Perhaps the main factor that creates meaning is a sense of connection – an essential part of spirituality.

- A soul that is kind and intends justice discovers more than any sophist. [Widely attributed to Sophocles]

- The biggest adventure you can take is to live the life of your dreams. [Oprah Winfrey]

- And what about all of the scholars and critics over the years who despaired that Leonardo squandered too much time immersed in studying optics and anatomy and the patterns of the cosmos? The Mosa Lisa answers them with a smile. [Walter Isaacson, Leonardo da Vinci, p. 494.]

Meaning is essential to flourishing, perhaps to living. A person who feels that life is meaningless is at risk for depression and is likely to have difficulty functioning: after all, if nothing matters, then there is no reason to do anything. Absence of meaning can lead to suicide.

Meaning is a function of how we look at things. We can decide what our lives mean to us, to a point. People who find a sense of meaning in their lives are more likely to be happy and to contribute to the well-being of others, because a sense of meaning cements the relationship to human preferences, bringing them to life and making them tangible.

Meaning is largely about connection. “A sense of meaning and purpose can be derived from belonging to and serving something bigger than the self.” “Employees can find meaning if they can connect their work—and the work of their organizations—with value. In some cases, such as with a charity, nonprofit, or health services provider, that connection may be easy to make. . . . Some people find meaning by engaging with the arts or expressing their creativity. This could involve listening to a moving vocal performance, viewing a beautiful painting, or crafting a short story.”

Real

True Narratives

Humans employ complex symbolic languages to communicate. This makes possible a rich life of meaning. The history of language translation offers a particular insight into the attainment of meaning through symbols, which is an essential first step toward what most people call “deeper meaning”.

- David Bellos, Is That a Fish in Your Ear?: Translation and the Meaning of Everything (Faber & Faber, 2011). A good translation is "more like a 'portrait in oils'" than a school quiz.

- C.G. Jung, The Red Book: Liber Novus (1930): the great psychiatrist’s attempt to represent the mind symbolically.

Other narratives on meaning as an aspect of flourishing:

- Lucy Grealy, Autobiography of a Face (Houghton Mifflin, 1994): “‘Autobiography of a Face’ is a book about many things: sickness and health, body and soul, gender and social expectation. It is, importantly, a book about image, about the tyranny of the image of a beautiful -- or even a pleasingly average -- face. In the end, this tyranny is not so much overthrown as shrugged off.”

Technical and Analytical Readings

- Sheila A.M. Rauch & Barbara Olasov Rothbaum, Making Meaning of Difficult Experiences: A Self-Guided Program (Oxford University Press, 2023).

- Iddo Landau, Finding Meaning in an Imperfect World (Oxford University Press, 2017).

- Alisse Waterston, Light in Dark Times: The Human Search for Meaning (University of Toronto Press, 2020).

- Christopher Bollas, Meaning and Melancholia: Life in the Age of Bewilderment (Routledge, 2018).

- Clay Routledge, Past Forward: How Nostalgia Can Help You Live a More Meaningful Life (Sounds True, 2023).

- Pninit Russo-Netzer, Stefan E. Schulenberg & Alexander Batthyany, eds., Clinical Perspectives on Meaning: Positive and Existential Psychotherapy (Springer, 2016).

Photographs

Documentary and Educational Films

Imaginary

Fictional Narratives

In O. Henry’s iconic short story, two young lovers sacrifice their most prized possessions, and are rewarded with something far more important, and meaningful.

