We do not know everything. Awareness of this fact is an important first step in the intellectual domain.

- The psychic task which a person can and must set for himself, is not to feel secure, but to be able to tolerate insecurity, without panic and undue fear. [Erich Fromm]

- Ignorance more frequently begets confidence than does knowledge: it is those who know little, not those who know much, who so positively assert that this or that problem will never be solved by science. [Charles Darwin, The Descent of Man (1871), Introduction.]

- Religion is so frequently a source of confusion in political life, and so frequently dangerous to democracy, precisely because it introduces absolutes into the realm of relative values. [Reinhold Niebuhr]

- Education is a progressive discovery of our own ignorance. [Will Durant]

- Life is “doubt in action” . . . [Stephen Burn, reviewing Joseph McElroy’s Night Soul and Other Stories.]

- The wise man is cautious and shuns evil; the fool is reckless and sure of himself. [The Bible, Proverbs 14:16]

- When you know a thing, to recognize that you know it, and when you do not know a thing, to recognize that you do not know it. That is knowledge. [Confucius, The Analects, 2:17.]

- Ignorance is like a delicate exotic fruit: Touch it, and the bloom is gone. [Oscar Wilde, “The Importance of Being Earnest,” Act 1.]

- I do not know what I appear to the world; but to myself I seem to have been only a boy playing on the seashore, and diverting myself in now and then finding a smoother pebble or a prettier shell than ordinary, whilst the great ocean of truth lay all undiscovered before me. [Isaac Newton]

We religious Humanists and scientific naturalists celebrate something most people shun; skepticism and doubt, the ability to entertain and even invite uncertainty. We recognize that by cultivating and practicing these intellectual qualities, we equip ourselves to learn and grow. They are among the hallmarks, and tools, of intellectual humility.

As with the muscles of our bodies, these virtues probably never develop unless we exercise them. Still, they are not characterizing features of our lives but reminders of our human limitations and our unwavering commitment to learn, not merely to insist that we know.

The yearning for a sense of certainty cuts deep within us. In our evolutionary past, when one bit of hesitation could make the difference between surviving the attack of a predator and being eaten alive, the inclination to “jump to conclusions” may have conveyed an evolutionary advantage. We no longer live in that environment today but in an environment and social milieu that is friendlier to thoughtful consideration. Moreover, our contribution to the social framework depends on this latter attribute. We owe many of our greatest advances to people who doubted, questioned, and eventually overturned what was commonly assumed or held to be inalterably true.

The desire to know is at the root of nearly every human advance in science, literature, technology, the arts, sports and perhaps every important human endeavor. Without it, we might well have remained cave-dwellers lacking even the knowledge to build a fire to cook our food.

Yet the human being wants not merely to know, but to be certain – to feel that he knows. That craving leads not only to knowledge, but also to its opposite, an entrenched ignorance that glorifies and perpetuates itself. Like Lady Bracknell’s model of ignorance who never touches the prickly spines on the tree of knowledge, the one who knows all has settled in to a life of self-satisfied if not entirely blissful ignorance. “Inquiring minds want to know” was the slogan of a popular but tawdry tabloid that spoon-fed tawdry misinformation to the public under the guise of knowledge and inquiry.

Few things, if anything at all, will aggravate true believers more than an invitation to doubt: such people see an inconvenient fact or an inescapable conclusion of logic not as an opportunity to grow, but as a threat to a “truth” on which they have already settled. A mature and responsible mind comes to recognize avoidance of facts and reason as a sign that its views merit reconsideration and change, but the mind that is absolutely convinced of its own infallibility treats facts, logic and reason as tools to be used to support presently held opinions and ignored for every other purpose.

“Intellectual humility involves acknowledging the limitations of one’s knowledge and that one’s beliefs might be incorrect.” Research “findings are suggestive of dual psychological pathways to intellectual humility; either cognitive flexibility or intelligence are sufficient for high intellectual humility, but neither is necessary.”

Doubt and skepticism are key components of a genuine intellectual humility. Without them we cannot learn, or grow intellectually. In a sense, skepticism is a theory of knowledge.

Though one cannot spend a healthy lifetime merely doubting, the wise never fear to doubt. They know that the truth will not only survive their doubt, but be strengthened in its crucible, and that new truths will emerge from it.

Science recognizes that all its truths are provisional, subject to change as additional information comes to light. “In science, being skeptical does not mean doubting the validity of everything, nor does it mean being cynical. Rather, to be skeptical is to judge the validity of a claim based on objective empirical evidence.”

In the field of religion, too, doubt is an important and often overlooked tool, for although the Truth of our experience is our own personal Truth revealed from within, what we make of our Truth is a function of our growth and our ability to interpret the meaning of our experience in the context of all our relationships.

In our model, then, we see doubt and skepticism not as threats to our sense of security, and certainly not as characterizing attitudes, but as invitations to become more and better than we are. We seek to use intellectual humility as a reminder that gaining knowledge requires us to conform our understanding to What Is, instead of expecting What Is to conform to our understanding. In the language of traditional religion, this is nothing less than the distinction between obeying God and declaring oneself to be God. How odd it is, and how tragic, that so much of our culture takes the latter path while claiming to worship in the former.

Today we celebrate the virtue of intellectual humility: the affirmative power of doubt and skepticism to bring knowledge where ignorance now dwells or once dwelt. We bow to the reality around and within us, and resolve to approach it humbly and respectfully, recognizing our fallibility and the limits of our knowledge even as we seek to know more.

Real

True Narratives

Having been told that the soul was without form, she was much perplexed at David's words, "He leadeth my soul." "Has it feet? Can it walk? Is it blind?" she asked; for in her mind the idea of being led was associated with blindness. Of all the subjects which perplex and trouble Helen, none distresses her so much as the knowledge of the existence of evil, and of the suffering which results from it. For a long time it was possible to keep this knowledge from her; and it will always be comparatively easy to prevent her from coming in personal contact with vice and wickedness. The fact that sin exists, and that great misery results from it, dawned gradually upon her mind as she understood more and more clearly the lives and experiences of those around her. The necessity of laws and penalties had to be explained to her. She found it very hard to reconcile the presence of evil in the world with the idea of God which had been presented to her mind. One day she asked. "Does God take care of us all the time?" She was answered in the affirmative. "Then why did He let little sister fall this morning, and hurt her head so badly?" Another time she was asking about the power and goodness of God. She had been told of a terrible storm at sea, in which several lives were lost, and she asked, "Why did not God save the people if He can do all things?" [Annie Sullivan, Letters, March 22, 1888.]

True narratives on skepticism and intellectual humility:

- Jennifer Michael Hecht, Doubt: A History: The Great Doubters and Their Legacy of Innovation from Socrates and Jesus to Thomas Jefferson and Emily Dickinson (Harper One, 2003).

- Keith DeRose and Ted A Warfield, Eds., Skepticism: A Contemporary Reader (Oxford University Press, 1999).

- Richard H. Popkin, The History of Skepticism: From Savonarola to Bayle (Oxford University Press, 2003).

- Richard H. Popkin, Skepticism: An Anthology (Prometheus Books, 2007).

- Steven Gimbel, Einstein’s Jewish Science: Physics at the Intersection of Politics and Religion (The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2012): how Einstein’s complex physics threatened the Nazis, who insisted on a black-and-white worldview of everything. See also Hans Reichenbach, (Steven Gimbel and Anke Walz, eds.) Defending Einstein: Hans Reichenbach’s Writings on Space, Time and Motion (Cambridge University Press, 2006).

- Joshua Zeitz, Lincoln’s God: How Faith Transformed a President and a Nation (Viking, 2023): “As a young man, Lincoln was barely a Christian in the conventional sense. He was skeptical of the Bible’s miracles, read freethinkers like Thomas Paine and may even have been the author of a tract attacking religion.”

- Adam Shatz, The Rebel’s Clinic: The Revolutionary Lives of Frantz Fanon (Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2024): “He was both a militant and a doctor, someone who promoted a 'belief in violence' while also practicing a 'commitment to healing.' An acquaintance recalls being struck by Fanon’s compassion: 'He treated the torturers by day and the tortured at night.'”

- Adam Phillips, On Giving Up (Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2024): “. . . the prolific British psychoanalyst Adam Phillips promotes curiosity, improvisation and conflict as antidotes to the deadening effects of absolute certainty.”

Technical and Analytical Readings

- John Greco, Ed., The Oxford Handbook of Skepticism (Oxford University Press, 2008).

- Charles Landesman, Skepticism: The Central Issues (Wiley-Blackwell, 2002).

- J.L. Schellenberg, The Wisdom to Doubt: A Justification for Religious Skepticism (Cornell University Press, 2007).

- Megan Stielstra, The Wrong Way to Save Your Life: Essays (Harper Perennial, 2017): “. . . a life-enriching collection of essays by a conscientious writer and teacher who knows that asking the right questions is more important than having all the answers”.

- Zadie Smith, Changing My Mind: Occasional Essays (Penguin Press, 2009): “. . . ambivalence, doubt and confusion are essential to forming dynamic new hybrid selves. . .”

- Adam Grant, Think Again: The Power of Knowing What You Don’t Know (Viking, 2021): in arguing for “confident humility”, Grant argues that “we can simultaneously be confident in our ability to uncover the truth while acknowledging we may be wrong at present. We must convey our uncertainties and information gaps to others, he argues.”

- Alec Wilkinson, A Divine Language: Learning, Algebra, Geometry and Calculus at the Edge of Old Age (Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2022): “. . . what Wilkinson achieves by the end isn’t so much a command over mathematics as some humility toward it — a willingness to accept it, despite his frustrations, in a kind of détente. . . . The world seems bigger to him than it once did. He can sense new melodies, even if he doesn’t know all the words.”

- Walter Sinnott-Armstrong, Moral Skepticisms (Oxford University Press, 2006).

- Shelly Kagan, Answering Moral Skepticism (Oxford University Press, 2023).

- Stanley Cavell, The Claim of Reason: Wittgenstein, Skepticism, Morality, and Tragedy (Oxford University Press, 1979), “challenges our conception of what philosophy is (or of what philosophy in its American academic tradition has come to be), our understanding of skepticism in the history of philosophy, the significance of Wittgenstein 's Philosophical Investigations, and the meaning of the relationship between literature and philosophy.”

- P. F. Strawson, Skepticism and Naturalism: Some Varieties (Columbia University Press, 1985).

- Gilles Motet & Corinne Bieder, eds., The Illusion of Risk Control: What Does it Take to Live With Uncertainty? (Springer, 2020).

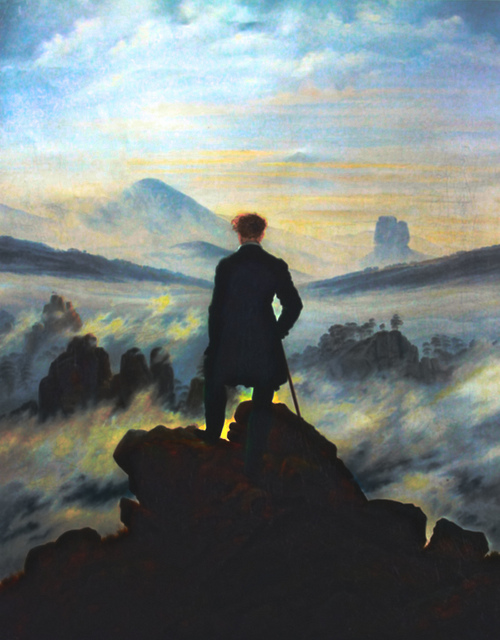

Photographs

Documentary and Educational Films

Imaginary

Fictional Narratives

Among all these glowing hearts and thoroughly convinced minds, there was one sceptic. How came he there? By juxtaposition. This sceptic's name was Grantaire, and he was in the habit of signing himself with this rebus: R. Grantaire was a man who took good care not to believe in anything. Moreover, he was one of the students who had learned the most during their course at Paris; he knew that the best coffee was to be had at the Café Lemblin, and the best billiards at the Café Voltaire, that good cakes and lasses were to be found at the Ermitage, on the Boulevard du Maine, spatchcocked chickens at Mother Sauget's, excellent matelotes at the Barrière de la Cunette, and a certain thin white wine at the Barrière du Compat. He knew the best place for everything; in addition, boxing and foot-fencing and some dances; and he was a thorough single-stick player. He was a tremendous drinker to boot. He was inordinately homely: the prettiest boot-stitcher of that day, Irma Boissy, enraged with his homeliness, pronounced sentence on him as follows: "Grantaire is impossible"; but Grantaire's fatuity was not to be disconcerted. He stared tenderly and fixedly at all women, with the air of saying to them all: "If I only chose!" and of trying to make his comrades believe that he was in general demand. All those words: rights of the people, rights of man, the social contract, the French Revolution, the Republic, democracy, humanity, civilization, religion, progress, came very near to signifying nothing whatever to Grantaire. He smiled at them. Scepticism, that caries of the intelligence, had not left him a single whole idea. He lived with irony. This was his axiom: "There is but one certainty, my full glass." He sneered at all devotion in all parties, the father as well as the brother, Robespierre junior as well as Loizerolles. "They are greatly in advance to be dead," he exclaimed. He said of the crucifix: "There is a gibbet which has been a success." A rover, a gambler, a libertine, often drunk, he displeased these young dreamers by humming incessantly: "J'aimons les filles, et j'aimons le bon vin." Air: Vive Henri IV. [Victor Hugo, Les Misérables (1862), Volume III – Marius; Book Fourth – The Friends of the A B C, Chapter I, “A Group Which Barely Missed Becoming Historic”.]

"Looking at these stars suddenly dwarfed my own troubles and all the gravities of terrestrial life. I thought of their unfathomable distance, and the slow inevitable drift of their movements out of the unknown past, into the unknown future. I thought of the great precessional cycle that the pole of the earth describes. Only forty times had that silent revolution occurred during all the years that I had traversed. And during these few revolutions all the activity, all the traditions, the complex organizations, the nations, languages, literatures, aspirations, even the mere memory of Man as I knew him, had been swept out of existence. . .” [H.G. Wells, “The Time Machine” (1895).]

Novels and stories:

- Joseph McElroy, Night Soul and Other Stories (Dalkey Archive Press, 2011): “Reading “Night Soul” — a collection of 12 clever and oblique short stories — is, in fact, a little like being a member of Marlow’s audience in “Heart of Darkness.” We listen in a foggy void, and try to puzzle out the significance of a narrator’s inconclusive experiences.”

- Katie Kitamura, A Separation: A Novel (Riverhead Books, 2018): “. . . one detects an overriding fatalism about the possibility of human connection, a sense that ‘wife and husband and marriage are only words that conceal much more unstable realities, more turbulent than perhaps can be contained in a handful of syllables, or any amount of writing.’ It is this radical disbelief — a disbelief, it appears, even in the power of art — that makes Kitamura’s accomplished novel such a coolly unsettling work.”

- John Darnielle, Devil House: A Novel (MCD / Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2022): “I had no idea where it was going, in the best possible sense.”

- Cormac McCarthy, The Passenger: A Novel (Knopf, 2022): “. . . a pair of siblings contend with the world’s enigmas and their own demons.”

- Jan Jemc, Empty Theatre: A Novel, or The Lives of King Ludwig II of Bavaria and Empress Sisi of Austria (Queen of Hungary), Cousins, in Their Pursuit of Connection and Beauty Despite the Expectations Placed on Them Because of the Exceptional Good Fortune of Their Status as Beloved National Figures. . . (MCD, 2023): the central theme is skepticism about royalty.

- Dinaw Mengestu, Someone Like Us: A Novel (Knopf, 2024): “. . . we can’t rely on the well-timed reveal, the moment when all is made clear, nor enjoy knowing more than the characters while waiting for them to catch up. To appreciate Mengestu’s work, you have to be ready to live in uncertainty, to find any truths obliquely, if at all. If you can accomplish that, the journey is well worth the discomfort.”

- Jamie Quatro, Two-Step Devil: A Novel (Grove Press, 2024): “Thematically, the novel takes on numerous dichotomies: good versus evil, optimism versus realism, punishment versus redemption, God’s will versus free will. Yet rather than pitting these seeming polarities against each other, Quatro skillfully mines the gray areas between them, the realms of ambiguity that are far more indicative of the human experience.”

Poetry

It seems inconsistent with all human reason,

That God in his infinite goodness and love___

His wisdom, his power and mercy unending,

Would quietly sit in his mansion above,

While over the earth dire misfortune is pending,

Dissension and discord are rife thru the land,

Injustice prevails, and the innocent suffer,

And fairest and loveliest, fall at Death's hand.

Could he calmly sit, high on his throne in the sky

While pain and distress to his children drew nigh?

["A Skeptic's Thought," Colfax Burgoyne Harman]

If you should rise from Nowhere up to Somewhere,

From being No one to being Someone,

Be sure to keep repeating to yourself

You owe it to an arbitrary god

Whose mercy to you rather than to others

Won=t bear too critical examination.

Stay unassuming. If for lack of license

To wear the uniform of who you are,

You should be tempted to make up for it

In a subordinating look or tone,

Beware of coming too much to the surface

And using for apparel what was meant

To be the curtain of the inmost soul.

[Robert Frost, "The Fear of God".]

Music: Composers, artists, and major works

Dmitri Shostakovich, Symphony No. 15 in A Major, Op. 141 (1971) (approx. 41-47’) (recordings): “This final Shostakovich Symphony, written in a little over a month during the summer of 1971 as the composer faced declining health, is filled with persistent and unsettling ambiguity.” “By this time in his life, already an ill man, Shostakovich's compositional concerns took a turn inward. The questions the 15th asks are some of the most profound Shostakovich ever posed: about the limits of musical expression, about what musical individuality and personality might be, and about the apparent impossibility of creating symphonic coherence in the late 20th century. Every bar of the piece demands a variation on the same simple but utterly profound question: what does it all mean?” The ambiguity is on at least two levels. “After Stalin’s death in 1953 the pressure was relaxed, it’s true, but old habits were deeply ingrained. Shostakovich remained as enigmatic as ever. When he seems playful, is he in fact mocking himself or us? When he seems downcast, is it for real?” Shostakovich may have had his last laugh on us. Top performances are conducted by Maxim Shostakovich in 1972, Haitink in 1979, Kurt Sanderling in 1996, Jansons in 1996, Kondrashin in 2009, Gergiev in 2013, Vasily Petrenko in 2015, and Nelsons in 2021.

Charles Ives, The Unanswered Question (1908) (approx. 6-7’) (recordings): “The solo trumpet asks ‘The Question’ for the first time (out of seven), using half and quarter tones. There is an emphasis on the minor third interval within the trumpet part. The Question is also incredibly isolated from the string part, which is rather pertinent within the work. Each time the trumpet asks the question, it becomes more rhythmically displaced, louder and more agitated in tone. The ‘answerers’ are the woodwinds, who play chromatic motifs, which become more and more animated.” “There are several ways of interpreting the question and its response . . . The trumpet may be asking ‘The Perennial Question of Existence,’ as Ives wrote. The woodwinds may be saying, ‘I don’t know!’ with increasing impatience. Or maybe, as Ives suggests they begin to realize the futility of the question and start to mock it. The strings represent an eternal and unchanging reality. In the end, the question remains. It’s stated one final time by the trumpet as the strings’ G major chord fades into eternity.”

