When we are not free, we may seek to liberate ourselves, so that we may choose our own course of action as autonomous beings.

- When none could eat any more, the Ivinses’ daughters asked William and Ellen if they could read. No, was the response, to which their hosts replied that if the Crafts wished to learn, they would be happy to teach them. Swiftly, the plates, and the remnants of the meal came off the table. Out came an assortment of books and slates. And thus it was that within days of her self-emancipation, Ellen began her lifelong dream of learning to write and read. [Ilyon Woo, Master Slave Husband Wife: An Epic Journey from Slavery to Freedom (2023), p. 136: having arrived safely in a free state, two people embark on their liberation.]

- As a black woman, my politics and political affiliation are bound up with and flow from participation in my people’s struggle for liberation, and with the fight of oppressed people all over the world against American imperialism. [attributed to Angela Davis]

- What a liberation to realize that the ‘voice in my head’ is not who I am. ‘Who am I, then?’ The one who sees that. [Eckhart Tolle]

- Revenge only engenders violence, not clarity and true peace. I think liberation must come from within. [attributed to Sandra Cisneros]

- Once I knew only darkness and stillness. Now I know hope and joy. Once I fretted and beat myself against the wall that shut me in. Now I rejoice in the consciousness that I can think, act and attain heaven. My life was without past or future; death, the pessimist would say, “a consummation devoutly to be wished.” But a little word from the fingers of another fell into my hand that clutched at emptiness, and my heart leaped to the rapture of living. Night fled before the day of thought, and love and joy and hope came up in a passion of obedience to knowledge. Can anyone who has escaped such captivity, who has felt the thrill and glory of freedom, be a pessimist? [Helen Keller, “Optimism” (1903), Part i.]

“When the soul or culture of some persons are oppressed, we are all oppressed and wounded in ways that require healing if we are to become liberated from such oppression.” Becoming liberated is the act of breaking free from constraint. Constraint may be physical, spiritual or both. Those who experience a moment of liberation usually remember it all their lives. Our art and literature celebrate that life-changing moment in the lives of many when the body and/or the spirit becomes free.

“Liberation psychology aims to analyze and transform personal and social oppression.” It is applicable at personal and social levels. Personal liberation may be from violent or toxic relationships. In its social and cultural dynamics, “. . . liberation psychology, which originated in Latin America and was founded by Martín-Baró, is centered on both structural and individual factors . . .”

Spiritual liberation is a form of solitary transcendence from previous limitations. “. . . solitary transcendence challenges traditional notions by emphasizing the individual’s capacity for spiritual growth and transformation without reliance on external sources. It highlights the significance of introspection, self-reliance, and personal spiritual experiences in the pursuit of liberation.” “Hui-neng developed the Buddhist thought of liberation and constructed the theory of spiritual liberation with Chinese characteristics Hui-neng s theory of spiritual liberation is a kind of life wisdom which aims to make people free from various afflictions and realize the freedom of the spirit.”

Real

True Narratives

Some of the best slaveholders will sometimes give their favourite slaves a few days' holiday at Christmas time; so, after no little amount of perseverance on my wife's part, she obtained a pass from her mistress, allowing her to be away for a few days. The cabinet-maker with whom I worked gave me a similar paper, but said that he needed my services very much, and wished me to return as soon as the time granted was up. I thanked him kindly; but somehow I have not been able to make it convenient to return yet; and, as the free air of good old England agrees so well with my wife and our dear little ones, as well as with myself, it is not at all likely we shall return at present to the "peculiar institution" of chains and stripes. [Running a Thousand Miles for Freedom; or, the Escape of William and Ellen Craft from Slavery (1860).]

Other narratives

- Rosa Cavalleri was an Italian who escaped from an abusive husband who had forced her into prostitution. Her life is chronicled in Marie Hall Ets, Rosa: The Life of an Italian Immigrant (University of Minnesota Press, 1970).

- Isaac Mizrahi, L.M.: A Memoir (Flatiron Books, 2019): “Isaac Mizrahi Found Freedom Through Fashion” and by being authentic.

- Amber Scorah, Leaving the Witness: Exiting a Religion and Finding a Life (Viking, 2019): “Many fundamentalists are conscious of the seeming absurdity of their position, but it is precisely the stridency of their faith, their ability to withstand the irrational, that confirms for them their exceptionalism and salvation.” “. . . it was through an email correspondence with a man that Scorah found the courage to court apostasy, focusing on the contradictions in Witness doctrine, its misogyny, and how its promotion of ignorance and lack of education undermines any sense of personal choice, rendering the word almost meaningless.”