“Jim, darling,” she cried, “don’t look at me that way. I had my hair cut off and sold because I couldn’t have lived through Christmas without giving you a present. It’ll grow out again—you won’t mind, will you? I just had to do it. My hair grows awfully fast. Say ‘Merry Christmas!’ Jim, and let’s be happy. You don’t know what a nice—what a beautiful, nice gift I’ve got for you.” / “You’ve cut off your hair?” asked Jim, laboriously, as if he had not arrived at that patent fact yet even after the hardest mental labor. / “Cut it off and sold it,” said Della. “Don’t you like me just as well, anyhow? I’m me without my hair, ain’t I?” / Jim looked about the room curiously. / “You say your hair is gone?” he said, with an air almost of idiocy. / “You needn’t look for it,” said Della. “It’s sold, I tell you—sold and gone, too. It’s Christmas Eve, boy. Be good to me, for it went for you. Maybe the hairs of my head were numbered,” she went on with sudden serious sweetness, “but nobody could ever count my love for you. Shall I put the chops on, Jim?” / Out of his trance Jim seemed quickly to wake. He enfolded his Della. For ten seconds let us regard with discreet scrutiny some inconsequential object in the other direction. Eight dollars a week or a million a year—what is the difference? A mathematician or a wit would give you the wrong answer. The magi brought valuable gifts, but that was not among them. This dark assertion will be illuminated later on. / Jim drew a package from his overcoat pocket and threw it upon the table. / “Don’t make any mistake, Dell,” he said, “about me. I don’t think there’s anything in the way of a haircut or a shave or a shampoo that could make me like my girl any less. But if you’ll unwrap that package you may see why you had me going a while at first.” / White fingers and nimble tore at the string and paper. And then an ecstatic scream of joy; and then, alas! a quick feminine change to hysterical tears and wails, necessitating the immediate employment of all the comforting powers of the lord of the flat. / For there lay The Combs—the set of combs, side and back, that Della had worshipped long in a Broadway window. Beautiful combs, pure tortoise shell, with jewelled rims—just the shade to wear in the beautiful vanished hair. They were expensive combs, she knew, and her heart had simply craved and yearned over them without the least hope of possession. And now, they were hers, but the tresses that should have adorned the coveted adornments were gone. / But she hugged them to her bosom, and at length she was able to look up with dim eyes and a smile and say: “My hair grows so fast, Jim!”

And then Della leaped up like a little singed cat and cried, “Oh, oh!” / Jim had not yet seen his beautiful present. She held it out to him eagerly upon her open palm. The dull precious metal seemed to flash with a reflection of her bright and ardent spirit. / “Isn’t it a dandy, Jim? I hunted all over town to find it. You’ll have to look at the time a hundred times a day now. Give me your watch. I want to see how it looks on it.” / Instead of obeying, Jim tumbled down on the couch and put his hands under the back of his head and smiled. / “Dell,” said he, “let’s put our Christmas presents away and keep ’em a while. They’re too nice to use just at present. I sold the watch to get the money to buy your combs. And now suppose you put the chops on.” / The magi, as you know, were wise men—wonderfully wise men—who brought gifts to the Babe in the manger. They invented the art of giving Christmas presents. Being wise, their gifts were no doubt wise ones, possibly bearing the privilege of exchange in case of duplication. And here I have lamely related to you the uneventful chronicle of two foolish children in a flat who most unwisely sacrificed for each other the greatest treasures of their house. But in a last word to the wise of these days let it be said that of all who give gifts these two were the wisest. Of all who give and receive gifts, such as they are wisest. Everywhere they are wisest. They are the magi. [O. Henry, “The Gift of the Magi” (1905).]

In the gray zone:

At that time there lived in Rome a celebrated sculptor by the name of Aurelius. Out of clay, marble and bronze he created forms of gods and men of such beauty that this beauty was proclaimed immortal. But he himself was not satisfied, and said there was a supreme beauty that he had never succeeded in expressing in marble or bronze. “I have not yet gathered the radiance of the moon,” he said; “I have not yet caught the glare of the sun. There is no soul in my marble, there is no life in my beautiful bronze.” And when by moonlight he would slowly wander along the roads, crossing the black shadows of the cypress-trees, his white tunic flashing in the moonlight, those he met used to laugh good-naturedly and say: “Is it moonlight that you are gathering, Aurelius? Why did you not bring some baskets along?” And he, too, would laugh and point to his eyes and say: “Here are the baskets in which I gather the light of the moon and the radiance of the sun.” And that was the truth. In his eyes shone moon and sun. But he could not transmit the radiance to marble. Therein lay the greatest tragedy of his life. He was a descendant of an ancient race of patricians, had a good wife and children, and except in this one respect, lacked nothing. [Leonid Andreyev, “Lazarus” (1906).]

From the dark side:

In this scene from Dickens’ A Christmas Carol, the love of Scrooge’s life rejects him because love and money do not mean the same things to her as they do to him:

