Play is the waking equivalent and active counterpart of a dream; the creative and cathartic activity of non-work. As a dream cleanses the soul, play refreshes the spirit. So much the better when it is done playfully.

Play conveys many benefits. “As behavior, play expresses itself in many forms; it includes objects of innumerable variety. No setting for human activity escapes its reach.” Play exerts significant effects on society and culture. “Play in all its rich variety is one of the highest achievements of the human species, alongside language, culture and technology. Indeed, without play, none of these other achievements would be possible.” Peer-reviewed journals on play include the American Journal of Play, International Journal of Play, and International Journal of Play Therapy.

“Play is of vital importance for the healthy development of children.” “Play is essential to development because it contributes to the cognitive, physical, social, and emotional well-being of children and youth.” “Children need to develop a variety of skill sets to optimize their development and manage toxic stress. Research demonstrates that developmentally appropriate play with parents and peers is a singular opportunity to promote the social-emotional, cognitive, language, and self-regulation skills that build executive function and a prosocial brain. Furthermore, play supports the formation of the safe, stable, and nurturing relationships with all caregivers that children need to thrive.” “When a social-emotional learning (SEL) intervention is implemented in an early childhood classroom, it often involves play.” Play deficiencies in childhood can produce crippling and anti-social tendencies.

Being playful plays an integral role in adult life. “Play and playfulness are clearly more central to adult lives than is commonly supposed . . .” “Among its many benefits, adult play can boost your creativity, sharpen your sense of humor, and help you cope better with stress.” In adults with type 1 diabetes: “Daily play was linked to better mood, greater diabetes disclosure to one’s partner, greater support received from one’s partner, and greater perceived coping effectiveness with the day’s most important diabetes and general stressors.” Journal of Play in Adulthood is devoted to exploring this subject.

Real

True Narratives

- Joe L. Frost, A History of Children’s Play and Play Environments: Toward a Contemporary Child-Saving Movement (Routledge, 2009).

- Howard P. Chudacoff, Children at Play: An American History (New York University Press, 2009).

- Sabine Frühstück and Anne Walthall, eds., Child’s Play: Multi-Sensory Histories of Children and Childhood in Japan (University of California Press, 2017).

Technical and Analytical Readings

- Anthony D. Pellegrini and Peter E. Nathan, eds., The Oxford Handbook of the Development of Play (Oxford University Press, 2010).

- Peter K. Smith & Jaipaul L. Roopnarine, The Cambridge Handbook of Play: Developmental and Disciplinary Perspectives (Cambridge University Press, 2018).

- Dorothy Singer, RobertaMichnik Golinkoff and Kath Hirsh Pasick, Play = Learning: How Play Enhances Children's Cognitive and Social-Emotional Growth (Oxford University Press 2006).

- Vivian Gussin Paley, A Child’s Work: The Importance of Fantasy Play (University of Chicago Press, 2005).

- Stuart Brown and Christopher Vaughan, Play: How It Shapes the Brain, Opens the Imagination and Invigorates the Soul (Avery, 2009).

- David Elkind, The Power of Play: Learning What Comes Naturally (Da Capo Press, 2006).

- Grant Peterson, Just Ride: A Radically Practical Guide to Riding Your Bike (Workman Publishing, 2012): “No matter how much your bike costs, unless you use it to make a living, it is a toy, and it should be fun.”

- Daniel Goldberg and Linus Larsson, The State of Play: Creators and Critics on Video Game Culture (Seven Stories Press, 2015): “. . . a collection of essays by a variety of academics, bloggers and independent game designers, also chooses for its theme how our ‘digital and real lives collide.’ Its editors . . . are interested in the way in which writing about the video game medium has grown from product criticism to social and political commentary.”

Photographs

Documentary and Educational Films

Imaginary

Fictional Narratives

Foreign correspondent Arthur Ransome, who covered the Bolshevik Revolution but “found revolutionary fervor less exhilarating than taxing,” took up a new career at age 45, writing young adult novels in which “children on holiday in the Lake District of England and elsewhere occupy themselves sailing camping, fishing and playing at pirates.”

- Swallows and Amazons (1930).

- Swallowdale (1931).

- Peter Duck: A Treasure Hunt in the Caribbees (1932).

- Winter Holiday (1933).

- Coot Club (1934).

- Pigeon Post (1936).

- We Didn’t Mean To Go To Sea (1937).

- Secret Water (1939).

- The Big Six (1940).

- Missee Lee (1941).

- The Picts and the Martyrs; or Not Welcome At All (1943).

- Great Northern? (1947).

Other novels:

- Jake Tapper, The Devil May Dance: A Novel (Little, Brown and Company, 2021): “The seriousness of this book never gets in the way of the breathless fun. Tapper obviously enjoyed sourcing it, writing it and using can-you-top-this gamesmanship from start to finish.”

Poetry

Music: Composers, artists, and major works

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Die Zauberflöte (The Magic Flute), K. 610 (1791) (approx. 122-158’) (libretto): “Generations of spectators have been fascinated by the melodies and adventures of Papageno, the Queen of the Night, Tamino, and Pamina, the ordeals faced by the young lovers, and the work’s inexhaustible allegorical depth.” “On one level, The Magic Flute is a simple fairy tale concerning a damsel in distress and the handsome prince who rescues her. Beneath the surface, however, the piece is much more complex. It is an allegory of the quest for wisdom and enlightenment as presented through symbols of Freemasonry . . .” “The opera is an allegory concerning the struggle between The Queen of the Night, representing darkness and repression of knowledge, and Sarastro, an enlightened benevolent monarch whose rule is based on wisdom and reason. Tamino and Papageno struggle by trial and error between these opposing forces to find a heaven on Earth and enduring love. The fable is both profound and fantastical . . .” Musically, Mozart makes an extended joke out of it. Best audio-recorded performances are by Lemnitz & Rosvaenge (Beecham) in 1938; Kunz & Loose (Karajan) in 1950; Streich & Stader (Fricsay) in 1955; Gedda & Janowitz (Klemperer) in 1964; Lear & Peters (Böhm) in 1964 ***; Burrows & Prey (Solti) in 1969; Price & Serra (Colin Davis) in 1984; Hendricks & Allen (Mackerras) in 1991; Mannion & Dessay (Christie) in 1995; Röschmann & Strehl (Abbado) in 2005; Behle & Peterson (Jacobs) in 2009; Jo & Sigmundsson (Östman) in 2015; and Vogt & Karg (Nézet-Séguin) in 2019. Here are performances, with video, conducted by Ivan Fischer in 2001 and Stein in 1971.

Along the same line as Mozart’s Magic Flute is Michael Tippett, The Midsummer Marriage (1952) (approx. 148-158’) (libretto).

Playful short romps on piano or, better still, a fortepiano of Beethoven’s era:

- Ludwig van Beethoven, 7 Bagatelles, Op. 33 (1802) (approx. 19-21’)

- Beethoven, 11 New Bagatelles, Op. 119 (1822) (approx. 15’)

- Beethoven, 6 Bagatelles, Op. 126 (1823) (approx. 14-20’)

Other works:

- Playful marches (1899-1914) (approx. 37’) by Julius Fučík

- François de Fossa, Guitar Trios, Op. 18 (approx. 78’): being playful, with others

- Arnold Bax, In the Faery Hills (1909) (approx. 15’)

- Georges Bizet, Jeux D'Enfants (Children's Games), Op. 22 (1871) (approx. 22-23’)

- Works of Ryan Latimer, represented here: his music has been described as “deliciously playful”

- Franz Berwald, Symphony No. 2 in D Major, "Sinfonie Capricieuse" (1842) (approx. 32’)

- Ernst von Gemmingen, Violin Concerti: No. 3 in D Major (1800) (approx. 23’); No. 4 in A Major (1800) (approx. 29’)

- Raga Kirvani (Kirwani) (Keerwani) (Keervani) is a Hindustani classical raag for late evening. Adapted from a Carnatic ragam, it is “playful in nature”. Performances are by Shivkumar Sharma & Hariprasad Chaurasia, Shivkumar Sharma & Zakir Hussain, Hariprasad Chaurasia, Manish Vyas & Bishramjit Singh, and Ali Akbar Khan.

- Raga Khamaj is a Hindustani classical raag for late evening. “The Khamaj terrain ranges over all manner of melodic twists and turns and has been extensively mined.” “Many ghazals and thumris are based on Khamaj”, which “depicts a Chanchal (Playful) nature.” Linked performances are by Nikhil Banerjee in 1984, Vilayat Khan, and Budhaditya Mukherjee in 1997.

- Barbara Harbach, Cuatro Danzas for Flute and Piano (2018) (approx. 14’)

- Joel Feigin, Aviv: Concerto for Piano and Chamber Orchestra (2009) (approx. 19-20’) “suggests the warmth and optimism of the coming of spring.”

Adrian Rollini played bass saxophone during the Roaring 20s (“Adrian Rollini and the Golden Gate Orchestra 1924-1927”; “The Goofus Five 1926-1927”) and into the 1930s (“Swing Low - his 26 finest - 1927-1938” [78’]; “Adrian Rollini - 1929-1934” [154’]). He also played “hot fountain pen (like a penny whistle with a couple of added keys), goofus (also known by its maker as a Couesnophone, it has a saxophone shape, but needs no reed and the keys are laid out like a piano keyboard), vibraphone, xylophone, celeste (a keyboard that moves hammers that strike metal bars), harpaphone (what some call ‘bells,’ a metal keyboard played with mallets) and piano.” He may never have played a heavy note.

Albums:

- Jane Ira Bloom, “The Red Quartets” (2021) (61’): “What a pleasure it is to hear a jazz quartet play with such joy and precision.”

- Claude Bolling, “Toot Suite” (1980) (37’): “. . . parts of Toot Suite are overrun with a terminal case of the 'cutes' . . .”

- Claude Bolling, “Picnic Suite” (1979) (37’)

- Stephen Riley, “Oleo” (2019) (67’)

- Joe Fiedler, “Fuzzy and Blue: Open Sesame” (2021) (63’): “. . . Fiedler gives the music of Sesame Street a spin around the creative music block.”

- Kirk Knuffke & Harold Danko, “Play Date” (2019) (64’) is about playing nice. “There’s an affirming rapport in the way neither man crowds the other and instead allows the shared narratives to develop naturally without even a modicum of artifice.”

- Camille Bertault & David Helbock, “Playground” (2022) (52’) exhibits play as creation. “. . . Bertault’s live-wire humour and Helbock’s calm self-assuredness only appear different on the surface. When it comes to the musical choices they make, they are emphatically on the same page.”

- Andy Findon & Geoff Eales, “The Dancing Flute: The flute and piano music of Geoff Eales” (2013) (63’) is “fleet of foot and light of spirit . . .” Findon describes it as “a celebration of the life-enhancing qualities of the dance”.

Music: songs and other short pieces

- The Beatles, “Ob-La-De, Ob-La Da” (lyrics)

- Cindy Lauper, “Girls Just Want to Have Fun” (lyrics)

- David Guetta, “Play Hard” (lyrics)

- Jennifer Lopez, "Play" (lyrics)

- Franz Schubert (composer), Die Forelle (The Trout), D. 550 (1817) (lyrics)

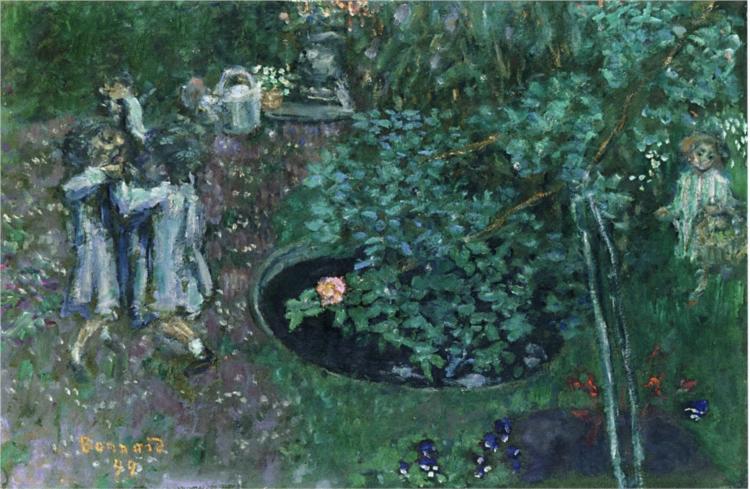

Visual Arts

- Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Girl with a Hoop (1885)