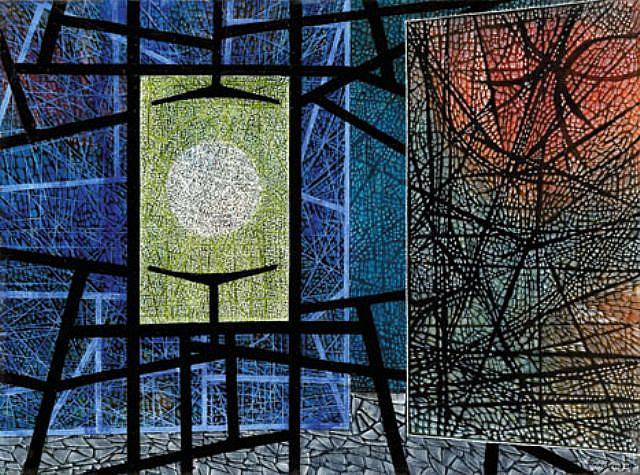

Numbers are symbols. Every building plan is a symbolic representation. At another level, there are abstract and realistic forms of art – fundamentally, both are abstract.

- Artists have a unique ability to paint the world, and to help people see injustice. They do it not with guns, but with pens and guitars and paintbrushes. [Teresa R. Funke, “Bursts of Brilliance for a Creative Life” blog.]

- The bulk of the world’s knowledge is an imaginary construction. History is but a mode of imagining, of making us see civilizations that no longer appear upon the earth. Some of the most significant discoveries in modern science owe their origin to the imagination of men who had neither accurate knowledge nor exact instruments to demonstrate their beliefs. If astronomy had not kept always in advance of the telescope, no one would ever have thought a telescope worth making. What great invention has not existed in the inventor’s mind long before he gave it tangible shape? [Helen Keller, The World I Live In (1907), Chapter VIII, “The Five-Sensed World.”]

- If you want a symbolic gesture, don’t burn the flag; wash it. [attributed to Norman Thomas]

Unlike any other species, human beings can design and build cities, devise complex financial and computer systems, and send objects and living beings into space. We can imagine entire universes, multiple universes and universes within universes; Big Bangs and sub-microscopic “strings”; and gods of every manner and description.

We can imagine things that have never been and bring them into being. Our unmatched capacity to think symbolically and reason abstractly has transformed the imagination into a powerful tool of invention, allowing us to create new technologies and the complex political, financial and economic systems we know today.

We can also imagine things that have never been and never could be. For example, picture yourself outside your home. With a running start, can you jump from that location just outside your home to the middle of San Francisco’s Golden Gate Bridge? Of course not but you can imagine it. In fact, if you are like most people, you cannot help imaging it if someone describes it to you. A great challenge of the human condition, especially in this age of advanced technologies and social, economic and political systems, is to inject a healthy grounding of reality into human endeavors without stifling the imaginative powers that spawn progress.

Language is not the only manifestation of abstract thinking but it is central to it. Scholarly literature on linguistic intelligence is summarized below.

In a popular children’s or party game, people pass on information, each person whispering to the next person, who then passes information on to the next. By the time “the information” reaches the end of the line, invariably, it has been completely transformed.

In some communities, words are confused with the res – the thing they represent. In his South Park series, self-described atheist Seth McFarlane took a jab at American atheism with a few episodes in which atheists had taken over the world. Instead of bringing about a utopia – since divisive religion had been eliminated – factions of atheists had the world at war because they could not agree on what to call themselves.

Language is not the only manifestation of abstract thinking but it is central to it. Scholarly literature on linguistic intelligence is summarized below.

In a popular children’s or party game, people pass on information, each person whispering to the next person, who then passes information on to the next. By the time “the information” reaches the end of the line, invariably, it has been completely transformed.

In some communities, words are confused with the res – the thing they represent. In his South Park series, self-described atheist Seth McFarlane took a jab at American atheism with a few episodes in which atheists had taken over the world. Instead of bringing about a utopia – since divisive religion had been eliminated – factions of atheists had the world at war because they could not agree on what to call themselves.