For again Scrooge saw himself. He was older now; a man in the prime of life. His face had not the harsh and rigid lines of later years; but it had begun to wear the signs of care and avarice. There was an eager, greedy, restless motion in the eye, which showed the passion that had taken root, and where the shadow of the growing tree would fall. He was not alone, but sat by the side of a fair young girl in a mourning-dress: in whose eyes there were tears, which sparkled in the light that shone out of the Ghost of Christmas Past. "It matters little," she said, softly. "To you, very little. Another idol has displaced me; and if it can cheer and comfort you in time to come, as I would have tried to do, I have no just cause to grieve." "What Idol has displaced you?" he rejoined. "A golden one." "This is the even-handed dealing of the world!" he said. "There is nothing on which it is so hard as poverty; and there is nothing it professes to condemn with such severity as the pursuit of wealth!" "You fear the world too much," she answered, gently. "All your other hopes have merged into the hope of being beyond the chance of its sordid reproach. I have seen your nobler aspirations fall off one by one, until the master-passion, Gain, engrosses you. Have I not?" "What then?" he retorted. "Even if I have grown so much wiser, what then? I am not changed towards you." She shook her head. "Am I?" "Our contract is an old one. It was made when we were both poor and content to be so, until, in good season, we could improve our worldly fortune by our patient industry. You are changed. When it was made, you were another man." "I was a boy," he said impatiently. "Your own feeling tells you that you were not what you are," she returned. "I am. That which promised happiness when we were one in heart, is fraught with misery now that we are two. How often and how keenly I have thought of this, I will not say. It is enough that I have thought of it, and can release you." "Have I ever sought release?" "In words. No. Never." "In what, then?" "In a changed nature; in an altered spirit; in another atmosphere of life; another Hope as its great end. In everything that made my love of any worth or value in your sight. If this had never been between us," said the girl, looking mildly, but with steadiness, upon him; "tell me, would you seek me out and try to win me now? Ah, no!" He seemed to yield to the justice of this supposition, in spite of himself. But he said with a struggle, "You think not." "I would gladly think otherwise if I could," she answered, "Heaven knows! When I have learned a Truth like this, I know how strong and irresistible it must be. But if you were free to-day, to-morrow, yesterday, can even I believe that you would choose a dowerless girl--you who, in your very confidence with her, weigh everything by Gain: or, choosing her, if for a moment you were false enough to your one guiding principle to do so, do I not know that your repentance and regret would surely follow? I do; and I release you. With a full heart, for the love of him you once were." He was about to speak; but with her head turned from him, she resumed. "You may--the memory of what is past half makes me hope you will--have pain in this. A very, very brief time, and you will dismiss the recollection of it, gladly, as an unprofitable dream, from which it happened well that you awoke. May you be happy in the life you have chosen!" She left him, and they parted. [Charles Dickens, A Christmas Carol (1843), Stave II: “The First of the Three Spirits”.]

Novels:

- Anna Quindlen, Miller’s Valley: A Novel (Random House, 2016): “What does home really mean? Is it the people around you who make a place familiar and loved, or is it the tie to land that’s been in your family for generations? Anna Quindlen’s mesmerizing new novel investigates both . . . ”

- Ann Napalitano, Dear Edward: A Novel (Dial, 2020): “While none of the adults in either the real crash or the novel it inspired survive, Napolitano’s fearless examination of what took place models a way forward for all of us. She takes care not to sensationalize, presenting even the most harrowing scenes in graceful, understated prose, and gives us a powerful book about living a meaningful life during the most difficult of times.”

- Daphne Palasi Andreades, Brown Girls: A Novel (Random House, 2022): “What matters in this novel isn’t that they die, but how much life the author pumps into them while they’re here.”

Poetry

Just as my fingers on these keys / Make music, so the selfsame sounds / On my spirit make a music, too.

Music is feeling, then, not sound; / And thus it is that what I feel, / Here in this room, desiring you,

Thinking of your blue-shadowed silk, / Is music. It is like the strain / Waked in the elders by Susanna:

Of a green evening, clear and warm, / She bathed in her still garden, while / The red-eyed elders, watching, felt

The basses of their beings throb / In witching chords, and their thin blood / Pulse pizzicati of Hosanna.

[Wallace Stevens, “Peter Quince at the Clavier”]

Other poems:

- Sara Teasdale, “The Dreams of My Heart”

From the dark side:

- Edgar Lee Masters, “Henry Phipps”

- Edgar Lee Masters, “Hortense Robbins”

Music: Composers, artists, and major works

Johannes Brahms’ Symphony No. 2 in D Major, Op. 73 (1877) (approx. 38-48’) (list of recorded performances), can easily be heard as an essential romantic symphony, and an idyll, but a closer listen reveals the life-affirming, generous components of kindness and meaning. It “is one of the most cheerful of his mature works, and its happy nature could be because it was composed during a summer holiday in 1877 while living on the shores of an Austrian lake.” Brahms’ friend Ferdinand Pohl said of it: “It’s a magnificent work that Brahms is bestowing on the world, and so very accessible as well. Every movement is gold, and all four together constitute a necessary whole. Vitality and strength are bubbling up everywhere, deep feeling and charm to go with it. Such music can only be composed in the country, in the midst of nature.” Top performances were conducted by Furtwängler in 1945, Toscanini in 1952, Klemperer in 1956, Szell in 1967, K. Sanderling in 1972, Bernstein in 1981, Abbado in 1989, Masur in 1989, Harnoncourt in 1997, Iván Fischer in 2014, and Blomstedt in 2015.

- The first movement (Allegro non troppo) begins with a pastoral and idyllic theme, soon followed, after a brief enthusiastic segue (1:42), by Brahms’ famous lullaby (2:21). Whatever Brahms may have intended, both motifs express an attitude of kindness. Affirmations of the themes appear repeatedly, for example, at 2:56. Dramatic variations (3:18) are not moments of doubt but occasions to return to the main theme (3:56, 4:26). The solo horn offers an affirmation (5:17), picked up and further affirmed by the orchestra and its several parts. Written in D major, the most resolved of all keys, this symphony promises to be a straight-ahead affirmation (for example, at 7:39). Like a baby in its mother’s arms, we are repeatedly and gently reminded of the essential theme (8:26) until the movement draws to its peaceful conclusion (12:40).

- The second movement (Adagio non troppo) sounds a commitment to goodness (1:07). The commitment, fully at one with its subject, deepens (2:19) and persists throughout the movement. The values of kindliness and service toward a deeply appreciated subject never waver. Occasionally the music seems to cry out for “more!” (7:09)

- The third movement (Allegretto grazioso [quasi Andantino] – Presto ma non assai) begins in an uncharacteristically similar vein for a third movement: peaceful, almost idyllic. At 1:12, Brahms begins to introduce a fuller affirmation. Members and sections of the orchestra affirm each other repeatedly (for example, at 2:20). The main theme is infused with new energy (2:57).

- The fourth movement (Allegro con spirito) begins quietly but quickly opens into boisterous enthusiasm (0:30). A new warmth appears (1:33), affirming and augmenting the old themes. This work is a generous affirmation, at one with its subject, in other words, a work of great generosity ending, as we might expect with a vigorous affirmation of the pervasive theme (6:00 to end).

Artur Schnabel was widely considered to be the greatest classical pianist of his time. “. . . Schnabel grasped the music from the inside out.” “Much has been made of Leschetizky’s evaluation of his young pupil, 'You will never be a pianist; you are a musician' . . .” Perhaps this is because, despite many false steps technically, his pianism brings to mind a wide range of values, including “an amalgam of Viennese lyricism and German rigor”, expressive depth, intense concentration, wide emotional range, adherence to the composer’s intentions (“to the spirit rather than to the letter”), meticulous detail, and intellectual seriousness as a musician. Such a wide range of values is present in a meaningful life. Schnabel was always looking deeply into the music, often expressing an interest in music that was “better than it can be played”. Here is a link to his playlists.

Marianne Faithfull was a British popular singer whose career and musical output suggest a heartfelt search for meaning. “. . . she use(d) vocal sounds that evoke a hard-lived life—hoarseness, breathiness, a range markedly lower than her youthful voice, to claim authority over her own narrative. In her work on the so-called damaged voice, musicologist Laurie Stras writes that we hear disrupted or damaged voices as ‘a measure of the body’s cumulative experience’ that communicate more than the words they speak.” “After splitting up with Mick Jagger, Faithfull spent years living as a heroin addict on the streets of Soho. Given the chance to restart her singing career, she went on to make more than 20 albums. Her whisky-soaked voice, turned cracked and dusky, conveyed the inner torments of her painful life-experiences.” “. . . she was . . . an artist who embodied both the bright and the dark side of the 1960s dream.” “Cast Your Fate to the Wind: The Singles, B-Sides & Rarities” (82’) is a retrospective summary of her recordings.

A specific performance of Chopin, Piano Trio in G minor, Op. 8, by Trio D’Arte Vienna in February 2011 (30’)

These works by Édouard Lalo:

- Symphonie Espagnole in D Minor, Op. 21 (1874) (approx. 33-35’) (list of recorded performances)

- Violin Concerto No. 1 in F major, Op. 20 (1873) (approx. 25’) (list of recorded performances)

- Violin Concerto No. 2 in G Minor, "Concerto russe”, Op.29 (1879) (approx. 31’) (list of recorded performances)

Other works:

- Chrisstopher Tyler Nickel, Symphony No. 2 (2016, rev. 2018) (53’): this is music about the seriousness and importance of our lives, and about life's vagaries.

