Reverence – natural piety – is a useful attitude that lifts us to higher ground, inspires us, and makes us more productive.

- . . . I might pursue some path, however narrow and crooked, in which I could walk with love and reverence. [Henry David Thoreau]

- . . . reverence for life contains all the components of ethics: love, kindliness, sympathy, empathy, peacefulness, power to forgive. [Albert Schweitzer]

- Through reverence for life, we enter into a spiritual relation with the world. [Albert Schweitzer]

- In the presence of nature, a wild delight runs through the man. in spite of real sorrows. Nature says, “He is my creature, and . . . that is enough.” [Ralph Waldo Emerson, Nature (1849).]

- We are part of the earth and it is part of us. The perfumed flowers are our sisters; the deer, the horse, the great eagle, these are our brothers. [Chief Seattle]

- The most common trait of all primitive peoples is a reverence for the life-giving earth, and the Native American shared this elemental ethic: The land was alive to his loving touch, and he, its son, was brother to all creatures. [Stewart Udall, apparently]

Reverence is an attitude, and a way of looking at things. Many religious naturalists describe this as natural piety. “Both Emerson and Dewey described forms of naturalism wherein humanity might pursue the ideal ends of their lives in a structured, valuable pattern of activity as they interact with nature. It was Dewey who made use of the term ‘natural piety’, but both urged mankind to practice a form of natural piety.”

In this model, reverence implies deep respect for nature, including the physical world, the laws of nature, and living beings. It is accompanied by a sense of awe and wonder.

Religious naturalism implies that the sacred is found in nature. (Where else would you expect to find it?) “. . . nature often induces awe, wonder, and reverence, all emotions known to have a variety of benefits, promoting everything from well-being and altruism to humility to health.” It embraces reality, and finds inspiration in it.

“. . . reverence is a cardinal virtue that embraces meaning and purpose in life. It is also a self-transcending positive emotion, associated with specific worldviews that may determine the context in which an individual senses it.” Goodenough, et. ano. maintain: “. . . the four cardinal virtues—courage, fairmindedness, humaneness, and reverence—are rendered coherent by mindful reflection. We focus on the concept of mindful reverence and propose that the mindful reverence elicited by the evolutionary narrative is at the heart of religious naturalism. Religious education, we suggest, entails the cultivation of mindful virtue, in ourselves and in our children.”

Real

True Narratives

Many people's lives and work could be cited to illustrate natural piety, or religious naturalism. Among them is Ralph Ellison, who became famous as author of the National Book Award winning novel Invisible Man in 1953. Though most easily seen as a narrative about race relations and identity in the United States, it is also "a book about the human race stumbling down the path to identity." Ellison's work, and commentary about his work and life, illustrate piety.

- Ralph Ellison, The Collected Essays of Ralph Ellison (Modern Library, 1995).

- Arnold Rampersad, Ralph Ellison: A Biography (Knopf, 2007).

- Beth Eddy, The Rites of Identity: The Religious Naturalism and Cultural Criticism of Kenneth Burke and Ralph Ellison (Princeton University Press, 2003).

Technical and Analytical Readings

On reverence:

- Paul Woodruff, Reverence: Renewing a Forgotten Virtue (Oxford University Press, 2nd edition, 2014).

- Mike W. Martin, Albert Schweitzer's Reverence for Life: Ethical Idealism and Self-Realization (Routledge, 2016).

- Marvin Meyer, Reverence For Life: The Ethics of Albert Schweitzer for the Twenty-First Century (Syracuse University Press, 2002).

- Kurt D. Fausch, A Reverence for Rivers: Imagining an Ethic for Running Waters (McGill-Queens University Press, 2011).

- David K. Gordon, The New Rationalism: Albert Schweitzer's Philosophy of Reverence for Life (McGill-Queens University Press, 2013).

- Donald A. Crosby, The Thou of Nature: Religious Naturalism and Reverence for Sentient Life (State University of New York Press, 2013).

Here are works more directly on the subject of religious naturalism.

- Ursula Goodenough, The Sacred Depths of Nature (Oxford University Press, 1998).

- Jerome A. Stone, Religious Naturalism Today: The Rebirth of a Forgotten Alternative (State University of New York Press, 2008).

- Gordon Kaufman, In the Face of Mystery: A Constructive Theology (Harvard University Press, 1995).

- Thomas Berry, The Sacred Universe: Earth, Spirituality, and Religion in the Twenty-First Century (Columbia University Press, 2009).

