There are many kinds of non-violent revolution: in science, education, sports, the arts – in virtually every field of endeavor. When the subject matter is about scarce resources, a revolution can be violent.

- Now, the right of revolution is an inherent one. When people are oppressed by their government, it is a natural right they enjoy to relieve themselves of the oppression. [Ulysses S. Grant]

- A great human revolution in just a single individual will help achieve a change in the destiny of a nation and, further, will enable a change in the destiny of all humankind. [from Daisaku Ikeda, The New Human Revolution.]

People have long sought to oppress other people. That is the main source of the revolutions we think about when we hear that word. However, that is not the only kind of revolution. “There are all sorts of revolutions: political revolutions, economic revolutions, industrial revolutions, scientific revolutions, artistic revolutions . . . but no matter what one changes, the world will never get any better as long as people themselves . . . remain selfish and lacking in compassion. In that respect, human revolution is the most fundamental of all revolutions, and at the same time, the most necessary revolution for humankind.”

Real

True Narratives

On the value of revolution:

- Mike Rapport, The Unruly City: Paris, London and New York in the Age of Revolution (Basic Books, 2017): “The central realization left by Rapport’s book is that the democratic structures that have supported us for so long came about as a result of a series of convulsions of the established order.”

- Elizabeth Hinton, America on Fire: The Untold History of Police Violence and Black Rebellion Since the 1960s (Liveright, 2021): “Recasting ‘Riots’ as Black Rebellions”.

The quest for freedom under a form or semblance of democracy often has been revolutionary.

- Robin Wright, Rock the Casbah: Rage and Rebellion Across the Islamic World (Simon & Schuster, 2011): about the democratic movement that swept the Islamic world in 2011.

- James M. Zimmerman, The Peking Express: The Bandits Who Stole a Train, Stunned the West, and Broke the Republic of China (PublicAffairs, 2023): “Social bandits are, rather, peasant heroes of popular resistance, cheated of their livelihood, exploited and scorned by landlords and power brokers, the nascent revolutionaries who seek justice in the asymmetrical warfare of class struggle.”

- Robert Darnton, The Revolutionary Temper: Paris, 1748-1789 (W.W. Norton & Company, 2023): “In this illuminating study, he presents the outbreak of the revolution in Paris in 1789 as the culmination of 40 years’ worth of political scandals and cultural polemics, which — fueled by a barrage of real and fake news from a diverse range of sources — fostered in the public 'a revolutionary temper that was ready to destroy one world and construct another.'”

In a capitalist world, most labor movements are revolutionary, albeit in varying ways and degrees.

- Ching Kwan Lee, Against the Law: Labor Protests in China's Rustbelt and Sunbelt (University of California Press, 2007).

- Maria Lorena Cook, Organizing Dissent: Unions, the State, and the Democratic Teachers' Movement in Mexico (Pennsylvania State University Press, 1995).

- Joe Foweraker, Popular Mobilization in Mexico: The Teachers' Movement, 1977-87 (Cambridge University Press, 1993).

- Biorn Maybury-Lewis, The Politics of the Possible: The Brazilian Rural Workers' Trade Union Movement, 1964-1985 (Temple University Press, 1994).

Views on the American Revolution:

- Alfred F. Young, Gary B. Nash and Ray Raphael, eds., Revolutionary Founders: Rebels, Radicals, and Reformers in the Making of the Nation (Alfred A. Knopf, 2011).

- Holger Hoock, Scars of Independence: America’s Violent Birth (Crown Publishers, 2017): a narrative focusing on the violence of a revolution.

- Russell Shorto, Revolution Song: A Story of American Freedom (W.W. Norton & Company, 2017): “He writes about six people, all of whom lived in the Revolutionary era, but he does not roll them up into a single narrative or use their lives to bolster an overarching thesis. Instead, he artfully weaves their stories together and leaves it to the reader to draw conclusions.”

- Joseph J. Ellis, The Cause: The American Revolution and Its Discontents 1773-1783 (Liveright, 2021): “The original demand of The Cause (the historical term for the Revolutionary War) was actually conservative: Give us our due rights under British law. Nationhood was not the goal.”

- Gordon S. Wood, Power and Liberty: Constitutionalism and the American Revolution (Oxford University Press, 2021): “Wood is more the champion of the little guy; he is Jefferson to Ellis’s Hamilton. But neither man would maintain that the framers were 'small d' democrats. As Ellis points out, the word 'democracy' back then was more suggestive of mob rule than reasoned deliberation.”

Not all uprisings succeed or are well-conceived but they may achieve their intended effects anyway.

- Tony Horwitz, Midnight Rising: John Brown and the Raid That Sparked the Civil War (Henry Holt & Company, 2011).

- Evan Carton, Patriotic Treason: John Brown and the Soul of America (Free Press, 2006).

- David S. Reynolds, John Brown, Abolitionist: The Man Who Killed Slavery, Sparked the Civil War, and Seeded Civil Rights (Alfred A. Knopf, 2005).

- Joseph Barry, The Strange Story of Harper's Ferry (1903).

Sometimes the revolutionary spirit has found expression in exposes of the government:

- Glenn Greenwald, No Place to Hide: Edward Snowden, the NSA, and the U.S. Surveillance State (Metropolitan Books, 2014),

- Daniel Ellsberg, Secrets: A Memoir of Vietnam and the Pentagon Papers (Penguin, 2002).

- Ward Churchill and Jim Vander Wall, The Cointelpro Papers: Documents from the FBS’s Secret Wars Against Dissent in the United States (South End Press, 1990).

- Tom Wells, Wild Man: The Life and Times of Daniel Ellsberg (Palgrave Macmillan, 2001).

- Daniel Ellsberg, Papers on the War (Simon & Schuster, 1972).

- Betty Medsger, The Burglary: The Discovery of J. Edgar Hoover’s Secret FBI (Alfred A. Knopf, 2014): a first-person account by a woman who broke into an FBI office and exposed illegal FBI activities.

- Jonathan Stevenson: A Drop of Treason: Philip Agee and His Exposure of the CIA (University of Chicago Press, 2021): Agee argued that the CIA was “nothing more than the secret police of American capitalism, plugging up leaks in the political dam night and day so that shareholders of U.S. companies operating in poor countries can continue enjoying the rip-off.”

Revolutions in art and literature:

- Herbert Leibowitz, “Something Urgent I Have to Say to You”: The Life and Works fo William Carlos Williams (Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2011), about the poet, “working furiously over a lifetime to reinvent American poetry . . .”

- Mayukh Sen, Taste Makers: Seven Immigrant Women Who Revolutionaized Food in America (W.W. Norton & Company, 2021): “When we speak of the feats of immigrants, we tend to think of displacement, resilience, resistance, persistence, ingenuity and adaptability; Sen embeds these themes within intimate, individual stories as a way to unravel how his subjects’ achievements — and struggles — have contributed to what and how we eat in America today.”

- Eric Drott, Music and the Elusive Revolution: Cultural Politics and Political Culture in France, 1968–1981 (University of California Press, 2011).

- Amy Nelson, Music for the Revolution: Musicians and Power in Early Soviet Russia (The Pennsylvania State University Press, 2004).

- Paul Merrick, Revolution and Religion in the Music of Liszt (Cambridge University Press, 1987).

- Emily I. Dolan, The Orchestral Revolution: Haydn and the Technologies of Timbre (Cambridge University Press, 2013).

- Val Wilmer, As Serious As Your Life: Black Music and the Free Jazz Revolution, 1957–1977 (Serpent’s Tail, 2018).

- Ales Erjavec, ed., Aesthetic Revolutions and Twentieth-Century Avant-Garde Movements (Duke University Press, 2015).