- Ralph Vaughan Williams, Fantasia on a Theme by Thomas Tallis (1910) (approx. 15-18’) (list of recorded performances), is a gorgeous, succinct masterwork, dripping with emotion and meaning, evocative of the inner life. Top recorded performances are conducted by Neel in 1936, Boult in 1976, Andrew Davis in 1991, Wordsworth in 1994, Elder in 2014, and Wilson in 2022.

- Ernest Chausson, Poème for Violin and Orchestra, Op. 25 (1896) (approx. 16-18’) (list of recorded performances): “The original story line, with the original title, is worthwhile examining as it gives us a clue that this work isn’t simply absolute music, but is telling a definite story. The plot concerns the unlucky passion…of a young musician for Valeria, who has preferred Fabius to him. . . The role of violin, representing the unrequited lover-musician, gives the opportunity for a truly emotional performance from the violinist . . .”

- Vittorio Giannini, Symphony No. 4 (1959) (approx. 23’)

- George Enescu, Poème roumaine, symphonic suite for orchestra and wordless male choir, Op. 1 (1897) (27-30’): the composer was invoking the “distant images of familiar images from home.”

- Healey Willan, Poem for Strings (1959) (approx. 7’)

- Christian Sinding, Violin Concerto No. 1 in A Major, Op. 45 (1898) (approx. 21-22’): “Written within the German late Romantic tradition, the Concerto exudes cheerful ebullience and lyrical charm . . .”

Samara Joy (McLendon) is a jazz singer whose interpretations convey genuine feeling, cutting to the core of life. Her vocal tone is reminiscent of Ella Fitzgerald but everything about her is uniquely Samara. Her albums include:

- “Linger Awhile” (2022): “Simply put, Samara Joy is next. Her Verve debut shows that, at just 22 years old, with a voice, tone, and phrasing that harkens back to the most iconic jazz vocalists of all time,”

- “Samara Joy” (2021): “Samara Joy is a singing star in ascendancy. The young vocalist attracted attention in 2019 after winning the Sarah Vaughan International Jazz Vocal Competition. Now, the 21-year-old announces her self-titled debut release, which puts her spin on jazz standards from the Great American Songbook. . . . Joy’s interpretations balance the breezy-fresh feel of a relative newcomer with a reverence for a tradition she is now undoubtably part of.”

Johanna-Adele Jüssi “is an Estonian fiddler living far North in Norway. . . . Her expression is both elegant and raw, it tells a story and weaves a spell. Whether she plays for dancing or listening, Johanna-Adele is always in the present, creating the moment, filling it with meaning.” Here is a link to her releases.

Albums:

- Bill Frisell, “East/West” (2005) (115’) “serves as confident assurance to his existing fans that his career has been driven by choice and the love of a good song.”

- Virko Baley & California E.A.R. Unit, “Dreamtime” (1994): “The charm of Mr. Baley's work, which is scored for violin, clarinet and piano, is in its use of comparatively simple, straightforwardly tonal and chromatic materials, and its lively use of parody and allusion.”

- Angelica Sanchez & Marilyn Crispell, “How to Turn the Moon” (2020) (50’): “. . . pianists Angelica Sanchez and Marilyn Crispell, have decided that it is their turn to sit down in tandem, on How to Turn the Moon, for the stirring up of the possibilities of so many potential chords, so many potential melodies, intertwined, complementary, often in a minimalist fashion, with the occasional storm of transitory maximalism rollicking into soundscapes.”

- Benjamin Boone, “The Poets Are Gathering” (2020) (72’): Boone “recruits a superb arsenal of poets who unravel their works with razor-sharp conviction and clarity. The marriage of jazz and poetry can invite as much scorn as it does celebration, perhaps stemming from spoken-word recitations overpowering middling music or accompaniment overcompensating for lackluster verses. But when deployed by Boone, the bond can be wondrous.”

- Charles Rumback, “June Holiday” (2020) (45’): “Overtones hang in the air only to be juddered by spasmodic clusters of cymbals and toms, summoning something far more meaningful than an unabashed love song or a freak out.”

- Las Lloronas, “Soaked” (2020) (47’): “Instrumentally, the use of accordion, guitar and clarinet allows them to flow around Europe, sucking the influences of Moorish Spain and North Africa, the Middle East, Eastern Europe, reinforcing the point that origins do not matter, what you care about matters.”