- Gregory Bateson, Steps to an Ecology of Mind: Collected Essays in Anthropology, Psychiatry, Evolution, and Epistemology (University of Chicago Press, 2000).

- Gary Snyder and Jim Harrison, The Etiquette of Freedom: Gary Snyder, Jim Harrison, and The Practice of the Wild (Counterpoint, 2010).

- Gary Snyder, The Practice of the Wild: Essays (Counterpoint, 2010).

Photographs

Documentary and Educational Films

Imaginary

Fictional Narratives

Gary Snyder is a Pulitzer Prize winning poet whose focus on ecology was informed by Zen Buddhism. His works illustrate a naturalistic conception of piety.

- Gary Snyder, The Gary Snyder Reader: Prose, Poetry, and Translations (Counterpoint, 1999).

- Gary Snyder, Turtle Island (New Directions, 1974): “Snyder's poems fall roughly into three categories: lyrical precepts (prayers, spells, charms) designed to instill an ‘ecological conscience’ so that we will respect the otherness of nature, frequently personified as the tender, generative mother, and use her wisely.”

- Gary Snyder, Riprap and Cold Mountain Poems (Counterpoint, 2009): “Snyder’s poems draw parallels between nature and language and illustrate abstracts of metaphysical philosophy. This complex poem describes the nature of all things. Snyder’s tone is close to that of a spectator that is merely observing his surroundings.”

- Gary Snyder, Mountains and Rivers Without End (Counterpoint, 2008): “. . . Snyder's new book is full of references to the Native American and Chinese myths and ecological concerns that characterize his work. It also touches on his years spent as a Yosemite mountaineer and trail worker, as well as his decade studying Buddhism in Japan.”

- Gary Snyder, No Nature: New and Selected Poems (Pantheon, 1993).

- Gary Snyder, The Back Country (New Directions, 1971): “This collection is made up of four ‘Far West’―poems of the Western mountain country where, as a young man. Gary Snyder worked as a logger and forest ranger . . .”

Poetry

My heart leaps up when I behold

A rainbow in the sky:

So was it when my life began;

So is it now I am a man;

So be it when I shall grow old,

Or let me die!

The Child is father of the Man;

And I could wish my days to be

Bound each to each by natural piety.

[William Wordsworth, “My Heart Leaps Up”]

Why! who makes much of a miracle?

As to me, I know of nothing else but miracles,

Whether I walk the streets of Manhattan,

Or dart my sight over the roofs of houses toward the sky,

Or wade with naked feet along the beach, just in the edge of the water,

Or stand under trees in the woods,

Or talk by day with any one I love—or sleep in the bed at night

with any one I love,

Or sit at table at dinner with my mother,

Or look at strangers opposite me riding in the car,

Or watch honey-bees busy around the hive, of a summer forenoon,

Or animals feeding in the fields,

Or birds—or the wonderfulness of insects in the air,

Or the wonderfulness of the sun-down—or of stars shining so

quiet and bright,

Or the exquisite, delicate, thin curve of the new moon in spring;

Or whether I go among those I like best, and that like me best—mechanics,

boatmen, farmers,

Or among the savans—or to the soirée—or to the opera.

Or stand a long while looking at the movements of machinery,

Or behold children at their sports,

Or the admirable sight of the perfect old man, or the perfect old woman,

Or the sick in hospitals, or the dead carried to burial,

Or my own eyes and figure in the glass;

These, with the rest, one and all, are to me miracles,

The whole referring—yet each distinct and in its place.

To me, every hour of the light and dark is a miracle,

Every cubic inch of space is a miracle,

Every square yard of the surface of the earth is spread with the same,

Every foot of the interior swarms with the same;

Every spear of grass—the frames, limbs, organs, of men and women, and all that

concerns them,

All these to me are unspeakably perfect miracles.

To me the sea is a continual miracle;

The fishes that swim—the rocks—the motion of the waves—the ships,

with men in them,

What stranger miracles are there?