As Gustav Mahler approached death, he wrote an adagio movement for a tenth symphony (1910) (approx. 24-27’) (recordings). It was the only part of the symphony he completed. Somewhat like Ives’ shorter work, it begins as with an existential question. Mahler could not resist paying homage to the love of his life, his wife Alma, but minor chords permeate the love melody. The love theme returns, only to be engulfed again by existential doubt as the two motifs struggle for dominance. In contrast with Mahler's Ninth Symphony, which evokes many of the same themes, Mahler's sadness so engulfs him that he seems disoriented, an idea reinforced by a mini-scherzo. Existential angst continues, interspersed with occasional notes of playfulness but these too are tinged with sadness and doubt, as though Mahler was asking "why must I die?"; or “why has she abandoned me?” A hint of serenity gives way to a burst of noisy energy, as the hero continues to struggle internally. Alma returns to soothe him but soon the minor key of doubt creeps back. Never one for a brief good-bye, Mahler continues in this vein throughout the remainder of this tragically incomplete work. Perhaps Mahler’s marital difficulties explain the work’s genesis, and why he did not complete it. “In 1910, other fears were coming true for Mahler. His wife Alma had had an affair with the architect Walter Gropius, who mistakenly sent a letter intended for Alma to ‘Herr Direktor Mahler.’ The letter, in which Gropius begged Alma to leave her husband, precipitated a marital crisis . . . Mahler covered the pages of its manuscript with tortured outcries – ‘Madness, seize me, the accursed! Negate me, so I forget that I exist, that I may cease to be!’, or ‘To live for you! To die for you!’, and even the dedication of the love song at the heart of the Symphony’s finale to his wife, using an affectionate form of her name, 'Almschi!'” In this work, Mahler continues to struggle with life and meaning, as he had in his Symphony No. 9, only now he also faces losing the love of his life. Bernstein in 1991, Rattle in 2000 (this link contains Deryk Cooke’s completion of the symphony), Tilson Thomas in 2008, Gielen in 2010, and Boulez in 2010, have conducted excellent performances.

Anton Webern‘s music is practically a study in ambiguity, extending Schoenberg’s twelve-tone system. “Webern is best known for breaking with tonality and for creating serial composition. His innovations were formative in the musical technique which later became known as total serialism.” His music “is typified by very spartan textures, in which every note can be clearly heard; carefully chosen timbres, often resulting in very detailed instructions to the performers and use of extended instrumental techniques (flutter tonguing, col legno, and so on); wide-ranging melodic lines, often with leaps greater than an octave; and brevity . . .” “After his death, young composers of the Darmstadt circle recognized Webern’s work as groundbreaking for their integral serialism.” For most listeners, however, his music remains not mysterious a mystery. Here is a playlist of his works.

Other works:

- Ida Gotkovsky, Symphonie Brillante, for wind orchestra (1989) (approx. 20’) is an extended musical question. From the program notes for band: “In the first movement, Arioso lento, unison clarinets present long, sustained phrases which are repeated later by other soloists. The contrasting Prestissimo con brio features repetitive woodwinds and percussion challenged by exploding brasses which lead to a brilliant symphony finale.”

- Philip Glass, Symphony No. 2 in C Minor (1994) (approx. 43’): here, Glass expands on the polytonality of Milhaud and Honegger but also focuses on “the ambiguity this sort of language creates.” [Donald Felsenfeld, from the notes for this album]

- Benjamin Frankel, Symphony No. 5, Op. 46 (1967) (approx. 19’), reflects 20th century anxiety and doubt; yet, “. . . tonality, melody and serialism can not only coexist happily but actually work together to very positive ends.”