- Nitin Sawhney, “Last Days of Meaning” (2011) ) (52’): “. . . a fabulous nineteen-track album that takes the listener on an eclectic journey both around the world and in and out of people’s lives. . . . The album is interspersed with the various ‘reflections’ of an embittered old man . . .”

- Hannah Read & Michael Starkey, “Cross the Rolling Water” (2022) (43’): intermittently uplifting and poignant, bluegrass on fiddle and banjo. “Plain fiddle and banjo, unadorned, makes up the most of the album, proving anything other than one-dimensional. Apple Blossom opens and is a delight, a special, if you will, the two instruments all you need, together adding all the notes you need, none to waste and none to spare.”

- Kathryn Tickell & The Darkening, “Cloud Horizons” (2023) (44’): “Aptly described as ‘Ancient Northumbrian Futurism’, Kathryn Tickell and The Darkening’s Cloud Horizons is electrifying and incredibly captivating.”

- Julian Lage, “Speak To Me” (2024) (60’): “. . . Julian Lage is devoted to telling us stories through his music; it’s a music of tales, dialogue, perhaps even of novels.”

- Msaki x Tubatsi, “Synthetic Hearts” (2023) (34’) and “Synthetic Hearts Part II” (2024) (30’): “A gorgeously tender, stripped-back collaborative LP as South African singing star Msaki joins Soweto multi-instrumentalist and Keleketla! member Tubatsi Mpho Moloi, with accompaniment by Parisian cellist Clément Petit . . .” “Space is deeply considered throughout. Each instrument is highlighted and given emphasis through minimalistic arrangements while the vocals of Msaki and Tubatsi – harmonising, rhythmic and chanting in turn – are given space to breathe and flourish. The interplay between distance, connection and isolation carry through in both lyricism and arrangement.”

- The Crooked Fiddle Band, “The Free Wild Wind and the Song of Birds” (2024) (40’): “. . . an expansive and cinematic release which weaves together folk music traditions, post and progressive rock, and chamber music. The Free Wild Wind has a more reflective air than its predecessors, with a renewed focus on cinematic composition and dynamics.”

- Brad Mehldau, “Ride into the Sun” (2025) (73’): “‘“Ride into the sun”’ is a beautiful point in the lyric of one of the songs that we play, “Colorbars,”’ Mehldau says. ‘Elliott Smith says in the original song, “Everyone wants me to ride into the sun.” When I listen to music, I have a feeling that I can be in communion with somebody who is no longer in this earthly realm, like he is here. And as far as “riding into the sun,” it’s maybe more of a perpetual riding into the sun with him. I don’t know ... There’s something mystical there.’”

On the dark side:

- Alberto Ginastera, Bomarzo (1967) (approx. 131-136’): in this opera, a man looks back on his life after being poisoned. Performances are conducted by Tauriello and Rudel.

Music: songs and other short pieces

- Fred Stobaugh, “Oh Sweet Lorraine”

- Franz Schubert (composer), Der Alpenjäger (The Alpine Huntsman), D. 524 (1817) (lyrics)

- Franz Joseph Haydn (composer), “The Spirit’s Song”, Hob. XXVIa:41 (lyrics)

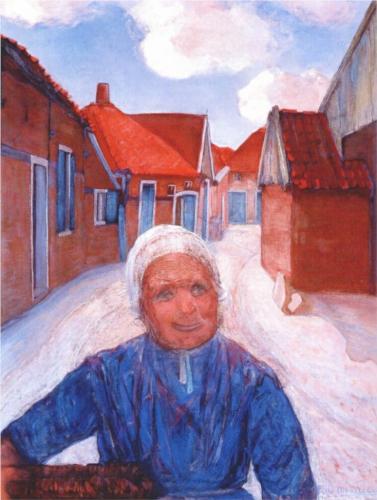

Visual Arts

- Giorgio de Chirico, The Uncertainty of the Poet (1913)

Film and Stage

- Il Postino (The Postman), a film exploring the rich emotional life of the poet Pablo Neruda

- Ninotchka: this spoof on Soviet materialism may not reflect a high level of spiritual development but it makes the important point that no one can live without a sense of meaning

- Silk Stockings is an updated musical version of Ninotchka

- That’s Life!: a film that explores what matters most

- The Thin Red Line, a war film that “contemplates mankind's self-destructiveness, the oneness of a company of soldiers, the rape of nature and the emptiness of Pyrrhic victory on the battlefield”

- Paterson, about two people finding meaning in their own quirky ways, and in each other