[Walt Whitman, “Miracles”]

Music: Composers, artists, and major works

Like many works of music, Jean Sibelius’ Symphony No. 5 in E-flat Major, Op. 82 (1919) (approx. 28-33’) (list of recorded performances), illustrates several human values. An everyday event – a flock of swans flying overhead – inspired him to compose it. His response to seeing them fly is reminiscent of the observation that everything can be seen as a miracle. Sibelius had been struggling with the symphonic idea itself. “Sibelius was notoriously obsessed with what he called the 'profound logic' of the symphony and the way motifs could evolve organically to form their structure. In 1914 he wrote, 'I should like to compare the symphony to a river. It is born from various rivulets that seek each other, and in this way the river proceeds wide and powerful toward the sea.'” This symphony can be heard to illustrate inspiration and miracles but its center of gravity rests in Sibelius’ response to seeing the birds fly, and in the theme he composed to represent their flight. “On April 21, 1915, Sibelius wrote in his diary, 'Today at ten to eleven I saw 16 swans. One of my greatest experiences. Lord God, that beauty!'” He was responding to nature as Einstein did, with a sense of reverence, or natural piety. That is where a hearing of this theme can put you, and keep you for quite some time. For many listeners, it is unforgettable. Top recorded performances were conducted by Kajanus in 1932, Rodzinski in 1941, Ormandy in 1954, Collins in 1955, Karajan in 1965 ***, Barbirolli in 1966, Davis in 1974, Rattle in 1983, Berglund in 1988, Vänskä in 1996, Mäkelä in 2021, and Collon in 2025.

Olivier Messiaen, Des canyons aux étoiles (From the Canyons to the Stars) (1972) (approx. 90-100’) (list of recorded performances): “. . . Messiaen found the divine presence everywhere in nature, most especially in the songs of birds. All of his compositions reflect the deeply held religious faith that he constantly refreshed in his observations of nature.” “. . . Messiaen transformed his tour of Bryce Canyon and two other monuments of the American West — Cedar Breaks and Zion Park — into sacred music filled with birdsong, sensuous melodies and divine breath.” He wrote: “. . . it is above all a religious work, a work of praise and contemplation. It is also a geological and astronomical work. The sound-colors include all the hues of the rainbow and revolve around the blue of the Stellar’s Jay and the red of Bryce Canyon. The majority of the birds are from Utah and the Hawaiian Islands. Heaven is symbolized by Zion Park and the star Aldebaran.” Excellent performances are by Salonen in 1989, de Leeuw in 1993, Chung in 2001, Gilbert in 2016, and Morlot in 2022.

Stephan Micus “is a genuine music hermit, he composes on his own, records on his own, and plays on his own an infinity of instruments: ranging from sho (the Japanese mouth organ) to ki un ki (the wind instrument used by the Udegeys Siberian tribe), from bodhran (the shamanic Irish drum) to bolombatto (the typical harp from Western Africa), just to mention a few. And always on his own, he records all the voices featured on his records: by using the most advanced multi-track recording techniques to create harmonizations that possess the intact perfume of magic.” His musical output is best grouped in three categories: reverence, living in flow and enlightenment. Most of his albums are best “seen” as expressions of the first value, reverence, a/k/a natural piety. In these albums, Micus contemplates nature, including human nature.”

- “Winter’s End” (2021) (47’): “”Like many Micus albums, Winter’s End has an epic arc to its structure. Thus, ‘Autumn Hymn’ and ‘Winter Hymn’ bookend the program, and songs two and 11, ‘Walking in Snow’ and ‘Walking in Sand,’ both contain an exquisite sense of space punctuated by a solitary 12-string guitar. Between those walks are a ‘Baobab Dance’ of four kalimbas, chikulo, and sinding (a Gambian harp); the ‘Southern Stars’ of four charangos (a Peruvian stringed instrument), five suling (a Balinese flute), a sinding, and two Egyptian nay flutes; and other impressionistic destinations and activities.

- “White Night” (2019) (50’): our lives in context, with track titles including “The Bridge”, “The River”, “Fireflies” and “The Moon”. “From one gate to the other, we embrace the world in the span of 50’, starting the cycle anew. Along the way, we stop to view “The Moon,” wherein a role that might normally have been filled by lone shakuhachi finds a multivalent replacement in the double-reed duduk. Like the nay that appears alongside the Ghanaian dondon (or talking drum) in 'Black Hill,' it is a thought made incarnate by contact of skin and breath. Fitting, then, that Micus’s last name should be an anagram of 'Music,' as his very being is synonymous with that most connective force.”