- Joe Meno, Between Everything and Nothing: The Journey of Seidu Mohammed and Razak Iyal and the Quest for Asylum (Counterpoint, 2020): “Seidu’s identity as a queer man and Razak’s dispute with his half siblings over inherited land could well have made their situations intolerable. But what matters just as much is that the men were willing to abandon everything that was familiar to risk the unknown, that the promise of greater opportunity became just as urgent as what was pushing them to go.”

- Wayétu Moore, The Dragons, The Giant, The Women: A Memoir (Graywolf Press, 2020): “. . . framed by her family’s harrowing escape from (Liberia's) civil war, which broke out in 1989, spanned 14 years and resulted in the deaths of hundreds of thousands, with millions more displaced.”

- Paulina Bren, The Barbizon: The Hotel That Set Women Free (Simon & Schuster, 2021): “. . . Bren’s book is really about the changing cultural perceptions of women’s ambition throughout the last century, set against the backdrop of that most famous theater of aspiration, New York City.”

- Nana Darkoa Sekyiamah, The Sex Lives of African Women: Self-Discovery, Freedom, and Healing (Astra House, 2022), “explores women’s experiences, in their own words, helping foster 'a sexual revolution that’s happening across our continent.'”

- Ilyon Woo, Master Slave Husband Wife: An Epic Journey from Slavery to Freedom (Simon & Schuster, 2023), “relates the daring escape from bondage in Georgia to freedom in the North by an enslaved couple disguised as a wealthy planter and his property.”

- Rachel Louise Snyder, Women We Buried, Women We Burned: A Memoir (Bloomsbury Publishing, 2023): “Rachel Louise Snyder lost her mother to cancer at 8 and was kicked out of her high school and her home at 16. (This memoir) chronicles her quest to create a fulfilling life on her own terms.”

- Matthew Longo, The Picnic: A Dream of Freedom and the Collapse of the Iron Curtain (W.W. Norton & Company, 2023), “revisits in captivating detail the actions of ordinary people during that heady summer of 1989, when the Iron Curtain cracked and a magical word — ‘freedom’ — swept across the Eastern bloc. Within two years, the Soviet empire was over.”

On the dark side:

- Robert Service, A History of Modern Russia: From Nicholas II to Vladimir Putin (Harvard University Press, 2005).

Technical and Analytical Readings

Photographs

Documentary and Educational Films

Imaginary

Fictional Narratives

. . . while Rome is undergoing gradual dismemberment, Romanesque architecture dies. The hieroglyph deserts the cathedral, and betakes itself to blazoning the donjon keep, in order to lend prestige to feudalism. The cathedral itself, that edifice formerly so dogmatic, invaded henceforth by the _bourgeoisie_, by the community, by liberty, escapes the priest and falls into the power of the artist. The artist builds it after his own fashion. Farewell to mystery, myth, law. Fancy and caprice, welcome. Provided the priest has his basilica and his altar, he has nothing to say. The four walls belong to the artist. The architectural book belongs no longer to the priest, to religion, to Rome; it is the property of poetry, of imagination, of the people. Hence the rapid and innumerable transformations of that architecture which owns but three centuries, so striking after the stagnant immobility of the Romanesque architecture, which owns six or seven. Nevertheless, art marches on with giant strides. Popular genius amid originality accomplish the task which the bishops formerly fulfilled. Each race writes its line upon the book, as it passes; it erases the ancient Romanesque hieroglyphs on the frontispieces of cathedrals, and at the most one only sees dogma cropping out here and there, beneath the new symbol which it has deposited. The popular drapery hardly permits the religious skeleton to be suspected. One cannot even form an idea of the liberties which the architects then take, even toward the Church. There are capitals knitted of nuns and monks, shamelessly coupled, as on the hall of chimney pieces in the Palais de Justice, in Paris. There is Noah’s adventure carved to the last detail, as under the great portal of Bourges. There is a bacchanalian monk, with ass’s ears and glass in hand, laughing in the face of a whole community, as on the lavatory of the Abbey of Bocherville. There exists at that epoch, for thought written in stone, a privilege exactly comparable to our present liberty of the press. It is the liberty of architecture. This liberty goes very far. Sometimes a portal, a façade, an entire church, presents a symbolical sense absolutely foreign to worship, or even hostile to the Church. In the thirteenth century, Guillaume de Paris, and Nicholas Flamel, in the fifteenth, wrote such seditious pages. Saint-Jacques de la Boucherie was a whole church of the opposition. Thought was then free only in this manner; hence it never wrote itself out completely except on the books called edifices. Thought, under the form of edifice, could have beheld itself burned in the public square by the hands of the executioner, in its manuscript form, if it had been sufficiently imprudent to risk itself thus; thought, as the door of a church, would have been a spectator of the punishment of thought as a book. Having thus only this resource, masonry, in order to make its way to the light, flung itself upon it from all quarters. [Victor Hugo, Notre-Dame de Paris, or, The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1831), Volume I, Book Fifth, Chapter II, “This Will Kill That”.]