- Tatiana E. Flores, Mexico's Revolutionary Avant-Gardes: From Estridentismo to ¡30–30! (Yale University Press, 2013).

On the Russian revolution:

- Helen Rappaport, Caught in the Revolution: Petrograd, Russia, 1917 – A World on the Edge (St. Martin’s Press, 2017): “By confining herself to foreigners in Russia’s capital, Rappaport takes a necessarily narrow view of revolutionary history.”

- Sheila Fitzpatrick, The Russian Revolution (Oxford University Press, 4th edition, 2017).

- Mark D. Steinberg, The Russian Revolution, 1905-1921 (Oxford University Press, 2017).

On the Mexican revolution:

- Alan Knight, The Mexican Revolution. Volume 1: Porfirians, Liberals, and Peasants (Cambridge University Press, 1986); Volume 2: Counter-revolution and Reconstruction (University of Nebraska Press, 1990).

- Michael J. Gonzales, The Mexican Revolution, 1910-1940 (University of New Mexico Press, 2002).

On the French revolution:

- William Doyle, The Oxford History of the French Revolution (Oxford University Press, 3rd edition, 2018).

- David Andress, The Oxford Handbook of the French Revolution (Oxford University Press, 2015).

- Thomas Carlyle, The French Revolution: A History (1903).

On the difficulties of revolution, and how revolutions sometimes fail:

- Rachel Aspden, Generation Revolution: On the Front Line Between Tradition and Change in the Middle East (Other Press, 2017): “ An account of an Egyptian revolution, spawned by modern communications technologies, and how it did not hold”.

- Yuri Slezkine, The House of Government: A Saga of the Russian Revolution (Princeton University Press, 2017). “The tale of a Soviet housing complex and the Bolshevik elite that suffered there.”

On the individual-personal aspects of revolution:

- Wael Ghonim, Revolution 2.0: The Power of the People Is Greater Than the People in Power: A Memoir (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2012): “. . . revolution begins with the self: with what one is willing to stand for online and offline, and what one citizen is willing to risk in the service of his country.”

- Stacy Schiff, The Revolutionary: Samuel Adams (Little, Brown and Company, 2022): “What do you call an anti-tax ideologue who spreads false accounts of rape and child murder via the mass media with the explicit goal of bringing down legitimately constituted government? If the man is Samuel Adams, you call him a founder.”

Technical and Analytical Readings

Photographs

Documentary and Educational Films

- Pray the Devil Back to Hell: on the peaceful replacement of Liberian dictator Charles Taylor by “Africa’s first female head of state”

- Malcolm X, on the life of the philosophical counterpart of Martin Luther King, Jr.

- The Battle of Algiers, about the Algerian uprising against French rule

- French Revolution (1789-1799): BBC documentary; Discovery Channel documentary; The Rise and Fall of Versailles series

- Haitian Revolution (1791-1804)

- United Irishmen’s Revolution (1798): “Age of Revolution” on BBC; 1798 Year of Blood, Part 1; Part 2

- Serbian Revolution (1804-1835)

- Greek War of Independence (1821-1832)

- Eureka Revolution (1854)

- Taiping Revolution (1850-1864)

- Mexican Revolution (1910-1920)

- Russian Revolution (1917)

- China in Revolution (1911-1949) and (1949-1976)

- Cuban Revolution (1959)

American Revolution (1765-1783) documentaries:

- PBS series, Part 1; Part 2

- History Channel series

- Discovery Channel series, Part 1; Part 2

- AF Channel series

Imaginary

Fictional Narratives

At that epoch, which was, to all appearances indifferent, a certain revolutionary quiver was vaguely current. Breaths which had started forth from the depths of '89 and '93 were in the air. Youth was on the point, may the reader pardon us the word, of moulting. People were undergoing a transformation, almost without being conscious of it, through the movement of the age. The needle which moves round the compass also moves in souls. Each person was taking that step in advance which he was bound to take. The Royalists were becoming liberals, liberals were turning democrats. It was a flood tide complicated with a thousand ebb movements; the peculiarity of ebbs is to create intermixtures; hence the combination of very singular ideas; people adored both Napoleon and liberty. We are making history here. These were the mirages of that period. Opinions traverse phases. Voltairian royalism, a quaint variety, had a no less singular sequel, Bonapartist liberalism. [Victor Hugo, Les Misérables (1862), Volume III – Marius; Book Fourth – The Friends of the A B C, Chapter I, “A Group which barely missed becoming Historic”.]