- “Inland Sea” (2017) (54’) is a landscape portrait, like “White Night”. “While the album's title can refer to possible hospitable climates and civilization, the sparse music nonetheless is much more suggestive of something vast and desolate.” “Micus choruses his voice fifteen times over, and to it adds three genbri, a three-stringed bass instrument from Morocco. Treading the same soil packed by the feet of ‘Dancing Clouds’ (plucked nyckelharpa, 6 percussive nyckelharpa, 3 bowed nyckelharpa, steel string guitar, genbri, bass zither) and laid to rest by ‘For Shirin and Khosru’ (2 bass zithers, 2 nyckelharpa, 3 steel string guitars, genbri), it treats melodic resolution as the caress of a loving parent who dispels fears of darkness. Thus we are protected, hoped for, and fortified to face new days, bringing our own children to the well of mortality, that they might also see the reflections of all who came before them.”

- “Panagia” (2013) (65’): the title refers to Christ’s mother in Christian mythology. The album is a reverential treatment of that which gives life. “If pressed for a comparison, I would say that Panagia resembles Japanese classical gagaku in its arrangement and color, even if it is devoid of gagaku’s exclusivity. Rather, it makes of this big blue ball a royal court where we live not as servants but as purveyors of destiny. Its play of light on reflective surfaces makes it one of the best-recorded albums in the Micus catalogue. It is the meta-statement of a meta-statement, an expression of Gaia through cycles of human thought.”

- “Snow” (2008) (52’) is another musical landscape painting. “Two doussn’gouni (a West African harp that Micus debuted on Desert Poems), along with various gongs and cymbals, give the duduk a gentle berth for travel. Guided by breath, not oar, its intense presence rides toward frosty shores, singing of the ice as gateway and kissing the land with its solemnity.”

- “Desert Poems” (2001) (46’): “Seemingly enamored with the same consuming silence of the desert that captured the heart of writer Paul Bowles, Micus translates the hidden energies of landscape into a form that escapes all measure of mortal grasp.”

- “The Garden of Mirrors” (1997) (50’): “Just as one look at the many instruments Stephan Micus plays is sure to impress, so too does one experience of what he produces with them dispel arbitrary interest in those means. Music flows from his fingertips in such an organic way that the source catches light in all of us.”

- “To the Evening Child” (1992) (46’): “This music sounds in those hushed spaces where the universe inhales, the sound that keeps all celestial bodies spinning.”

- “The Music of Stones” (1989) (51’): “The shakuhachi . . . becomes a woodland creature who knows the trees well enough to skip through the branches blindfolded.”

- “Ocean” (1986) (50’): “Micus lets unfold a territory so personal that it becomes selfless, somehow unmarked the human elements of its creation. In his playing, names, labels, and covers, even personages and politics, cease to matter. The only restriction is its very lack. Such music goes beyond the pathos of meditational action, looking into the soul of stillness, where only music can express that which all the languages of the world, lost and extant alike, never could. Their cage is not one that surrounds us but one we surround with the promise of creation, waiting with closed eyes and open hearts.”

- “East of the Night” (1985) (47’)

- “Listen to the Rain” (1983) (43’): a physical and spiritual landscape

- “Behind Eleven Deserts” (1978) (44’)

Compositions:

- Rudolf Komorous, Serenade for Strings (1982) (approx. 13’)

- Aaron Copland, Quiet City (1940) (approx. 10-11’) (list of recorded performances) – reverence for people

- Raga Chayanat usually performed in late evening, is described as a passionate, red-eyed warrior. Performances are by Buddhadev Dasgupta, Venkatesh Kumar, Rajan and Ghulam Ali Khan.

- Eric Whitacre, a capella choral works

- Ingolf Dahl, Hymn (1947) (approx. 10’)

- Xioagang Ye, Mount E’mei, Op. 74 (2016) (approx. 22’), inspired by a mountain in the Sichuan province, which is revered in Buddhist culture, and by folk music from that region

- Ye, Lamura Cuo, Op. 69b (2014) (approx. 13’), a work for violin and orchestra inspired by a lake in Tibet

- Ye, The Silence of Mount Minshan, Op. 73 (2015) (approx. 11’), for string orchestra, inspired by another mountain in Sichuan

- Augusta Read Thomas, Resounding Earth (2012) (approx. 34’) “is scored for nearly three hundred unique bells and other resonant metal objects. The composition of the work, and the selection of the specific bells used in the recording, was completed in close collaboration between Thomas and Third Coast Percussion.”

- John Luther Adams, An Atlas of Deep Time (2022) (approx. 42’) “is Adams at his best: channeling the natural world with a sense of wonder and urgency, letting his reverence speak for itself with subtle activism.” Adams writes that the work “is grounded in my desire, amid the turbulence of human affairs, to hear the older, deeper resonances of the earth.”