Novels:

- Esi Edugyan, Washington Black: A Novel (Alfred A. Knopf, 2018): A young man imagines and achieves a new life for himself. “His urge to live all he can is matched by his eloquence, his restless mind striving beyond its own confines in tones that are sometimes overstretched, if brilliant, and then filled with calm subtlety and nuance.”

- Otessa Moshfegh, My Year of Rest and Relaxation: A Novel (Penguin Press, 2018): “. . . Moshfegh’s darkly comic and ultimately profound new novel, also concerns itself with a miserable woman in her mid-20s seeking ‘great transformation.’ This unnamed narrator, however, takes a vastly different approach: She plans to spend a year sleeping.”

- E.J. Levy, The Cape Doctor: A Novel (Little, Brown and Company, 2021): “Learning new ways to walk, talk and think proves so liberating that abandoning the hoax, even when the opportunity arises, seems impossible.”

- Naomi Hirahara, Clark and Division: A Novel (Soho Press, 2021): “This is as much a crime novel as it is a family and societal tragedy, filtering one of the cruelest examples of American prejudice through the prism of one young woman determined to assert her independence, whatever the cost.”

- Lawrence Osborne, The Glass Kingdom: A Novel (Hogarth, 2020): “The main character of 'The Glass Kingdom' is the glass Kingdom, the apartment complex, with its yellow flowers in the lobby denoting the owner’s loyalty to the authorities, even as civil unrest leads to frequent power cuts and the rainy season gathers oppressive force. . . . the Kingdom becomes half refuge, half prison.” The protagonist struggles to liberate herself.

- Gabriel Cabezón Cámara, The Adventures of China Iron: A Novel (2017): “. . . a historical novel that reminds us, in Cabezón Cámara’s entrancing poetry, how magical and frankly unpleasant it is to live through history. The book is also a masterly subversion of Argentine national identity.”

- Daniel Kehlmann, Tyll; A Novel (Pantheon, 2020), “transmits the 14th-century tale of the jester Tyll Ulenspiegel about 300 years into the future, plopping him into the Thirty Years’ War. Tyll travels through a Europe devastated by conflict, encountering fraudsters, soldiers and royalty, including Queen Elizabeth of Bohemia, whose love of Shakespeare chimes with Tyll’s own sense of theatrical spectacle.” It is about being liberated through art.

- Gabriela Garcia, Of Women and Salt: A Novel (Flatiron, 2021): “Garcia’s women contend with abusive partners and abusive countries, and both leave them legacies they can’t evade.”

- Kaitlin Greenidge, Libertie: A Novel (Algonquin, 2021): “. . . Greenidge both mines history and transcends time, centering her post-Civil-War New York story around an enduring quest for freedom.”

- Elizabeth Weiss, The Sisters Sweet: A Novel (Dial Press, 2021): after freeing herself from a life as a conjoined twin forced to perform as a freak, “Harriet — now untethered — attempts to find an identity of her own. She builds this new self gradually, apart from her parents’ knowledge, by making friends and having experiences that could ruin them yet again if revealed.”

- Xochitl Gonzalez, Olga Dies Dreaming: A Novel (Flatiron Press, 2022): “The story’s driving tension derives from questions of how to break free: from a mother’s manipulations, from shame, from pride indistinguishable from fear, from the traumatic burden of abandonment, from colonial oppression, from corrosive greed.”

- Casey McQuiston, I Kissed Sarah Wheeler: A Novel (Wednesday Books, 2022): “. . . a queer teenage rebel is on the hunt to find her school’s missing golden girl, who, it turns out, is hiding a few secrets.”

- Jennifer Weiner, The Breakaway: A Novel (Atria Books, 2023): “. . . a woman at a crossroads agrees to lead a cycling trip that turns out to be more than she bargained for.”

- Nnedi Okorafor, Death of the Author: A Novel (William Morrow, 2025), “traces a Nigerian American woman’s quest for freedom and self-invention despite the social and cultural conventions that try to contain her.”

Poetry

One of my wishes is that those dark trees, / So old and firm they scarcely show the breeze, / Were not, as 'twere, the merest mask of gloom, / But stretched away unto the edge of doom.

I should not be withheld but that some day / Into their vastness I should steal away, / Fearless of ever finding open land, / Or highway where the slow wheel pours the sand.

I do not see why I should e'er turn back, / Or those should not set forth upon my track / To overtake me, who should miss me here / And long to know if still I held them dear.

They would not find me changed from him they knew-- / Only more sure of all I though was true.

[Robert Frost, “Into My Own” (analysis)]

Other poems:

- Frances Ellen Watkins Harper, “Learning to Read”

Music: Composers, artists, and major works

Compositions:

- George Frideric Händel’s oratorio Israel in Egypt, HWV 54 (1738) (approx. 80-110’) (libretto) (list of recorded performances) tells the biblical story of a people’s liberation from its oppressors. “With its use of scripture as libretto, increased use of chorus and double chorus, and diminished role of soloists, Israel in Egypt stands alone in scope and style among all of Handel’s oratorios.” Performances are conducted by Christie, Gardiner with English Baroque Soloists, Gardiner with Monteverdi Choir & Orchestra, Christophers, Bramall, Hengelbrock, Luks, and Cleobury.

- Gustave Charpentier, Louise (1900) (approx. 163-177’) (libretto) (list of recorded performances) is described as a musical novel. The story is of a remarkable fuss over a young woman leaving her parents’ home to embark on a new life with a man. Performances are conducted by Fournet, Armin, Cambreling and Rudel.

- Ferdinando Carulli, Guitar Sonatas, Opp. 5 & 21 (ca. 1810, 1811)

- Enrique Granados, 12 Danzas Españolas (12 Spanish Dances), Op. 37, DLRI:2, H142 (1890) (approx. 53-61’) (list of recorded performances)

- Gordon Green’s arrangements and variations for digital piano free the performance from the earthly constraints of hands and fingers.

- Kalevi Aho, Symphony No. 4 (1973) (approx 45’): tragedy gives way to liberation.

- Mily Balakirev, Piano Concerto No. 1 in F-sharp Minor, Op. 1 (1856) (approx. 13-14’) (list of recorded performances)

- Stefan Wolpe, Sonata for Violin & Piano (1949) (approx. 27-30’): Wolpe described this work as “one of the first pieces which show my personal liberation, or my personal restoration”.

- Pedro António Avondado, Il mondo della luna (The World of the Moon) (1750) (approx. 135-140’), is an opera buffa in which two young women escape from their father’s heavy hand to (guess what!) marry their lovers.

- Baldasare Galuppi, Il mondo della luna (The World of the Moon) (1750) (approx. 166’)

- Franz Joseph Haydn, Il mondo della luna (The World of the Moon) (Die Welt auf dem Monde), Hob. XXVIII:7 (1777) (approx. 145-170’) (list of recorded performances): Haydn was not to be outdone by Avondado, Galuppi and several other composers who set Carlo Goldoni’s tale to music.

- Ondřej Adámek, Concerto for Violin and Orchestra, “Follow Me” (2017) (approx. 26’): “In Adámek’s 'Follow me', a three-movement concerto for violin and orchestra, the melodies are divided between the soloist and the orchestra along the lines of the late medieval hocket technique, whereby the composer seeks to connect a single individual with a (human) crowd.” “The work musically depicts dynamics between a leader and his/her followers, where the relationship between leader and followers begins in a somewhat orderly fashion but soon devolves into parody and finally chaos and rebellion.”

- Tõnu Kõrvits, The Sound of Wings (Tiibade hääl) (2022) (approx. 50’) “sets texts by Estonian poet Doris Kareva that were inspired by Amelia Earhart’s ill-fated 1937 attempt to fly around the world. The poems deal more with the philosophical aspects of flight—of air, wind, water, stars—than with actual events . . .” “Kõrvits uses the solo viola as his focus instrument, creating the sound of the wind also in his writings for the chorus and orchestra. The introduction brings both sound and silence, summoning up both the wind and the air, flight, and the feeling of freedom. For Earhart, flight was freedom and liberation from both the ground and the things that kept women back in the early 20th century.”

- Barbara Harbach, Symphony No. 13, “The Journey” (approx. 25’) “tells the life story of fugitive slaves (William and Ellen Craft) as abolitionists.”

- Gabriela Ortiz, Yanga (2019) (approx. 18’) “originated when Alejandro Escuer, a Mexican flutist who has recorded an album of music by Ortiz, presented her with the idea of an opera about Gaspar Yanga. Yanga was the African-born leader of a band of formerly enslaved people who successfully resisted recapture by the Spanish in the early 17th century.” “. . . Yanga is a work about an immense expressive force that speaks of the greatness of humanity when in search of equality and the universal right to enjoy freedom to the fullest.”

Albums:

- Gustavo Cortiñas, “Desafio Candente” (2021) (96’), was inspired by Eduardo Galeano’s book The Open Veins of Latin America – it is about their struggle for liberation.

- Lido Pimienta, “Miss Colombia” (2020) (44’), is a “series of cynical love letters to (Pimienta’s) native Columbia”, and a declaration of the singer’s independence.

- Binker Golding, “Dream Like a Dogwood Wild Boy” (2022) (54’): from the Texas prairie to a jazz club in the city

- The Ethiopian, “Open the Gates of Zion” (1978) (34’), is a Reggae classic about liberation in youth.

- Various artists, “The Trojan Story” (132’): pre-Reggae music from Jamaica

- Desdemona, “Tús” (2022) (63’) (music of Finola Merivale): “Pent-up feelings demand release. Freedom is achieved when everything that suffocates and confines is smashed to pieces.” “. . . the album includes five works for various instrumental configurations within the quintet that demonstrate Merivale’s penchant for creating evocative textures that emerge from her adept handling of instrumental subtleties.”

- Jon Batiste, “Beethoven Blues” (2024) (51’) presents Beethoven’s music, infused with jazz and other liberating influences. “Beethoven Blues is a solo piano album. It consists of a sequence of some of Beethoven’s most popular pieces, as ‘reimagined’ by Batiste.”

- Molly Tuttle, “So Long Little Miss Sunshine” (2025) (46’): musically and in content, the album is about taking to the open road.

Music: songs and other short pieces

- Jennifer Higdon, “Amazing Grace” (2003): composed for string quartet, this version of the famous hymn sounds like personal liberation.

- Giorgio Moroder & Philip Oakley, “Together in Electric Dreams”: I know a man who danced to this music, and liberated himself.

- Franz Schubert (composer), “Drang in die Ferne” (Longing to Escape), D. 770 (1823) (lyrics)

- The Rolling Stones, “Wild Horses” (lyrics)

Visual Arts

There is political liberation:

- René Magritte, On the Threshold of Liberty (1930)

- Eugene Delacroix, Liberty Leading the People (1830)

There is liberation of one person by another:

- Peter Paul Rubens, Perseus Liberating Andromeda (1622)

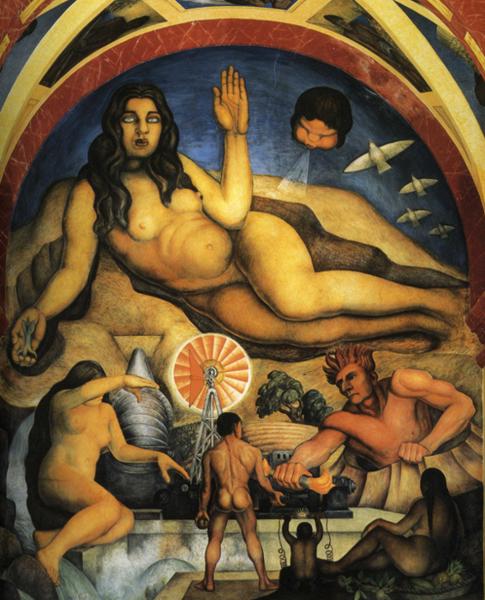

There is liberation of the self, as in Diego Rivera's painting at the top of this page.

Film and Stage

- Precious: an obese teenage girl, living with her dis-spirited and abusive mother, crawls her way to normalcy

- The Piano, the story of a gifted pianist's struggle to find her identity

- Paisà (Paisan), an Italian neorealist film of “six episodes, each elucidating upon the tenuous relationship between the recently liberated Italians and their American liberators”

- Thelma and Louise, Thelma and Louise, a tragic-comic look at personal liberation

- Zero for Conduct (Zero de Conduite): rebellion in a boarding school

- Real Women Have Curves: a young Hispanic woman navigates her way – sometimes lovingly, sometimes in exasperation – through a family experience that would hold her back, if she allowed that.