Being precise is a part of conforming to the order that is all around us, and within us.

- A page of a book, he noted, cannot be absorbed in one stare; you need to go word by word. “If you wish to have a sound knowledge of the forms of objects, begin with the details of them, and do not go on to the second step until you have the first well fixed in memory.” [Walter Isaacson, Leonardo da Vinci, p. 520.]

- Be precise. A lack of precision is dangerous when the margin of error is small.[Donald Rumsfeld]

- Laws must be clear, precise, and uniform for all citizens. [Marquis de Lafayette]

Uncommon precision also characterizes transcendence. Though genius transcends mere precision, and is most often associated with creativity, we should not ignore its harmonic component, which distinguishes the genius from the crackpot.

Real

True Narratives

Book narratives:

- Simon Winchester, The Perfectionists: How Precision Engineers Created the Modern World (Harper/HarperCollins Publishers, 2018): “From the Industrial Revolution until today, the pursuit of precision shapes everything

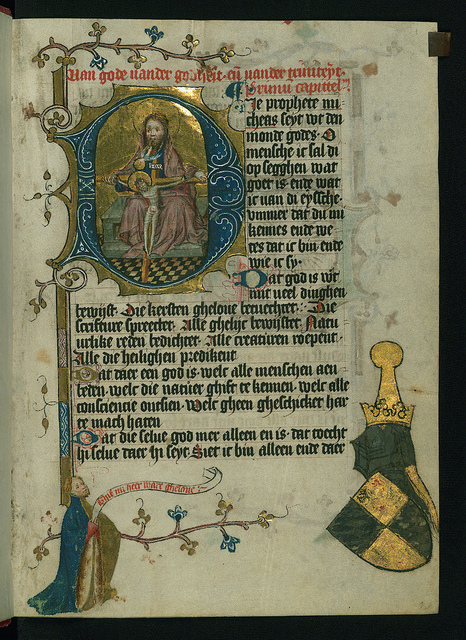

The medieval church placed a high value on precision, to a fault. However, the illuminated manuscripts from that period illustrate the important value of precision and detail.

- Edward Quaile, Illuminated Manuscripts: Their Origin, History and Characteristics (Henry Young and Sons, 1897).

- Raymond Clemens and Timothy Graham, Introduction to Manuscript Studies (Cornell University Press, 2007).

- Thomas Kren, Illuminated Manuscripts of Belgium and the Netherlands at the J. Paul Getty Museum (Getty Publications, 2010).

- Thomas Kren, Illuminated Manuscripts of Germany and Central Europe in the J. Paul Getty Museum (Getty Publications, 2009).

- Margaret Morgan, The Bible of Illuminated Letters: A Treasury of Decorative Calligraphy (Barron Educational Series, 2006).

- Rowan Watson, Illuminated Manuscripts and Their Makers (V & A, 2003).

Technical and Analytical Readings

Photographs

Documentary and Educational Films

Imaginary

Fictional Narratives

Poetry

Books of poems:

- Louise Glück, Winter Recipes from the Collective: Poems (Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2021): “Louise Glück’s Stark New Book Affirms Her Icy Precision”.

Music: Composers, artists, and major works

Martha Argerich is an Argentinian classical pianist, whose personal life is somewhat peculiar, as is that of many geniuses. Her daughter made a film about it, called “Bloody Daughter” (2012). Her pianism is entirely another matter. “Some musicians play as if they are making the music up on the spot. It’s an elusive gift. To convey this degree of spontaneity, to give the impression that you’re creating something in the heat of the moment, requires two things. First, such freedom takes consummate musical understanding and mastery of an idiom. Some musicians seem to live the music as they play it, while others strive for a preconceived ideal where, all being well, one performance will be as close to that ideal as the next. Artists like Martha Argerich still have a clear vision and a fully formed interpretation, and are no less perfectionist, but they embrace a more responsive creativity and the possibility of making a connection that is unique to a specific moment.” “There’s something ineffable about her musical understanding and sensitivity, an acute awareness of pacing and rubato (which in other hands would sound contrived) and a glorious range of sound. Martha Argerich brings music to life with an unmatched colour and vibrancy, and an amazing naturalness which speaks of a life spent immersed in the repertoire. She combines power and grace, unafraid to take risks to the point that sometimes her playing seems on the verge of being slightly out of control, which makes it doubly thrilling, yet her playing is impressively precise.” Here is a link to her playlists.

Arturo Benedetti Michalangeli was a classical pianist known for his demanding and exacting approach to pianism. “According to his wife’s memoirs, Michelangeli drew a parallel between playing the piano and being a waiter. ‘Waiters carry trays full of glasses with 2 hands and all goes well. But a pebble is enough to make them trip and cause everything to drop.’ The 'pebble' was the piano itself . . .” “Like the princess distracted by the small pea buried under 14 mattresses, Michelangeli’s hypersensitive fingers and exacting ears could ascertain the tiniest imperfections in a piano’s action, tuning, or voicing. ‘No piano in the world,’ he supposedly claimed, ‘is good enough for Ravel’s Gaspard de la nuit.’” On his recordings, “the elevated beauty and poetry of his playing – and its superhuman precision – are never in any doubt”. And yet: “If there was a disembodied quality to his playing, it was also visceral, and allowed nothing to stand in the way of musical expression. Michelangeli conjured music as much as he played it; it seemed to spring whole from his psyche at the moment of performance.” Here is a link to his playlists.

Rudolf Serkin too was a classical pianist known for his musical precision, and clarity. Here is a link to his playlists.

Conductor Arturo Toscanini “was tyrannical in his demand for orchestral precision . . .” “He demanded precise playing and was plunged into despair over a single lapse. He insisted that any musician, no matter how famous, who did not share his attitude be fired. He would sooner quit than tolerate the slightest lapse in standards.” “Toscanini believed that it was his job—his duty, if you will—to perform the classics with note-perfect precision, singing tone, unflagging intensity, and an overall feeling of architectural unity that became his trademark.” “It is often said that Toscanini's readings only seemed fast due to their extreme precision and transparent sonority.” Books about this great man are by Samuel Antek, Harvey Sachs, Cesare Civetta, and Kenneth A. Christensen. His letters are preserved in book form. His playlists are extensive, and many videos capture the maestro at work, on video, such as in this live television broadcast from 1948.

Johann Sebastian Bach’s Six Partitas for Harpsichord, BWV 825-830 (1725-1730) (approx. 145-150’) (list of recorded performances), seem to elicit a special attention to detail in the performers. The listener who is drawn to think of the virtue of precision will not be wrong. Here are links to complete performances of the six partitas by Scott Ross in 1989, Christophe Rousset in 1993, Trevor Pinnock in 1989-1995, Benjamin Alard in 2010, Asako Ogawa in 2020, Mahan Esfahani in 2021, and Celine Frisch on harpsichord; Martin Helmchen in 2024 on tangent piano; and Igor Levit in 2014, Yuan Sheng in 2017, and Eleanor Bindman in 2022 on piano. Links to performances of individual partitas follow here:

- Partita No. 1 in B-flat Major, BWV 825 (approx. 16-20’)

- Partita No. 2 in C minor, BWV 826 (approx. 20-21’)

- Partita No. 3 in A minor, BWV 827 (approx. 19-20’)

- Partita No. 4 in D Major, BWV 828 (approx. 31-35’)

- Partita No. 5 in G Major, BWV 829 (approx. 21-26’)

- Partita No. 6 in E minor, BWV 830 (approx. 30-34’)

All music has a mathematical foundation. Electronic music is generated by mathematical calculations.

- Examples of electronic groove music include Squarepusher, “Big Loada” (1997) (29’); Autechre, “LP5” (1998) (76’) and “Tri Repetae” (1995) (73’); Four Tet, “Rounds” (2003) (75’); Geogaddi, “Boards of Canada” (2002) (76’); Boards of Canada, “Music Has the Right to Children” (1998) (71’); and various artists, “Selected Ambient Works 85-92” (1992) (75’).

Precision in playing:

- Avishai Cohen Trio, “Shifting Sands” (2022) (51’)

Music: songs and other short pieces

Visual Arts

Film and Stage

- In Ivan the Terrible, the filmmaker Sergei Eisenstein arranged every frame with “with the eye of a painter or choreographer.” That cinematic attention to detail is my reason for offering this film to illustrate precision.