- Erland Cooper, “Music for Growing Flowers” (2022) (31’) reflects “Erland’s fascination with music and nature”.

- Erland Cooper, “Sule Skerry” (2019) (42’) “pays homage to the land and in particular its sea. Piano, strings, synths and spoken word combine to create an appreciation for home and peace.”

- Rushil Ranjan, Abi Sampa, & City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra, “Orchestral Qawwali” (2024) (60’): “. . . genre-blurring, choral collaborations and spiritual rapture . . .”

- Jeffrey Nytch, Constellations (1998) (approx. 29’)

- Deborah Cheetham Fraillon, Earth (2024) (approx. 9’) (description with lyrics) - [the composer] writes: “Ultimately the Earth is set apart from its neighbours in this solar system by our humanity. And so, in the process of composing this work I decided to include that which truly defines us—our Voice.”

Albums:

- Ran Blake, “Sonic Temples” (2000) (122’)

- Inkuyo, “Art from Sacred Landscapes” (61’)

- Lillian Fuchs, “Johann Sebastian Bach, 6 Suites, BWV 1007-1012” (1950s) (120’), played on viola

- Klaus Wiese, “In High Places”, with Al Gromer Khan (2019) (48’)

- Miloš Karadaglić, “The Moon & The Forest” (2021) (52’) is an album of new works for guitar and orchestra, (Ink Dark Moon by Joby Talbot, and The Forest by Howard Shore) exuding reverence for nature.

- Sinikka Langeland, “Wolf Runes” (2021) (42’), draws on Finnish folklore to produce an ode to animals and nature. “Few artists embody the spirit of place as resolutely as Langeland and her songs, compositions, poem settings, and arrangements reflect, in different ways, the histories and mysteries of Finnskogen, Norway’s ‘Finnish forest,’ which has long been both her home base and inspirational source.”

- John Luther Adams, “Houses of the Wind” (2022) (53’): “The album is based on a 10-and-a-half-minute recording of an aeolian harp—a string instrument that’s played by the wind—that Adams made in Alaska in 1989. He’s explored the sound of the instrument before on pieces like The Wind in High Places, in which a string quartet emulates the air-driven device. But here, Adams works with the ethereal instrument itself, creating pieces that teeter between serenity, mourning, and hope.”

- David Boulter, “Whitby” (2025) (approx. 24’) “emerges from a profound connection with the desolate beauty of the North Yorkshire coast. Inspired by the evocative imagery of a sunset over Whitby Abbey and the raw power of the crashing waves, the artist translates a sense of stillness and natural drama into a quietly powerful musical meditation.”

Music: songs and other short pieces

- Karl Jenkins, “Benedictus”, from “The Armed Man: A Mass for Peace”, performed by the cellist Hauser

Visual Arts

- Aleksey Savrasov, Summer Landscape with Pine Trees near the River (1878)

- Aleksey Savrasov, On the Volga (1875)

- Aleksey Savrasov, Rainbow (1875)

- Aleksey Savrasov, Spring Day (1873)

- Aleksey Savrasov, Autumn (1871)

- Aleksey Savrasov, After a Thunderstorm (c. 1875)

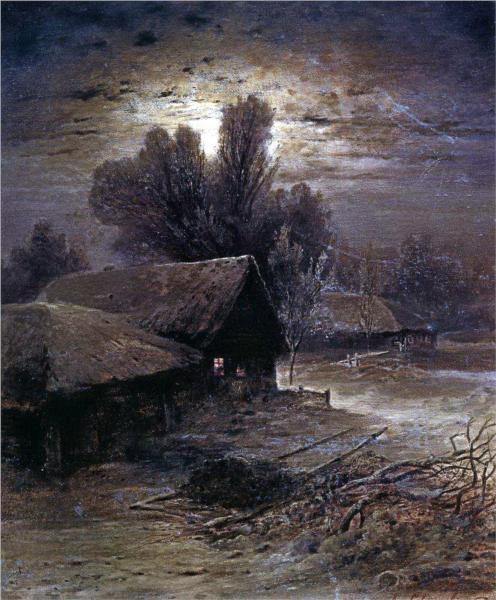

- Aleksey Savrosov, Winter Night (1869)

- Aleksey Savrasov, Summer Landscape (1860s)

- Aleksey Savrasov, Type in the Swiss Alps (1862)