Language is a medium of communication. Because it relies on the construction and communication of symbols, which must then be translated by the receiver, it is inherently imperfect. Each of may know what we mean by a word or phrase but the speaker’s or writer’s meaning may not be what the listener understands. In addition, the writer/speaker may have only a vague idea what she means by a word or phrase. We develop language in a social context, which shapes meaning and simultaneously limits it. As science is an attempt to approximate reality, language is an attempt to approximate meaning. Approximation, with its inherent inaccuracies, occurs both in the choice of words and in their communication. In addition, language evolves. Words may take on several meanings soon after they are introduced into a language. Then, over time, those meanings may evolve, because words – especially words that refer to human affairs, as opposed to a physical substance like water – represent abstractions with several elements. For example, the word “religion” can refer to a belief system, a system of practices, relationship to a community, a set of high ideals and many other things. Yet some groups of people – usually those at the extremes of religious ideology – absolutely insist that it means one thing, which invariably is what they mean by it. Such dogmatic literalism does not tend toward a productive outcome. Communication then becomes a turf war over the meaning for words. Linguistic intelligence necessarily includes an ability to understand what others mean by their use of language. For this reason and perhaps others, it is related to empathy.

Language imprecision and its effects have been the subject of several studies. When asked to label unfamiliar objects, participants tended to give rare objects longer labels than frequent objects. Some learning styles do not seem to suit people whose linguistic intelligence predominates over their other intelligence parameters. Girls are more likely to become engaged in science when science education is described as an activity (“let’s do science”) than when it is described as an identity (let’s be scientists).

Language can be a manipulative tool. In George Orwell’s 1984, the party controlled the culture by controlling the language (Newspeak), a strategy that has become eerily familiar in our age of radio, television and the internet. Marketers and politicians well know the effects of word choice. Willingness to participate in clinical research is in part a function of whether the research is described as a trial or a study. A proposition stated in the affirmative will likely be interpreted differently versus the same proposition stated in the negative.

Still, language is an essential part of life among sentient species, not only humans. Vocabulary is positively associated with reasoning ability in children. Language can be an adjunct to empathy, and to the tendency to remember to do things (prospective memory, vigilance and monitoring of future tasks). Empathic linguistic tools are important in clinical medical practice. “. . . higher verbal intelligence, reading ability, and executive functioning (abstract reasoning and cognitive flexibility) may be protective against criminal behavior” in maltreated children. One study revealed that ‘’language abilities rather than numerical skills are essential for quantifier comprehension”. People with relatively high verbal intelligence are more likely to persist in taking medications for more than two years, which may partly explain why they tend to live longer than people who do not. People with high verbal and non-verbal intelligence demonstrate a proclivity toward black humor.

Several factors are relevant to linguistic intelligence. Memory appears to play an important role. One study’s findings suggest: “Functional diversity of brain networks supports consciousness and verbal intelligence”. No surprise, reading enhances “vocabulary, general knowledge, and verbal skills”. “Both level of, and change in, language-based cognition during adolescence (are) associated with midlife vocabulary and language function, even after controlling for midlife occupation and education.” “. . . parental education exerts a modest shared environmental effect, explaining no more than 3 to 4% of the variation in verbal intelligence”. “Inherent auditory skills rather than formal music training shape the neural encoding of speech”. Integrating visual and linguistic information facilitates learning. Core language skill has been shown to be stable from infancy to adolescence, suggesting substantial biological foundations of verbal intelligence. Research on children with dyslexia suggests “a processing trade-off between visuospatial and phonological demands”. Idiom and the frequency of recognized word patterns have significant effects on comprehension. Maternal intake of certain drugs seems to enhance verbal intelligence in offspring. Verbal intelligence appears to be impaired by post-traumatic stress disorder and Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Excessive internet use raises concerns for the “development of brain structures and verbal intelligence”. Videogame play appears to delay development of microstructure in brain regions associated with verbal intelligence.

Physiologically, gray matter abnormalities in language processing areas of the brain have been shown to be related to verbal ability. Patterns of brain activity on fMRI during language processing are complex. Chorioamnionitis, a bacterial infection of the membranes surrounding the fetus, “might be a risk factor for performance and verbal intelligence quotient impairment and severe cognitive deficits” in preterm infants. “Alpha Band Resting-State EEG Connectivity Is Associated With Non-verbal Intelligence”. A “Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count” software program has been developed to assess effectiveness of narrative communication. Some genetic foundations of linguistic ability have been identified. Preserved verbal intelligence has been studied in relation to auditory processing disorders, encephalitis and other cerebral pathologies. Low verbal intelligence appears to play a role in attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder.

Real

True Narratives

We walked down the path to the well-house, attracted by the fragrance of the honeysuckle with which it was covered. Some one was drawing water and my teacher placed my hand under the spout. As the cool stream gushed over one hand she spelled into the other the word water, first slowly, then rapidly. I stood still, my whole attention fixed upon the motions of her fingers. Suddenly I felt a misty consciousness as of something forgotten--a thrill of returning thought; and somehow the mystery of language was revealed to me. I knew then that "w-a-t-e-r" meant the wonderful cool something that was flowing over my hand. That living word awakened my soul, gave it light, hope, joy, set it free! There were barriers still, it is true, but barriers that could in time be swept away. I left the well-house eager to learn. Everything had a name, and each name gave birth to a new thought. As we returned to the house every object which I touched seemed to quiver with life. That was because I saw everything with the strange, new sight that had come to me. On entering the door I remembered the doll I had broken. I felt my way to the hearth and picked up the pieces. I tried vainly to put them together. Then my eyes filled with tears; for I realized what I had done, and for the first time I felt repentance and sorrow. I learned a great many new words that day. I do not remember what they all were; but I do know that mother, father, sister, teacher were among them--words that were to make the world blossom for me, "like Aaron's rod, with flowers." It would have been difficult to find a happier child than I was as I lay in my crib at the close of that eventful day and lived over the joys it had brought me, and for the first time longed for a new day to come. [Helen Keller, The Story of My Life (1904), Part I, Chapter IV.]

At first, when my teacher told me about a new thing I asked very few questions. My ideas were vague, and my vocabulary was inadequate; but as my knowledge of things grew, and I learned more and more words, my field of inquiry broadened, and I would return again and again to the same subject, eager for further information. Sometimes a new word revived an image that some earlier experience had engraved on my brain. I remember the morning that I first asked the meaning of the word, "love." This was before I knew many words. I had found a few early violets in the garden and brought them to my teacher. She tried to kiss me: but at that time I did not like to have any one kiss me except my mother. Miss Sullivan put her arm gently round me and spelled into my hand, "I love Helen." "What is love?" I asked. She drew me closer to her and said, "It is here," pointing to my heart, whose beats I was conscious of for the first time. Her words puzzled me very much because I did not then understand anything unless I touched it. I smelt the violets in her hand and asked, half in words, half in signs, a question which meant, "Is love the sweetness of flowers?" "No," said my teacher. Again I thought. The warm sun was shining on us. "Is this not love?" I asked, pointing in the direction from which the heat came. "Is this not love?" It seemed to me that there could be nothing more beautiful than the sun, whose warmth makes all things grow. But Miss Sullivan shook her head, and I was greatly puzzled and disappointed. I thought it strange that my teacher could not show me love. A day or two afterward I was stringing beads of different sizes in symmetrical groups--two large beads, three small ones, and so on. I had made many mistakes, and Miss Sullivan had pointed them out again and again with gentle patience. Finally I noticed a very obvious error in the sequence and for an instant I concentrated my attention on the lesson and tried to think how I should have arranged the beads. Miss Sullivan touched my forehead and spelled with decided emphasis, "Think." In a flash I knew that the word was the name of the process that was going on in my head. This was my first conscious perception of an abstract idea. For a long time I was still--I was not thinking of the beads in my lap, but trying to find a meaning for "love" in the light of this new idea. The sun had been under a cloud all day, and there had been brief showers; but suddenly the sun broke forth in all its southern splendour. Again I asked my teacher, "Is this not love?"] [Helen Keller, The Story of My Life (1904), Part I, Chapter VI.]

Language grows out of life, out of its need and experiences. At first my little pupil's mind was all but vacant. She had been living in a world she could not realize. Language and knowledge are indissolubly connected; they are interdependent. Good work in language presupposes and depends on a real knowledge of things. As soon as Helen grasped the idea that everything had a name, and that by means of the manual alphabet these names could be transmitted from one to another, I proceeded to awaken her further interest in the objects whose names she learned to spell with such evident joy. I never taught language for the PURPOSE of teaching it; but invariably used language as a medium for the communication of thought; thus the learning of language was coincident with the acquisition of knowledge. In order to use language intelligently, one must have something to talk about, and having something to talk about is the result of having had experiences; no amount of language training will enable our little children to use language with ease and fluency unless they have something clearly in their minds which they wish to communicate, or unless we succeed in awakening in them a desire to know what is in the minds of others.

At first I did not attempt to confine my pupil to any system. I always tried to find out what interested her most, and made that the starting-point for the new lesson, whether it had any bearing on the lesson I had planned to teach or not. During the first two years of her intellectual life, I required Helen to write very little. In order to write one must have something to write about, and having something to write about requires some mental preparation. The memory must be stored with ideas and the mind must be enriched with knowledge before writing becomes a natural and pleasurable effort. Too often, I think, children are required to write before they have anything to say. Teach them to think and read and talk without self-repression, and they will write because they cannot help it.

Helen acquired language by practice and habit rather than by study of rules and definitions. Grammar with its puzzling army of classifications, nomenclatures, and paradigms, was wholly discarded in her education. She learned language by being brought in contact with the living language itself; she was made to deal with it in everyday conversation, and in her books, and to turn it over in a variety of ways until she was able to use it correctly. No doubt I talked much more with my fingers, and more constantly than I should have done with my mouth; for had she possessed the use of sight and hearing, she would have been less dependent on me for entertainment and instruction. [Annie Sullivan, Letters, March 22, 1888.]

On language:

- John McWhorter, Nine Nasty Words: English in the Gutter – Then, Now, and Forever (Avery, 2021): “. . . a deeply intelligent celebration of language that teaches us how to see English in high definition and love it as it really is, right now and in its myriad incarnations to come”.

- Akhil Reed Amar, The Words That Made Us: America’s Constitutional Conversation, 1760-1840 (Basic Books, 2021): “. . . his chief concern is words, and as the subtitle indicates, those words are less the text of the Constitution itself than the rich cacophony of expression — the national conversation — that produced that text.”

- Rosemary Salomone, The Rise of English: Global Politics and the Power of Language (Oxford University Press, 2021): “How the English Language Conquered the World”.

- Joshua Bennett, Spoken Word: A Cultural History (Knopf, 2023) is a book about Nuyoricans that “traces the roots, rise and influence of a movement that continues to reverberate.”

On virtual reality technology:

- Jaron Lanier, Dawn of the New Everything: Encounters With Reality and Virtual Reality (Henry Holt & Company, 2017): “Enter the holodeck.”

- Jeremy Bailenson, Experience On Demand: What Virtual Reality Is, How It Works, and What It Can Do (W.W. Norton & Company, 2018).

On how information technologies are transforming life:

- Xiaowei Wang, Blockchain Chicken Farm: And Other Stories of China’s Countryside (FSG Originals x Logic, 2020): “A blockchain is a type of software, most famously used to create Bitcoin, that can make nearly tamper-proof digital records. When customers buy the chicken, they don’t need to take Jiang’s word that his birds strolled around in the sunshine. They can trust the implacable math.”

Other narratives on abstract thinking:

- Robert Calasso, The Celestial Hunter (Farrar, Straus, & Giroux, 2020):: about humanity’s trasition from hunted to hunter.

- Jacob Goldstein, Money: The True Story of a Made-Up Thing (Hachette, 2020): “The Fiction That Makes the World Go Round”.

Visual imagery:

- Sandra Ristovska and Monroe Price, eds., Visual Imagery and Human Rights Practice (Palgrave MacMillan, 2018).

- Karen P. Kelly, Ph.D., The Power of Visual Imagery: A Reading Comprehension Program for Students with Reading Difficulties (Corwin, 2006).

- Patricia Bjaaland Welch, Chinese Art: A Guide to Motifs and Visual Imagery (Tuttle Publishing, 2008).

- Lyombi Eko, The Regulation of Sex-Themed Visual Imagery: From Clay Tablets to Tablet Computers (Palgrave MacMallin, 2015).

- James G. Harper, ed., The Turk and Islam in the Western Eye, 1450-1750: Visual Imagery before Orientalism (Routledge, 2011).

- Kathleen Nolan, Queens in Stone and Silver: The Creation of a Visual Imagery of Queenship in Capetian France (Palgrave MacMillan, 2009).

Technical and Analytical Readings

Book narratives:

- Terrence W. Deacon, The Symbolic Species: The Co-evolution of Language and the Brain (W. W. Norton & Co., 1997).

- Theresa Schilhab, Frererik Stjernfeldt and Terrence Deacon, eds., The Symbolic Species Evolved (Springer, 2012).

- Steven Pinker, The Language Instinct: How the Mind Creates Language (William Morrow & Co., 1994).

- Noam Chomsky, On Language: Chomsky’s Classic Works (New Press, 2007).

- Noam Chomsky, Language and Mind (Cambridge University Press, 2006).

- Frederik Stjernfelt, Diagrammatology: An Investigation on the Borderlines of Phenomenology, Ontology, and Semiotics (Springer, 2007).

- Daniel L. Everett, Language: The Cultural Tool (Pantheon Books, 2012): “Everett makes a case for language having arisen as a combination of three elements: ‘Cognition + Culture + Communication.’”

- David Shariatmadari, Don’t Believe a Word: The Surprising Truth About Language (Norton, 2019): “It’s a brisk and friendly introduction to linguistics, and a synthesis of the field’s recent discoveries.”

Photographs

Documentary and Educational Films

Imaginary

Fictional Narratives

. . . this sea of harmony is not a chaos; great and profound as it is, it has not lost its transparency; you behold the windings of each group of notes which escapes from the belfries. You can follow the dialogue, by turns grave and shrill, of the treble and the bass; you can see the octaves leap from one tower to another; you watch them spring forth, winged, light, and whistling, from the silver bell, to fall, broken and limping from the bell of wood; you admire in their midst the rich gamut which incessantly ascends and re-ascends the seven bells of Saint-Eustache; you see light and rapid notes running across it, executing three or four luminous zigzags, and vanishing like flashes of lightning. Yonder is the Abbey of Saint-Martin, a shrill, cracked singer; here the gruff and gloomy voice of the Bastille; at the other end, the great tower of the Louvre, with its bass. The royal chime of the palace scatters on all sides, and without relaxation, resplendent trills, upon which fall, at regular intervals, the heavy strokes from the belfry of Notre-Dame, which makes them sparkle like the anvil under the hammer. At intervals you behold the passage of sounds of all forms which come from the triple peal of Saint-Germain-des-Prés. Then, again, from time to time, this mass of sublime noises opens and gives passage to the beats of the Ave Maria, which bursts forth and sparkles like an aigrette of stars. Below, in the very depths of the concert, you confusedly distinguish the interior chanting of the churches, which exhales through the vibrating pores of their vaulted roofs. [Victor Hugo, Notre-Dame de Paris, or, The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1831), Volume I, Book Third, Chapter II, “A Bird’s-Eye View of Paris”.]

The generating idea, the word, was not only at the foundation of all these edifices, but also in the form. The temple of Solomon, for example, was not alone the binding of the holy book; it was the holy book itself. On each one of its concentric walls, the priests could read the word translated and manifested to the eye, and thus they followed its transformations from sanctuary to sanctuary, until they seized it in its last tabernacle, under its most concrete form, which still belonged to architecture: the arch. Thus the word was enclosed in an edifice, but its image was upon its envelope, like the human form on the coffin of a mummy. And not only the form of edifices, but the sites selected for them, revealed the thought which they represented, according as the symbol to be expressed was graceful or grave. Greece crowned her mountains with a temple harmonious to the eye; India disembowelled hers, to chisel therein those monstrous subterranean pagodas, borne up by gigantic rows of granite elephants. . . . . . . the human race has two books, two registers, two testaments: masonry and printing; the Bible of stone and the Bible of paper. No doubt, when one contemplates these two Bibles, laid so broadly open in the centuries, it is permissible to regret the visible majesty of the writing of granite, those gigantic alphabets formulated in colonnades, in pylons, in obelisks, those sorts of human mountains which cover the world and the past, from the pyramid to the bell tower, from Cheops to Strasbourg. The past must be reread upon these pages of marble. This book, written by architecture, must be admired and perused incessantly; but the grandeur of the edifice which printing erects in its turn must not be denied. That edifice is colossal. Some compiler of statistics has calculated, that if all the volumes which have issued from the press since Gutenberg’s day were to be piled one upon another, they would fill the space between the earth and the moon; but it is not that sort of grandeur of which we wished to speak. Nevertheless, when one tries to collect in one’s mind a comprehensive image of the total products of printing down to our own days, does not that total appear to us like an immense construction, resting upon the entire world, at which humanity toils without relaxation, and whose monstrous crest is lost in the profound mists of the future? It is the anthill of intelligence. It is the hive whither come all imaginations, those golden bees, with their honey. [Victor Hugo, Notre-Dame de Paris, or, The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1831), Volume I, Book Fifth, Chapter II, “This Will Kill That”.]

He read the general's signals. "Five and Four are to keep among the guns to the left and prevent any attempt to recover them. Seven and Eleven and Twelve, stick to the guns you have got; Seven, got into position to command the guns taken by Three. Then we're to do something else, are we? Six and One, quicken up to about ten miles an hour and walk round behind that camp to the levels near the river--we shall bag the whole crowd of them," interjected the young man. "Ah, here we are! Two and Three, Eight and Nine, Thirteen and Fourteen, space out to a thousand yards, wait for the word, and then go slowly to cover the advance of the cyclist infantry against any change of mounted troops. That's all right. But where's Ten? Halloa! Ten to repair and get movable as soon as possible. They've broken up Ten!" [H.G. Wells, “The Land Ironclads” (1905).]

Novels and stories:

- Aimee Bender, The Color Master: Stories (Doubleday, 2013): the author’s characters use colors and objects to understand our confusing world. We can well view this as a metaphor for language and symbolic thought in general.

- Richard McGuire, Here: A Graphic Novel (Pantheon Books, 2015): “. . . the comic-book equivalent of a scientific breakthrough. It is also a lovely evocation of the spirit of place, a family drama under the gaze of eternity and a ghost story in which all of us are enlisted to haunt and be haunted in turn.”

- Zadie Smith, Grand Union: Stories (Penguin, 2019): “For a lesser writer, we might wish more avidly for an editor to have stepped in to carve the book into something more specific, more pointed. But Smith’s stature will have made many of her readers completists and her artistic development a matter of interest.”

- César Aira, The Divorce: A Novel (New Directions, 2021): “Aira captures the texture of the world by flying away from it. Rather than a rejection of reality, his dreamlike sequences are an acknowledgment of it.”

- Yan Ge, Strange Beasts of China: A Novel (Melville House, 2021) “embraces cryptozoology’s ethos of self-delusion and adventure, staging the fictional Chinese city of Yong’an as a hub of evasive creatures simply called “beasts.” These live alongside humans in seemingly infinite arrangements, blending in yet leading distinct lives.”

- R.F. Kuang, Babel, or The Necessity of Violence: An Arcane History of the Oxford Translators’ Revolution (Harper Voyager, 2022), “is set in an alternate 19th century where the work of translation generates powerful, empire-fueling magic.”

- Natasha Brown, Universality: A Novel (Alfred A. Knopf Canada, 2025) “focuses on words: what we say, how we say it, and what we really mean. The follow-up novel to Natasha Brown’s Assembly is a compellingly nasty celebration of the spectacular force of language. It dares you to look away.” “. . . Brown deploys her skilful satire to tackle rhetoric itself, examining with nuanced precision the relationship between language, truth and power.”

Poetry

Poems:

- Wallace Stevens, “Not Ideas About the Thing but the Thing Itself”

- Walt Whitman, “A Song of the Rolling Earth”

Books of poetry:

- Jackie Wang, The Sunflower Cast a Spell To Save Us From the Void (Nightboat Books, 2021): “a symbolist dream diary for catastrophic times”.

Language:

Books of poetry on language:

- Douglas Kearny, Sho (Wave Books, 2021): “Navigating the complex penetrability of language, these poems are sonic in their espousal of Black vernacular strategies, while examining histories and current events through the lyric, brand new dances, and other performances.”

Music: Composers, artists, and major works

More than any other species, Homo sapiens thinks symbolically and abstractly. That is who we are.

All music is symbolic. The works presented below are among those in which the composer consciously sought to use the music to represent something else, such as art works and geometric forms. This leaves a wealth of musical symbolism for the other pages on this site.

In his Music Pictures, John Foulds explored this formally, suggesting a connection between music and painting.

- Music Pictures, Group II, for string quartet, “Aquarelles,” Op. 32 (1912) (approx. 13’) (here is an analysis)

- Music Pictures, Group III, for orchestra, Op. 33 (1912) (approx. 20’)

- Music Pictures, Group IV, Suite for String Orchestra, Op. 55 (1916) (approx. 11’)

- Music Pictures, Group VI, for piano, Op. 81, “Gaelic Melodies” (1924) (approx. 7-8’)

- Music Pictures, Group VII, for piano, Op. 13, “Landscapes” (1927) (approx. 6’)

Performer/composer Anthony Braxton represents his compositions with shapes and drawings, so that music – which is already an abstract expression of feelings, ideas, memories and the like – is represented in yet another form.

- Composition No. 1 (1968) (approx. 13’)

- Composition No. 6C (approx. 10’)

- Composition No. 6E (approx. 20’)

- Composition No. 6g (approx. 39’)

- Composition No. 23G (approx. 8’)

- Composition No. 23j (1976) (approx. 14’)

- Composition No. 34 (1976) (approx. 7’)

- Composition No. 45 (1978) (approx. 12’)

- Composition No. 55 (1978) (approx. 12’)

- Composition No. 95 (approx. 49’)

- Composition No. 165 (1992) (approx. 50’)

- Composition No. 211 (1997) (approx. 55’)

- Composition No. 247 (2000) (approx. 62’)

- Composition No. 255 (2003) (approx. 57’)

- Composition No. 402 (2017) (approx. 46’)

- Composition No. 408 (2017) (approx. 54’)

- Composition No. 409 (2017) (approx. 50’)

- Composition No. 410 (2017) (approx. 41’)

- Composition No. 411 (2017) (approx. 58’)

- Composition No. 412 (2017) (approx. 51’)

- Composition No. 414 (2017) (approx. 52’)

- Composition No. 415 (2017) (approx. 49’)

- Composition No. 416 (2017) (approx. 47’)

- Composition No. 418 (2017) (approx. 46’)

- Composition No. 419 (2017) (approx. 73’)

- Composition No. 420 (2017) (approx. 71’)

- Composition No. 429 (2021) (approx. 43’)

Other compositions:

- Larry Sitsky, Seven Meditations on Symbolist Art (1975) – drawn from paintings by seven symbolist artists

- Giorgio Federico Ghedini, Architetture (Architectures), Concerto for Orchestra (1940) (approx. 16-19’): the work signals its “organization of abstract musical elements into a series of edifices in sound, which are in their turn cemented together by a clear thematic and constructional logic”.

- Reza Vali, Calligraphy compositions (1989-2014) (approx. 99’) – in describing the works, the composer does not explain the relevance or significance of calligraphy.

- George Antheil, String Quartet No. 1 (1924) (approx. 16’): “It is very radical – and it will surprise and perhaps offend you by its desperate banality. But it is the banality of a Picasso, I hope, or a Matisse. It sounds exactly like a third-rate string orchestra in Budapest trying to harmonize kind of mongrel Hungarian . . . themes – but doing it with kind of a brilliant success.” [the composer, describing the work]

- Charles T. Griffes, Poem, for Flute and Orchestra, A. 93 (1919) (approx. 11’) is “. . . a one-movement flute concerto that suggests Claude Debussy’s Prelude to the Afternoon of a Faun as a reference point.”; performed as Poem for Flute and Piano (approx. 9’)

- Rued Langgaard, Symphony No. 6, “Det Himmelrevende” (The Heaven-Rending), BVN 165 (1919-1920, rev. 1928-1930) (approx. 20-22’) (list of recorded performances): “. . . by giving it the title ‘Det Himmelrivende’ (‘The Heaven-Rending’) he turned the music into something more expressly religious, a cosmic struggle between the forces of good and evil.”

- George Crumb, Metamorphoses (Book 1), Ten Fantasy Pieces (after celebrated paintings) for amplified piano (2015-2017) (approx. 37-42’)

- Crumb, Metamorphoses (Book 2), Ten Fantasy Pieces (after celebrated paintings) for amplified piano (2018-2020) (approx. 39’)

- Fred Frith, “Allegory” (2001) (approx. 15’)

- John Aylward, Celestial Forms and Stories (2021) (approx. 54’): “Three movements of the suite take their cue from figures in Ovid’s tales: the provident quartets ‘Mercury’ and ‘Daedalus,’ as well as the more opulent ‘Narcissus.’ Meanwhile, the more abstractly titled movements, ‘Ephemera’ and ‘Ananke,’ underscore that figurative content is not the only vector in Aylward’s musical engagement with Ovid’s Metamorphoses.”

- Elena Ruehr, O’Keefe Images (2013) (approx. 33’), after Georgia O’Keefe paintings

- Robert Schumann, Märchenbilder (Fairytale Pictures), Op. 113 (1851) (approx. 15-16’) (list of recorded performances) “consists of four movements, tonally centered around D.” Perhaps “the first two pieces are scenes from the story of Rapunzel, the third depicts Rumpelstiltskin dancing with fairies outside his house, and the last represents Sleeping Beauty.”

- Paul Dooley, Mondrian’s Studio (2022) (approx. 17’): “Dooley has used three snapshots from Mondrian’s career to provide a musical equivalent to each period.”

- Anna Clyne, Abstractions (2016) (approx. 17’) “is a suite of five movements inspired by five contrasting contemporary artworks from the Baltimore Museum of Art and from the private collection of Rheda Becker and Robert Meyerhoff, for whom this music honors.”

- Clyne, Color Field (2020) (approx. 15-18’) “was inspired by Mark Rothko’s Orange, Red, Yellow (1961) – a powerful example of the artist’s Color Field paintings, featuring red and yellow framing a massive swash of vibrant orange that seems to vibrate off the canvas.”

Albums in which the artists use music to represent visual works:

- George McMullen with Vinny Golia, “Line Drawings, Volume 1” (2020) (40’); and “Line Drawings, Volume 2” (2020) (32’): “All tracks are free improvised duets, capturing the instruments close up and beautifully recorded in a rather reverberant space.”

- Matthias Tschopp Quartet, “Matthias Tschopp Quartet plays Miró” (2013) (53’): each track portrays a painting by the Spanish artist Joan Miró.

- Harris Eisenstadt, “Woodblock Prints” (2010) (42’): “. . . the music is inspired by Japanese woodblock prints, as depicted on the cover, yet contrastingly, whereas the Japanese art is purposely created against empty space, the density and complexity of Eisenstadt's arrangements are high, with no space for silence, but that is easily compensated by the overall warmth coming from the horn section.”

- Jaap Blonk, Bart van der Patton & Pieter Mours, “Hugo Ball Six Sound Poems, 1916” (2021) (109’): “Ball’s sound poem is thoroughly grounded in historical sense and awareness; it is formulated as a response not to symbolism or to any other rival avant-garde […] but to the contemporary state of discourse under early twentieth-century capitalism.”

- Joe Lovano & Dave Douglas, “Sound Prints” (2018) (67’): “. . . the two embrace Shorter’s current quartet’s heralded spatial awareness, invigorating interplay and cross-conversational dialogue . . .”

- Matthew Shipp, “Symbol Systems” (1995) (61’): “The recording is the result of a day spent in the studio by Shipp effusing what Shipp described to writer Lyn Horton in All About Jazz as thirteen 'compact miniatures of ideas imposed on a structure.'”

- Ivo Perelman & Matthew Shipp, “Complementary Colors” (2016) (46’): “The ten improvisations, to which Perelman conjured a title post-production, play off of colors first separate 'Violet,' 'Yellow,' then together 'Violet And Yellow.'”

- Dan Flanagan, “The Bow & the Brush” (2023) (79’) is an album of 14 works for unaccompanied violin, after contemporary and historical artworks. “integrates the visual arts with new music.”

Other albums:

- MC Maguire, “Transmutation of Things” (2022) (50’): “Central to my current aesthetic, is taking Pop hits, de-constructing them, and then reassembling the data into massive, abstract canvases. The purpose of this is to use the original primal musicality as a talisman to enter a new, dream-like, mathematically proportioned world.”

- Mary Halvorson, “About Ghosts” (2025) (44’): “Between Halvorson’s writing and Amaryllis’ almost preternatural level of sensitivity in their interplay, they’ve become sharply attuned to painting lush and deeply floral sound-pictures.”

Music: songs and other short pieces

- Franz Schubert (composer), “An der Mond” (To the Moon), D. 193 (1815) (lyrics)

- Franz Schubert (composer), “An die Nachtigall” (To the Nightingale), D. 196 (1815) (lyrics)

Visual Arts

Film and Stage

- The Imitation Game dramatizes the true story of how Alan Turing and a few other brilliant people cracked the Nazi Enigma codes, enabling the Allied forces to disrupt Nazi military operations at key strategic points during World War II. Once Turing had cracked the code, he had to devise statistical models to prevent the Nazis from knowing that he had done it. This allowed Allied military forces to win the war strategically, even though they allowed many lives to be lost directly.