Of what is revolt composed? . . . . Irritated convictions, embittered enthusiasms, agitated indignations, instincts of war which have been repressed, youthful courage which has been exalted, generous blindness; curiosity, the taste for change, the thirst for the unexpected, the sentiment which causes one to take pleasure in reading the posters for the new play, and love, the prompter's whistle, at the theatre; the vague hatreds, rancors, disappointments, every vanity which thinks that destiny has bankrupted it; discomfort, empty dreams, ambitions that are hedged about, whoever hopes for a downfall, some outcome, in short, at the very bottom, the rabble, that mud which catches fire,--such are the elements of revolt. That which is grandest and that which is basest; the beings who prowl outside of all bounds, awaiting an occasion, bohemians, vagrants, vagabonds of the cross-roads, those who sleep at night in a desert of houses with no other roof than the cold clouds of heaven, those who, each day, demand their bread from chance and not from toil, the unknown of poverty and nothingness, the bare-armed, the bare-footed, belong to revolt. Whoever cherishes in his soul a secret revolt against any deed whatever on the part of the state, of life or of fate, is ripe for riot, and, as soon as it makes its appearance, he begins to quiver, and to feel himself borne away with the whirlwind. [Victor Hugo, Les Misérables (1862), Volume IV – Saint-Denis; Book Tenth – The 5th of June, 1832, Chapter I, “The Surface of the Question”.]

In the fifteenth century everything changes.

Human thought discovers a mode of perpetuating itself, not only more durable and more resisting than architecture, but still more simple and easy. Architecture is dethroned. Gutenberg’s letters of lead are about to supersede Orpheus’s letters of stone. / _The book is about to kill the edifice_. / The invention of printing is the greatest event in history. It is the mother of revolution. It is the mode of expression of humanity which is totally renewed; it is human thought stripping off one form and donning another; it is the complete and definitive change of skin of that symbolical serpent which since the days of Adam has represented intelligence. / . . . from the moment when architecture is no longer anything but an art like any other; as soon as it is no longer the total art, the sovereign art, the tyrant art,—it has no longer the power to retain the other arts. So they emancipate themselves, break the yoke of the architect, and take themselves off, each one in its own direction. Each one of them gains by this divorce. Isolation aggrandizes everything. Sculpture becomes statuary, the image trade becomes painting, the canon becomes music. One would pronounce it an empire dismembered at the death of its Alexander, and whose provinces become kingdoms. / Hence Raphael, Michael Angelo, Jean Goujon, Palestrina, those splendors of the dazzling sixteenth century. / Thought emancipates itself in all directions at the same time as the arts. The arch-heretics of the Middle Ages had already made large incisions into Catholicism. The sixteenth century breaks religious unity. Before the invention of printing, reform would have been merely a schism; printing converted it into a revolution . . . . / A book is so soon made, costs so little, and can go so far! How can it surprise us that all human thought flows in this channel? This does not mean that architecture will not still have a fine monument, an isolated masterpiece, here and there. We may still have from time to time, under the reign of printing, a column made I suppose, by a whole army from melted cannon, as we had under the reign of architecture, Iliads and Romanceros, Mahabâhrata, and Nibelungen Lieds, made by a whole people, with rhapsodies piled up and melted together. The great accident of an architect of genius may happen in the twentieth century, like that of Dante in the thirteenth. But architecture will no longer be the social art, the collective art, the dominating art. The grand poem, the grand edifice, the grand work of humanity will no longer be built: it will be printed. / And henceforth, if architecture should arise again accidentally, it will no longer be mistress. It will be subservient to the law of literature, which formerly received the law from it. The respective positions of the two arts will be inverted. It is certain that in architectural epochs, the poems, rare it is true, resemble the monuments. In India, Vyasa is branching, strange, impenetrable as a pagoda. In Egyptian Orient, poetry has like the edifices, grandeur and tranquillity of line; in antique Greece, beauty, serenity, calm; in Christian Europe, the Catholic majesty, the popular naïvete, the rich and luxuriant vegetation of an epoch of renewal. The Bible resembles the Pyramids; the Iliad, the Parthenon; Homer, Phidias. Dante in the thirteenth century is the last Romanesque church; Shakespeare in the sixteenth, the last Gothic cathedral. [Victor Hugo, Notre-Dame de Paris, or, The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1831), Volume I, Book Fifth, Chapter II, “This Will Kill That”.]

Gertrude Stein “strove to reshape literary conventions.”

- Ida: A Novel (1941).

- Stanzas in Meditation (1956).

- Tender Buttons (1914).

- 3 Lives (1909).

Poetry

Poems:

- John Keats, “The Fall of Hyperion” (analysis)

Music: Composers, artists, and major works

Dmitri Shostakovich, Symphony No. 11 in G minor, Op. 103 (“The Year 1905”) (1957) (approx. 61-63’) (list of recorded performances), is about a slaughter of innocents under the Tsar. “On January 22 [O.S. January 9], 1905, a date which is remembered as ‘Bloody Sunday,’ thousands of peaceful, unarmed demonstrators marched to St. Petersburg’s Winter Palace. They intended to present a petition to Tsar Nicholas II. Many supported the Tsar and believed that he would help to address their economic, political, and social grievances. Assembled in the square, they sang God Save the Tsar; but a frightened Nicholas II had fled the palace. Inexplicably, the Imperial Guard opened fire, killing around 1,000 protesters and turning the snow red with blood. . . . The Russian Revolution of 1905 set the stage for the rise of the Bolshevik Revolution in 1917 and the birth of the Soviet Union.” “Coming as it did after the Soviet Union had brutally repressed the Hungarian uprising in November 1956, the Symphony struck some listeners as being as much about 1956 as 1905, despite the specificity of the music (though the use of a Polish resistance song might support the notion).” “After the première an elderly lady was overheard saying: ‘Those aren’t guns firing, they are tanks roaring, and people being squashed.’ And when this was related to Shostakovich, he is reported to have replied: ‘That means she understood it.’ Even the composer’s own son apparently asked his father: ‘Papa, what if they hang you for this?’ But he was not hanged. In fact the work was a huge success and resulted in a Lenin Prize for the composer the following year. It is ironic that the symphony should have been so praised by a régime that it was probably secretly denigrating.” Top performances are conducted by Stokowski in 1958, Mravinsky in 1959, Mravinsky in 1967, Kondrashin in 1973, Haitink in 1983, Rostropovich in 2002, Vasily Petrenko in 2009, Wigglesworth in 2010, Gergiev in 2014, Nelsons in 2018, Storgårds in 2020; and Payare in 2020.

Shostakovich, Symphony No. 12 in D minor, Op. 112 (“The Year 1917”) (1961) (approx. 37-40’) (list of recorded performances), generally is not regarded to be among Shostakovich’s best works. “Hardly Shostakovich's most profound or ponderable symphony, ‘The Year 1917’ is in effect almost a cycle of thematically connected mini-tone poems.” This could be because his heart was not in it. This “symphony’s nickname was a calculated political decision in a life-or-death strategy for artistic survival. When he named his Symphony No. 12 ‘The Year 1917,’ it was an emphatic political gesture referencing the year of the Russian Revolution. The symphony itself is a heroic biographical narrative honoring a principal figure of that revolution, Vladimir Lenin. Shostakovich wrote the symphony in 1961, a year after joining the Communist Party, and eight years after the death of Joseph Stalin.” The State had been pressuring him to join the Party. “When the Twelfth Symphony was first heard at the 1962 Edinburgh Festival, the critics were appalled at this crude piece of blatant, poster-painted Soviet propaganda. After all, that was exactly what it sounded like, lacking even the one redeeming feature of the much-maligned Second Symphony, that extraordinary, undisciplined crucible in which Shostakovich forged his mature style. The Second was seen as experimental, the Twelfth seemed merely excremental.” Perhaps Shostakovich intended the work to be a satire, in keeping with the satirical character of each of his symphonies, beginning with the Fifth. Excellent performances are conducted by Barshai in 1995, Vasily Petrenko in 2009, and Jansons in 2019.

Music commemorating revolution:

Music from revolutionary periods:

- Music of the American Revolution;

- Music of the Mexican Revolution;

- Music of the Soviet Revolution; Russian Civil War Songs;

- Music of the French Revolution;

- Music of the Irish Revolution; songs of Irish rebellion;

- Music of the Chinese Revolution;

- Music of the Cuban Revolution; and

- Music of the Greek War of Independence.

Other compositions:

- László Lajtha, Symphony No. 7, "Revolution," Op. 63 (1957) (approx. 31’): “Lajtha wrote the Revolution Symphony in response to the Hungarian uprising of 1956, mercilessly crushed by Russian and Warsaw Pact forces.”

Music: songs and other short pieces

- The Beatles, “Revolution” (lyrics)

- John Lennon, "Power to the People" (lyrics)

- The Rolling Stones, "Street Fighting Man" (lyrics)

- Blaise Siwula, Nicolas Letman-Burtinovic & Jon Panikkar, “Insurrection”

- Sérgio Assad, Clarice Assad & Third Coast Percussion, “The Rebel”

Visual Arts

- Marc Chagall, The Revolution (1937)

- José Clemente Orozco, Zapatista's Marching (1931)

- Eugene Delacroix, The Liberty Leading the People (1930)

- Diego Rivera, The Perpetual Renewal of the Revolutionary Struggle (1926)

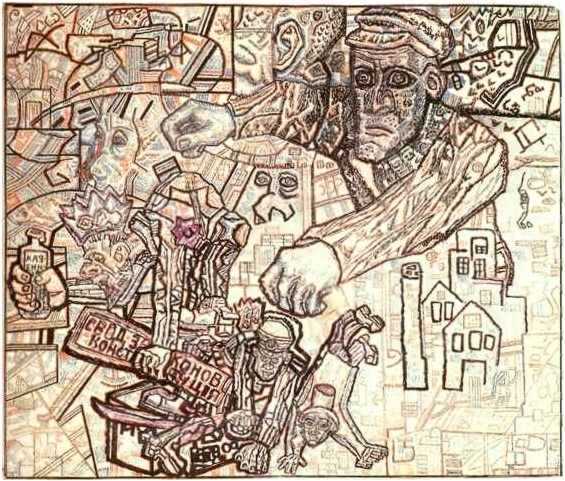

- Pavel Filonov, Formula of the Revolution (1925)

- Boris Kostudiev, February 27 (1917)

- David Burliuk, Revolution (1917)

Film and Stage

- Battleship Potemkin, a silent film portraying in microcosm the Russian revolution of 1905

- For many Russians, Alexander Nevsky represents resistance against a German invasion.

- Spartacus: a revolt of slaves in the Roman Empire

- Bloody Sunday, “the re-creation of the 1972 outbreak of violence during a pro-I.R.A. civil-rights march in Londonderry, Northern Ireland”

- If . . .: British boarding school students revolt in this 1960s counter-culture film

- Viva Zapata! About the Mexican revolutionary hero

- Chicken Run, about standing up for yourself and others, so you’re not all used as ingredients for chicken pies