- Alban Berg, 3 Orchesterstücke (3 Pieces for Orchestra), Op. 6 (1914-1915, rev. 1929) (approx. 20’) (recordings): “Berg’s effort constantly strives beyond the already exaggerated extremes of musical expression and gesture that so strongly characterize Schoenberg’s Five Pieces. No other work of Berg’s shows such a feverish complexity of texture; no other printed score of his contains such a density of expression marks or changes of tempo . . .”

- Daniel Asia, String Quartet No. 2 (1985) (approx. 27’) “is in four contrasting movements, with much of it about a theme and its variations. Like the earlier string quartet, it mixes the ghostly and nightmarish with the serene and peaceful, as it pushes to the fullest the emotional and physical range of the string quartet.”

- Thomas Wilson, Introit (Towards the Light) (1982) (approx. 23’): though the work’s title suggests a primal or existential quest, the music suggests uncertainty and caution.

- Jordan Dykstra, “Fathom Peaks Unseen” (2016) (approx. 11’) the title and the music evoke unseen peaks, unfathomed (not understood).

- Anna Thorvaldsdottir, Enigma (2019) (approx. 27-28’): “. . . imagine you’re suspended in some primordial gas cloud where matter is transforming, regenerating, building toward the birth of a planet . . .”

Albums:

- The Moody Blues, “Days of Future Passed” (1967) (41’). Band member John Lodge says: “The blues is about your life — how you live where you live. So we just adapted that whole sort of notion into writing our own songs about who we were in England . . . I know (the music) is a long way from the Delta, but it really was about us — about our thoughts and our dreams, about what had happened to us and what may happen to us in the future.”

- Taylor Ho Bynum 9-tette, “The Ambiguity Manifesto” (2019) (71’), “features three compositions that each receive two different examinations by the cornetist’s 9-tette, along with one additional piece. Of course, this is not a case of master and alternate takes. The group refracts the original guidelines that Bynum . . . has composed, coming up with something vastly different each time.”

- Matthew Shipp Trio, “The Unidentifiable” (2020) (55’): “The bulky chords are filled with color, timely disquieted by the loud, percussive outbursts that emerge from the far left reaches of Shipp’s keyboard. It’s a thrilling, occasionally spooky ride, and yet the tune’s main rhythmic idea suggests nu-jazz vibes and a taste of Latin.”

- Tony Malaby’s Sabino, “The Cave of the Winds” (2022) (52’): “Malaby has always been skilled at alternating elongated melodies and intense raspy wails.”

- Ivo Perelman, Chad Fowler, Reggie Workman & Andrew Cyrille, “Embracing the Unknown” (2024) (68’): “One of the strengths of the recording is that there is plenty of space for reflection and circumspection; the musicians' confidence allows them to develop their ideas patiently and deliberately, and the album's generous hour-plus runtime is well-served in that regard.”

Compositions from the dark side:

- Louis Théodore Gouvy, Le Giaour (The Non-Believer) Overture (approx. 13’) was “inspired by Byron’s poem and the painting by Delacroix”. Byron’s poem is a tale of romantic love and betrayal, a tale told visually by Delacroix.

Music: songs and other short pieces

- Iris Dement, “Let the Mystery Be” (lyrics)

Visual Arts

- Salvador Dali, The Endless Enigma (1938)

- Salvador Dali, Agnostic Symbol (1932)

- Wassily Kandinsky, In Grey (1919)

Awareness of place: a perspective on humility and another

Film and Stage

- Doubt: sexual predation within the Roman Catholic church provides the backdrop for this multi-layered exploration of doubt in an increasingly complex and ambiguous world.

- The Last Temptation of Christ: what if things are not as they seem to be?

- A Serious Man: the uncertainties of life as dark humor