- When I was a boy of 14, my father was so ignorant I could hardly stand to have the old man around. But when I got to be 21, I was astonished at how much the old man had learned in seven years. [Attributed, perhaps falsely, to Mark Twain.

Reconsidering is an aspect of being open. By reconsidering, we can learn from our mistakes, adapt to change, make better decisions, expand our horizons, and build resilience. A habit or practice of reconsideration may lead to positive emotion.

Real

True Narratives

- Jeanette Winterson, Why Be Happy When You Could Be Normal? (Grove Press, 2012), a memoir about the author’s Pentecostal upbringing that “wrings humor from adversity . . . but the ghastly childhood transfigured there is not the same as the one vivisected here in search of truth and its promise of setting the cleareyed free.”

- Vivian Gornick, Unfinished Business: Notes of a Chronic Re-Reader (Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2020): “. . . an urgent argument that rereading offers the opportunity not just to correct and adjust one’s recollection of a book but to correct and adjust one’s perception of oneself.”

- Menachem Kaiser, Plunder: A Memoir of Family Property and Nazi Treasure (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2021): “‘Plunder’ has many moods and registers. It acquires moral gravity. It pays tender and respectful attention to forgotten lives. It is also alert to melancholic forms of comedy.”

- Annette Gordon-Reed, On Juneteenth (Liveright, 2021): “Gordon-Reed acknowledges that origin stories matter, even if they often have more to say about ‘our current needs and desires’ than with the facts of history, which are often stranger and less assimilable than any self-serving mythology will allow.”

- Erika Krouse, Tell Me Everything: The Story of a Private Investigation (Flatiron, 2022): “She Became a Private Eye. And Investigated Her Past.”

- Sly Stone with Ben Greenman, Thank You (Fallenntinme Be Mice Elf Agin): A Memoir (AUWA, 2023): “His response to other people telling his story and analyzing his struggles: 'They’re trying to set the record straight. But a record’s not straight, especially when you’re not. It’s a circle with a spiral inside it. Every time a story is told it’s a test of memory and motive. … It isn’t evil but it isn’t good. It’s the name of the game but a shame just the same.'”

- Susan Neiman, Learning from the Germans: Race and the Memory of Evil (Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2019): “Neiman contends that postwar Germany, after initially stumbling badly, has done the hard work necessary to grapple with and come to terms with the legacy of the Holocaust in a way that could be a lesson to America in general, and the American South in particular.”

Technical and Analytical Readings

Photographs

Documentary and Educational Films

- 51 Birch Street: after a man’s mother dies and his father plans to move to Florida with his former secretary, his mother’s diary reveals some unsettling facts about the couple’s 54-year marriage

Imaginary

Fictional Narratives

Novels:

- Jeffrey Eugenides, The Marriage Plot: A Novel (Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2011): “. . . the novel isn’t really concerned with matrimony or the stories we tell about it, and the title, the opening glance at Madeleine’s library and the intermittent talk of books come across as attempts to impose an exogenous meaning. The novel isn’t really about love either, except secondarily. It’s about what Eugenides’s books are always about, no matter how they differ: the drama of coming of age.”

- Alexander Starritt, We Germans: A Novel (Little, Brown & Co., 2020): “Meissner offers a layered meditation on the ideology of the Nazi Party, and on what his actions say about him as a human.” (Germans holding themselves accountable for Nazism)

- Jon Fosse, Septology I-VII (Transit Books, 2023); [I-II; III-V; VI-VII] (Transit Books, 2020-22): “. . . an extraordinary seven-novel sequence about an old man’s recursive reckoning with the braided realities of God, art, identity, family life and human life itself . . .”

- Joseph Kanon, The Berlin Exchange: A Novel (Scribner, 2022): “Martin once believed he was working for the greater good, but now wonders whether any side is worth his loyalty.”

Poetry

Music: Composers, artists, and major works

Felix Mendelssohn, Symphony No. 3 in A Minor, Op. 56, “Scottish” (1842) (approx. 39-44’), was inspired by the composer’s experiences in Scotland. “We went, in the deep twilight, to the Palace of Holyrood, where Queen Mary lived and loved. There’s a little room to be seen there, with a winding staircase leading up to it. This the murderers ascended, and finding Rizzio, drew him out. Three chambers away is a small corner where they killed him. Everything around is broken and moldering, and the bright sky shines in. I believe I found today in the old chapel the beginning of my Scottish Symphony.” “The actual composition of the Scottish Symphony was not completed until thirteen years after his Scottish journey making it, despite its designation as Symphony No 3, the last of his five symphonies. He returned to the work on occasions throughout the 1830s but found it difficult to recreate his ‘Scotch mood’ and it was only in 1842 that the work received its first performance in Leipzig, being repeated in London in the same year to an audience that included the young Queen Victoria, to whom the symphony is dedicated.” “As we can readily hear in the Scottish Symphony, Mendelssohn’s ‘travel music’ really does suggest the landscapes and cultures that inspired it. The symphony’s first movement is grand and joyful, with a briskness and energy that seem true to Scotland. This effect is even more marked in the lively second movement, which evokes the tunes and rhythms of Scottish folk music without directly quoting from Scottish sources. The contemplative third movement gives way to an energetic finale that draws from the rhythms of Scottish folk dances. In an elevated, German-style coda, Mendelssohn seems to conclude the symphony with a Scottish-German alliance of his own invention.” Top recorded performances are conducted by Toscanini in 1941, Rodzinski in 1947, Maag in 1957, Munch in 1958, Klemperer in 1960, Karajan in 1971, Bernstein in 1979, Harnoncourt in 1992 ***, Ashkenazy in 1999, Colin Davis in 2004, Litton in 2009, Chailly in 2009, Gardner in 2014, and Orozco-Estrada in 2020.

Other compositions:

- Alexander Glazunov, Suite Caractéristique in D Major, Op. 9 (1887) (approx. 31-34)

- Boris Lyatoshynsky, Symphony No. 5 in C Major, Op. 67, “Slavonic” (1966) (approx. 24-27’), “gazes backward through ancient Slavic history by its use of folk tunes from Russia, Bulgaria and Yugoslavia.”

- Johannes Hieronymus Kapsberger, lute works: Lutenist Paul O’Dette observes that Kapsberger’s contemporaries labeled his work as “unbelievably poor”, “inept trifles . . . bungling and unmelodious.” O’Dette, who performs these works brilliantly, calls Kapsberger “a pearl distorted.”

- César Franck, Prélude, Chorale & Fugue for Piano, M21 (1884) (approx. 20’)

- John Carbon, Six Spanish Lessons (1988) (approx. 18’); Six More Spanish Lessons (2001) (approx. 14’)

- Carbon, Piano Sonata (2009) (approx. 22-24’)

- Michael Tilson Thomas, Upon Further Reflection (1963-1977) (approx. 25’), “. . . is a three-movement meditation on the artist’s early life . . .”

- Joan Tower, Still/Rapids (2013/1996) (approx. 17’): “'Still' was written later as an introduction to 'Rapids' because I felt that the fast-paced and busy ‘Rapids’ might be helped by a short, slow and simpler soft piece.”

- Anthony Iannoccone, “From Time to Time”, Fantasias on Two Appalachian Folksongs (2000) (approx. 16’), reflects “the composer’s research into Virginia’s history . . . The first movement concerns the past, moving from conflict to resolution. . . The final 'Moving Time: A Millennium Ride' has been described by the composer as 'a fast launch into a new millennium.' We hear the folksong ('Shenandoah') very obviously, but . . . in both movements, Iannaccone reverses the traditional trajectory of theme and variations by holding back on statements of the theme until we have heard variations.”

- Ottorino Respighi, Poema Autunnale for violin & orchestra (1925) (approx. 13-15’)

Piano music of Karol Szymanowski (1882-1937):

- 3 Métopes (3 Poèms), M31, Op. 29 (1915) (approx. 16-20’)

- 4 Études (4 Studies), M3, Op. 4 (1902) (approx. 11-13’)

- 4 Polish Dances, M60 (1926) (approx. 9’)

- 9 Preludes, M1, Op. 1 (1900) (approx. 19-20’)

- 12 Études (12 Studies), M34, Op. 33 (1916) (approx. 14’)

- 20 Mazurkas, M56, Op. 50 (1925) (approx. 48-52’); and 2 Mazurkas, M73, Op. 62 (1934) (approx. 6’); Opp. 50 and 62

- Fantasy in C major, M13, Op. 14 (1905) (approx. 12-16’)

- Masques (Masks), 3 Pieces, M35, Op. 34 (1916) (approx. 21-23’)

- Piano Sonata No. 1 in C Minor, M8, Op. 8 (1904) (approx. 26-28’)

- Piano Sonata No. 2 in A Major, M25, Op. 21 (1911) (approx. 25-28’)

- Piano Sonata No. 3, M38, Op. 36 (1917) (approx. 18-25’)

- Prelude and Fugue in C-sharp Minor, M19 (1905, 1909) (approx. 8’)

- Variations in B-flat Minor, M5, Op. 3 (1903) (approx. 10-12’)

- Variations on a Polish Folk Theme in B Minor, M10, Op. 10 (1904) (approx. 16-23’)

Albums:

- Apocalyptica, “Amplified: A Decade of Reinventing the Cello” (2006) (100’)

- Christen Lien, “Elpis” (2017) (55’): “What will we remember? Who does hindsight blame? If I tell you all that happened, you may not see the same.” (From the composer’s poetry and liner notes with the album.)

- Gabriel Akhmad Marin, “Ruminate” (2021) (46’): an improvisational album on which the artist “amalgamates numerous Silk Road musical instruments and genres that are rooted in the traditions of distinct regional performance-practices yet infused with melodic phrasings and strumming techniques spanning across Eurasia”

- Voces8, “Home” (2023) (73’) is a selection of Eric Whitacre’s choral works over a thirty-year composing career, suggesting his return home. “The sound from the choir's own Voces8 Centre is superb.”

- John Abercrombie (with Marc Johnson, Peter Erskine & John Surman), “November” (1992) (69’): “Named for both the month its was recorded in and for the mood it maintains . . . (the album is) a cloudy and sometimes pensive set of mostly group originals.”

- Anouar Brahem, “Khomsa” (1994) (76’) “is a beautiful contemporary statement reflecting the cinematic forms Brahem loves, mixed with European classical and improvisational sensibilities, professionally rendered, and well within the tradition of world jazz and the clean ECM concept.”

- BlankFor.ms, Jason Moran & Marcus Gilmore, “Refract” (2023) (62’): “Digital timbres swiftly change from squelchy and rhythmic to gaseous and choral, giving the set a series of shifts and pivots that take it from gently skewed dance riffs to lush ambient dreamscapes . . .”

- John Francis Flynn, “Look Over the Wall, See the Sky” (2023) (43’) “affirms his striking ability to reimagine storied traditional songs through a darkly distorting 21st-century filter.” “These are old songs, old sounds, old words. But in Flynn’s hands, they are transformed, the work of an artist revisiting foundational texts not to revive the past, but to process the present by imagining a different one.”

- Enrico Pieranunzi, Marc Johnson & Joey Baron, “Hindsight: Live At La Seine Musicale” (2024) (54’): “Pieranunzi largely avoids the Broadway songbook in favour of original compositions coloured by his deep love and understanding of jazz but also his knowledge of classical and Baroque form, folk and other popular music.”

Music: songs and other short pieces

- John Lennon, “Watching the Wheels” (lyrics)

- Taylor Swift, "All Too Well" (lyrics)

- David Bowie, “Changes” (lyrics)

- Theobald Böhm, Elegie in A-flat Major, Op. 47

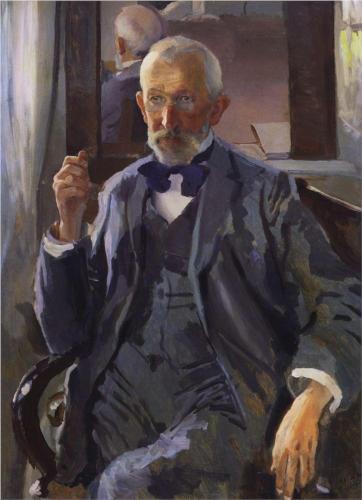

Visual Arts

- Frida Kahlo, Portrait of My Father (1951)

- Salvador Dali, Portrait of My Father (1920)

- Ilya Repin, Portrait of Efim Repin, the Artist's Father (1879)

- Paul Cezanne, The Artist's Mother (1867)

- Paul Cezanne, The Artist's Father Reading His Newspaper (1866)

- Rembrandt van Rijn, Portrait of Rembrandt's Father

- Rembrandt van Rijn, Portrait of Artist's Mother (1639)

Film and Stage

From the shadow side: