.”

- String Quartet No. 4 in C minor, “The Pursuit of Happiness” (1916) (approx. 24’)

- String Quartet No. 5 in E-flat Major, "The Allies" (1920) (approx. 28-30’)

- String Quartet No. 6 in G Major, "The Kids" (1927) (approx. 15-16’)

- String Quartet No. 7 in A Major (1934) (approx. 20-21’)

- String Quartet No. 8 in A Major (1934) (approx. 25-26’)

- String Quartet No. 9 in A minor (1935) (approx. 23’)

- String Quartet No. 10 in E Major (1935) (approx. 20’)

- String Quartet No. 11 in D minor (1935) (approx. 18’)

- String Quartet No. 12 in E Major (1936) (approx. 21’)

- String Quartet No. 13 in E-flat Major (1936) (approx. 21’)

- String Quartet No. 14 in B minor (1951) (approx. 25’)

The string quartets of Wilhelm Stenhammar “are widely regarded as the most important written between those of Brahms and Bartók. Tonally, they range from the middle late Romantics to late Sibelius.” The composer expressed his intent: “. . . in these Arnold Schönberg times I dream of art far away from Arnold Schönberg, clear, joyful, and naive”. As a whole, these works seem to express the composer’s life experience.

- String Quartet No. 1 in C Major, Op. 2 (1894) (approx. 33’): “. . . Stenhammar slotted consciously into the Romantic Austro–German mainstream, with Brahms to the fore and Beethoven close behind.”

- String Quartet No. 2 in C minor, Op. 14 (1896) (approx. 29-32’): “. . . the composer enters more enigmatic, chromatic territory . . .”

- String Quartet in F minor (1897) (approx. 21’) is a youthful quartet, with which Stenhammar was never satisfied.

- String Quartet No. 3 in F Major, Op. 18 (1900) (approx. 28-33’) (list of recorded performances), represents the full emergence of the composer’s voice, after the comparative failure of his F minor quartet.

- String Quartet No. 4 in A minor, Op. 25 (1909) (approx. 31-36’) (list of recorded performances): “The thematic cross-references to Beethoven come thick and fast . . . yet such is the Stenhammar ensemble’s passionate sense of identity with this music that they feel more like a series of inspired homages (as the composer intended) than mere plagiarism.”

- String Quartet No. 5 in C Major, Op. 29, “Serenade” (1910) (approx. 19-20’) (list of recorded performances): “Many have seen this work as Stenhammar’s tribute to Classical Viennese chamber music.”

- String Quartet No. 6 in D minor, Op. 35 (1916) (approx. 25’) (list of recorded performances): “An atmosphere of melancholy, sadness and even angst prevails. It is a deeply personal quartet. Maybe it was the composer’s tribute to Tor Aulin who died the year the quartet was started.”

Albums:

- Grant Green, “Alive!” (1970) (38’): We could say that being fully involved is being fully alive.

- Mike Gibbs Band, “Symphony Hall, Birmingham 1991” (114’): the sense of involvement is palpable.

- Trio Casals, “Moto Eterno” (2021): “With its inherent innovation, zest, vigor and verve, MOTO ETERNO proves to be another triumph for the long running series: a journey full of musical twists and turns, at times soothing, at times furious, and highly immersive throughout.”

- Moonlight Benjamin, “Wayo” (2023) (39’) “is a raw, explosive and uplifting album and a totally immersive listen. The epithet “Vodou Priestess of Blues-Rock' sits well on Moonlight Benjamin . . .”

- Justin Taylor, “Bach & L’Italie” (2023) (72’): “This thoughtfully planned programme exploring Bach’s affinities with his Italian contemporaries includes his famous Concerto ‘in the Italian style’ and several reworkings of concertos by the Venetian composers Vivaldi and Alessandro Marcello. . . French-American harpsichordist Justin Taylor brings youthful vitality and flair to these performances . . .”

Music: songs and other short pieces

- “Get on Board, Everybody!” (revision of “Get on Board, Little Children”) (lyrics)

- Jennifer Lopez, "Live It Up" (lyrics)

Visual Arts

- Marc Chagall, The Juggler (1943).

- Salvador Dali, Self-Portrait in the Studio (ca. 1919).

Film and Stage

- Genevieve, in which “two couples become increasingly--and hilariously--competitive as they near the finishing line” during an automobile race

- Household Saints, a working person’s version of life: put one foot in front of the other

A well-constructed mystery illustrates the idea of emotional involvement. The heart quickens, the skin crawls, sweat appears. If only every science student could muster that degree of emotional involvement for the subject matter!

Alfred Hitchcock was a master of the genre. “. . . very few lawyers are gifted with the special ability which is his to put a case together in the most innocent but subtle way, to plant prima facie evidence without arousing the slightest alarm and then suddenly to muster his assumptions and drive home a staggering attack.”

- The Lady Vanishes: “when your sides are not aching from laughter your brain is throbbing in its attempts to outguess the director”

- Suspicion, a few suggestions culminate in a devastation revelation

- Strangers On a Train, about the fear of being accused of a crime one did not commit

- Dial M for Murder

- Rear Window, “both mousetrap and abyss,” in which, along with the protagonist, we are “trapped inside his point of view, inside his lack of freedom and his limited options”; “a masterpiece of indirect exposition (that) lets the moviegoer play Peeping Tom until all at once he sees something that strikes him as — well, peculiar”; the “most bittersweet of Hitchcockian suspense-romances”

- North by Northwest

- The Birds, testing the limits of what people can be afraid of, and a great film maker’s ability to reach the seat of fear

Agatha Christie was a great mystery writer but Hitchcock did not direct films based on her stories. Creating suspense is an art, which can be expressed in writing or on film, but one medium does not necessarily translate directly to another. “Some people don’t know how to tell a joke.” As a result, there are fewer great Agatha Christie films than Hitchcock films:

Other excellent films in this genre include: