We need balance in life, and in how we see life. Balance is essential to a healthy and well-ordered life.

- It is the same with people as it is with riding a bike. Only when moving can one comfortably maintain one’s balance. [Albert Einstein]

- The delicate balance of mentoring someone is not creating them in your own image, but giving them the opportunity to create themselves. [attributed to Steven Spielberg]

- My journey has always been the balance between chaos and order. [attributed to Philippe Petit]

To gain another perspective on human values, and life, consider the issue of balance. Life is like riding a bicycle: if we lose our balance, then we fall off. The consequences can range from a scraped knee to utter calamity.

Balance implies a relationship, or set of relationships between and among the various elements and features in and of our lives. It can be dominated or influenced by context. Each aspect of balance will occupy its own space and time in our lives.

This chapter raises planes of analysis in addition to those explored in other chapters.

- Internal/cognitive (soul, spirit, meaning) versus external/active (reason, courage, Faith) versus mixed (motivation, purpose);

- Tangible versus symbolic: this plane is especially difficult to pin down, because all of our values are symbolic, but to the extent that they are expressed in action, they are relatively more tangible; on the other hand, technologies such as real-time MRI of the brain now allow us to see the tangible side of thoughts and feelings.

- Static versus dynamic, though a strong case can be made that all of our values are dynamic, both in their underlying internal character, and as we express them. On the other hand, people who are highly consistent in their values could be said to be relatively more static than those whose values, thoughts, feelings, and actions change more noticeably over time.

There are two kinds of balance: psychological balance and life balance.

Psychological balance

A leading work on psychological balance, which is “a dynamic state characterized by relatively stable characteristics that can adapt to change”, summarizes the matter: “There were statistically significant associations between Consistency (i.e., degree of integration of a universal value structure as self-related characteristics that motivate personal goals and behavior), Flexibility (i.e., degree of ability to re-define meaningful and important goals in response to situational challenge), and five well-being variables (e.g., Meaning in Life). Self/Others Ratio (i.e., ratio of motivation to serve self-interest and the interest of others), operationalized as a binary variable (e.g., close and away from 1), moderated some of these associations.” Psychological balance is internal, i.e., within self; it directly reflects how we see things. A psychological balance scale has been developed. As we venture into higher levels of ethical development, and into the creative forces, we see fewer and fewer counterpart values, probably because the values already incorporate both sides.

Consistency stands in contrast with inconsistency, i.e., a lack of integration, wholeness, or “agreement” within the self. Internal inconsistency disrupts balance. “At all levels of information processing in the brain, neural and cognitive structures tend towards a state of consistency. When two or more simultaneously active cognitive structures are logically inconsistent, arousal is increased, which activates processes with the expected consequence of increasing consistency and decreasing arousal. Increased arousal is experienced as aversive, while the expected or actual decrease in arousal as a result of increased consistency is experienced as rewarding. Modes of resolution of inconsistency can be divided into purely cognitive solutions, such as changing an attitude or an associated motor plan, and behavioural solutions, such as exploration, aggression, fear, and feeding.” Seen broadly enough and within a framework centered on intrinsic worth, consistency is an unalloyed good. However, if any element of mental values processing is unhealthy, then inconsistency will arise: the nature and extent of the damage that it will inflict is a function of what is off balance. Seen more narrowly, this might be described as an unhealthy consistency, but that would reflect an incomplete view of consistency.

Flexibility can never be an unalloyed good. There is such a thing as being too flexible, such as being so open-minded that your brains fall out, or compromising with evil in such a way that it is encouraged and empowered. Chamberlain’s appeasement of Hitler is a case in point. Moral flexibility can always be assessed in comparison with and in contrast to scrupulousness. Whether we can ethically compromise our scruples depends on how broad a view we take of them, and how relatively absolute they are. This is the central problem of the lifeboat dilemma: under what circumstances should an innocent person’s life be sacrificed? The main challenges for most people are to see the matter broadly enough (1) to recognize that any course of action or inaction will affect everyone on the lifeboat, and (2) to see the consequences of decisions broadly enough so that they honor everyone’s intrinsic worth, not only the person who by outward appearances is most directly and most profoundly affected. In every dynamic of flexibility-scrupulousness, an outward manifestation is always present. We can also consider and address flexibility in several additional ways, all of which can be considered in the flexible-scrupulous dynamic:

- Ideals versus practicality: Ideals relate to a desired state of affairs, usually one that does not (yet) exist. Practicality is a strategy for tempering our ideals, of necessity, to consider the overarching reality that is greater than the moral actor-protagonist. Practicality is useful when it helps us advance our ideals. An example is the Bernie Sanders Presidential candidacy in the United States. Sanders’ supporters argued that voters should not compromise their ideals. However, many people whose hearts were with Sanders did not support his election: they recognized that he was not likely to win, and that even if he did win, his Presidency would compromise their and his long-term ideals. Bernie Sanders could not have gotten his legislative proposals enacted without Congressional support. Most of his major proposals did not have enough support to win enactment. Meanwhile, voters tend to blame the party of the sitting President when they think that the country is on the wrong track. Therefore, the most likely outcome of a Sanders presidency would have been the loss of Congressional power in the midterm elections, with potentially disastrous consequences for the Sanders movement. (Think of how Jimmy Carter tried to take on big oil and other monied interests, lost those battles, and came to be seen as a weak President; and how the election of Ronald Reagan followed, with long-term consequences inimical to Carter’s ideals, such as treating the fossil fuel issue as the moral equivalent of war.) This illustrates the point that political movements must be built from the ground up, and will fail if they are not. An exception is dictatorships, but even there, loss of support will eventually cause the regime to collapse. However, there is evidence that Sanders’ candidacy advanced his ideals, but only because he did not win. How is this different from Chamberlain’s appeasement of Hitler: Hitler might have been stopped with a united Europe but given the political realities in the United States during Carter’s presidency, there was no realistic chance of stopping big oil in the ways that Carter wanted to do. People wanted cheap oil, and were not inclined to think first about their grandchildren. The rise of the far right in the United States can well be analyzed as a matter of which side saw the practical realities more clearly; both sides had their ideals, though many people would not call a desire for power and control and ideal (it is, because it pertains to what people on the far right conceive of as a desirable state of affairs). The balance between ideals and practicality is complicated and tricky.

- Taking risks versus being cautious: Life presents us with choices between taking risks and being cautious, routinely, or we could say constantly. A risk may be external (e.g., taking out a loan to open a business) or internal (e.g., the emotional investment someone makes in a romantic relationship, which can be independent of and vastly different from the external actions associated with that investment). It may be a large risk or a small one. Sometimes, caution is the greater risk, such as when a person decides not to undergo surgery; however, that decision is cautious only as it relates to the risks of surgery, not as it relates to treatment for cancer. Sometimes, as in the example of cancer surgery, action can be more cautious than inaction.

- Being stable/constant versus changing (displaying dynamism): We are constantly faced with choices to remain the same or change. A change can be internal, such as changing one’s mind; or external, such as divorcing a spouse. However, people who change their minds are likely to change their actions too; and people who file for divorce churn inside before, during, and after the filing. People assess how well their situation and strategies suit them, and decide to change or not based on the issues involved, their life consequences (including the attendant risks that come with each course of action), issues of space (should someone run for board of education, or for President of the United States?) and time (is changing jobs worth it, when someone has only one year left until retirement?)

Meaning: What constitutes a healthy balance in someone’s life is a function of the meaning that person attaches to the various elements in life. A professional musician may be balanced in spending three hours per day practicing. Probably this would be an excessive amount of time for a high school band member with no musical aspirations beyond the high school band. Most professional musicians probably would consider eight hours of practice per day to be excessive but if a musician continued to improve by practicing for that long, then eight hours of practice per day could reflect a healthy balance, especially if the musician enjoyed it. After all, people routinely work for eight hours or more per day.

One person might consider devoting attention to a spouse for three hours per day to reflect an excellent life balance. Another person might be revulsed by that, seeing it as reflecting unhealthy dependence. Neither of them is necessarily right or wrong but the difference between two romantic partners in the meaning they attach to their relationship can be a troubling and in some cases a relationship-ending matter of contention. They do not want the same – or we might say compatible – balances in their lives.

A foodie might spend eight hours every day in the kitchen. If the time is spent cooking, that might reflect a balanced life, but if the foodie spends eight hours a day eating, that would reflect a life that is seriously out of balance – not because of the activity itself but because of the adverse effects of habitual overeating.

Young people incur hundreds of thousands of dollars in debt to obtain an advanced education. For some of them, the investment might be worth it; others may regret having made it.

How much time is someone best advised to spend exercising on an average day? How much time should be devoted to sleeping? How much time is a person best advised to spend on social media, or playing video games, if any? The answers will depend on where these activities fit into each person’s life, and the meaning they bring forth.

Life balance

“Balance in life . . . is defined as a state reflecting satisfaction or fulfillment in several important domains with little or no negative affect in other domains. Achieving balance in life allows people to satisfy the full spectrum of human development needs, both basic and growth needs, which in turn contributes to long-term happiness.” In contrast with psychological balance, life balance is comparatively external, i.e., it extends outside self to the material aspects of life. Like psychological balance, it too reflects how we see things but is not confined to that. A balanced life consists of several components, including the following.

- Of all the balance-in-life issues, work/life balance (WLB) is the most extensively considered. WLB can be defined operationally as “(t)he individual’s perception that work and non-work activities are compatible and promote growth in accordance with an individual’s current life priorities.” Perhaps a better definition is that WLB refers to a balance that is in fact healthy, not merely that the individual perceives it that way. There are other definitions and considerations. At least one scholarly paper identifies work/family balance and work/health balance, though those are contained within WLB. “Work-life balance is crucial for individuals to manage their professional responsibilities alongside personal commitments.” “. . . low work–life balance (WLB) can be harmful to health.” Workers with healthy WLB are more productive. Telecommunications offer an opportunity for individuals to change, and society to transform WLB.

- Work/play is a work-life issue but is presented as a separate category only because play is commonly seen as a distinction from work.

- Activity/rest: Part II of this book is devoted entirely to active values. Chapter 5 of Part IV is devoted to restoration. When we think of values, we think mainly of the values described in Part II, but we spend much of our time restoring ourselves, including the time we spend sleeping.

- Restoring/depleting: we spend much of our time exhausting ourselves. We work, study, exercise, and pursue goals. Restoration, which includes resting, relaxing, sleeping, and playing, offers a necessary antidote to that. This is another approach to the distinction between being active and resting.

- Being resolute/Accepting: We may be resolute about many things, and express it by persevering, being determined, being motivated and driven, and in many other ways. Still, we need space to accept, and to surrender to the things we cannot change.

- Serious/light-hearted: This dimension is mainly internal, more than with the other dimensions.

Real

True Narratives

With China's emergence as an economic power, the United States is newly concerned about the balance of economic and military power.

- Robert D. Kaplan, Monsoon: The Indian Ocean and the Future of American Power (Random House, 2010).

- Toshi Yoshihara and James R. Holmes, Red Star Over the Pacific: China's Rise and the Challenge to U.S. Maritime Strategy (Naval Institute Press, 2010).

- Bernard D. Cole, Great Wall at Sea: China's Navy Enters the Twenty-First Century (Naval Institute Press, 2010).

- Richard D. Fraser, Jr., China's Military Modernization: Building for Regional and Global Reach (Praeger, 2008).

Some people's idea of balance may be other people's idea of ridiculous. Commonly, propagandists promote an ideal in direct contravention to its expression.

- Nicholas O'Shaughnessy, Marketing the Third Reich (Routledge, 2018).

- Federico Finchelstein, A Brief History of Fascist Lies (University of California Press, 2022).

- Alex Carey, Taking the Risk Out of Democracy: Corporate Propaganda versus Freedom and Liberty (The University of Illinois Press, 1996).

- Joseph Minton Amann and Tom Breuer, Fair and Balanced, My Ass!: An Unbridled Look at the Bizarre Reality of Fox News (Nation Books, 2007).

- Peter Hart, The Oh Really Factor: Unspinning Fox News Channel's Bill O'Reilly (Seven Stories Press, 2003).

- Al Franken, Lies and the Lying Liars Who Tell Them: A Fair and Balanced Look at the Right (Dutton/Penguin, 2003).

- John Dean, Conservatives Without Conscience (Viking Adult, 2006).

- Will Bunch, Tear Down This Myth: How the Reagan Legacy Has Distorted Our Politics and Haunts Our Future (Free Press, 2010).

- Deborah R. Jaramillo, Ugly War, Pretty Package: How CNN and Fox News Made the Invasion of Iraq High Concept (Indiana University Press, 2009).

- Eric Boehlert, Lapdogs: How the Press Lay Down for the Bush White House (Free Press, 2006).

- Andrew Marantz, Anti-Social: Online Extremists, Techno-Utopians, and the Hijacking of the American Conversation (Viking, 2019): “‘Antisocial’ is about ‘web-savvy bigots,’ ‘soft-brained conspiracists’ and ‘mere grifters or opportunists,’ but it’s also about Marantz’s searching attempt to understand people he describes as truly deplorable without letting his moral compass get wrecked.”

Having seen how well propaganda worked in the United States, despite the nation’s historic wealth, oligarchs became more extreme:

- Yochai Benkler, Robert Faris & Hal Roberts, Network Propaganda: Manipulation, Disinformation, and Radicalization in American Politics (Oxford University Press, 2018).

- Amanda Carpenter, Gaslighting America: Why We Love It When Trump Lies to Us (Broadside Books, 2018).

- Cailin O'Connor & James Owen Weatherall, The Misinformation Age: How False Beliefs Spread (Yale University Press, 2018).

- Nathan Crick, ed., The Rhetoric of Fascism (University of Alabama Press, 2022).

- Grant Hamming & Natalie E. Phillips, Interrogating the Visual Culture of Trumpism (Routledge, 2024).

- David L. Swartz, The Academic Trumpists: Radicals Against Liberal Diversity (Routledge, 2025).

- The Washington Post Fact Checker Staff, Donald Trump and His Assault on Truth: The President's Falsehoods, Misleading Claims and Flat-Out Lies (Simon & Schuster, 2020).

- Lee McIntyre, Post-Truth (Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 2018).

Artificial economic bubbles are notorious for leading to calamity:

- William Quinn (Author), John D. Turner, Boom and Bust: A Global History of Financial Bubbles (Cambridge University Press, 2020).

- Hannah Catherine Davies, Transatlantic Speculations: Globalization and the Panics of 1873 (Columbia University Press, 2018).

- Phillip G. Payne, Crash!: How the Economic Boom and Bust of the 1920s Worked (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2015).

- Christopher Knowlton, Bubble in the Sun: The Florida Boom of the 1920s and How It Brought On the Great Depression (Simon & Schuster, 2020): “Many paid for their sins, largely through crippling alcoholism, personal bankruptcy and extreme public humiliation.”

- David Llewellyn-Smith & Ross Garnaut, The Great Crash of 2008 (Melbourne University Press, 2009).

- Adam Tooze, Crashed: How a Decade of Financial Crises Changed the World (Penguin Books, 2018).

- Paul Krugman, The Return of Depression Economics and the Crisis of 2008 (W.W. Norton and Company, 2008).

In the 1920s the United States lived under a Constitutional Amendment that banned alcoholic beverages. Spurred by "temperance societies," this episode in history, ironically, exemplifies intemperance.

- Daniel Okrent, Last Call: The Rise and Fall of Prohibition (Scribner, 2010).

- Garrett Peck, The Prohibition Hangover: Alcohol in America from Demon Rum to Cult Cabernet (Rutgers University Press, 2009).

From the dark side:

Greed:

- Justene Hill Edwards, Savings and Trust: The Rise and Betrayal of the Freedman’s Bank (W.W. Norton and Company, 2024): “Unbeknown to its depositors and supporters, however, the bank had quickly veered off course. A pot of uninvested funds proved irresistible to the well-connected white businessmen on the bank’s board of trustees, who began chipping away at the risk-limiting provisions in the charter.”

Technical and Analytical Readings

Photographs

Documentary and Educational Films

Imaginary

Fictional Narratives

In the meantime, while some sang, the rest talked together tumultuously all at once; it was no longer anything but noise. Tholomyès intervened. "Let us not talk at random nor too fast," he exclaimed. "Let us reflect, if we wish to be brilliant. Too much improvisation empties the mind in a stupid way. Running beer gathers no froth. No haste, gentlemen. Let us mingle majesty with the feast. Let us eat with meditation; let us make haste slowly. Let us not hurry. Consider the springtime; if it makes haste, it is done for; that is to say, it gets frozen. Excess of zeal ruins peach-trees and apricot-trees. Excess of zeal kills the grace and the mirth of good dinners. No zeal, gentlemen! [Victor Hugo, Les Misérables (1862), Volume I – Fantine; Book Third – In the Year 1817, Chapter VII, “The Wisdom of Tholomyés”.]

Tempering medieval justice:

Every city during the Middle Ages, and every city in France down to the time of Louis XII. had its places of asylum. These sanctuaries, in the midst of the deluge of penal and barbarous jurisdictions which inundated the city, were a species of islands which rose above the level of human justice. Every criminal who landed there was safe. There were in every suburb almost as many places of asylum as gallows. It was the abuse of impunity by the side of the abuse of punishment; two bad things which strove to correct each other. The palaces of the king, the hôtels of the princes, and especially churches, possessed the right of asylum. Sometimes a whole city which stood in need of being repeopled was temporarily created a place of refuge. Louis XI. made all Paris a refuge in 1467. [Victor Hugo, Notre-Dame de Paris, or, The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1831), Volume II, Book Ninth, Chapter II, “Hunchbacked, One Eyed, Lame”.]

Poetry

Loved a little, Worked a little…

Those were very fortunate people,

Who considered Love an obligation,

Or they just loved their task,

I remained busy all my life,

Loved a little, worked a little,

Sometimes love was a snag in the way of my work,

While sometimes duty didn’t allow me to love with passion,

Ultimately I got upset of the situation,

And left both my love and my work incomplete.

[Faiz Ahmed Faiz, “Loved a little, Worked a little”]

Two poems by John Milton express the value of balance:

From the dark side:

- Edgar Lee Masters, “Cooney Potter”

- Michael Rosen, “Chocolate Cake”

Music: Composers, artists, and major works

George Frideric Händel, L’Allegro, il Penseroso ed il Moderato (The Cheerful, the Thoughtful, and the Moderate Man), HWV 55 (1740) (approx. 100-140’) (libretto), is a pastoral ode studying two alternating moods, or tempers. “The texts of Parts I and II are based on the two delightful companion poems L'Allegro and Il Penseroso written in the previous century by the 22-year-old John Milton. The first of these poems depicts the joys of the active or extroverted life, the second the joys of the contemplative or introverted life.” “. . . the piece honors an Enlightenment aesthetic of balance and self-control that still resonates today.” Live recorded performances are by Gabrieli Consort (McCreesh); and Nicholas McGegan at Harvard in 2016. Excellent performances on disc are by Monteverdi Choir & English Baroque Soloists (Gardiner); Bach Choir & Ensemble Orchestral de Paris (Nelson) in 2000; Paul McCreesh & Gabrieli Players in 2015; Orchester der J.S. Bach-Stiftung (Lutz) in 2017; and Les Arts Florissants (Christie) in 2022.

Béla Bartók, Piano Concerto No. 2, Sz 95, BB 101 (1931) (approx. 28’): “The overall architecture of the work is intricately planned and reveals the composer’s characteristic fascination with symmetrical patterns.” Top performances are by Anda & Fricsay in 1959, Rudolf Serkin & Szell, Pollini & Abbado in 1979, Bronfman & Salonen in 1993, Andsnes & Boulez in 2004, Schiff & Iván Fischer in 1996, Bavouzet & Noseda in 2010, Wang & Rattle in concert in 2017, and Aimard & Salonen in 2023.

Jean-Yves Thibaudet is a classical pianist who has taken a balanced approach to music. “From the very start of his career, he has delighted in music beyond the standard repertoire, from jazz to opera, including works which he has transcribed himself for the piano.” He “has the rare ability to combine poetic musical sensibilities and dazzling technical prowess.” Thibaudet is known for “elegant and insightful musicality . . .” “Without exception, his interpretations are always inspiringly original yet remain in keeping with the composer's intended spirit . . .” Here is a link to his releases.

Conductor Pierre Monteux was known for his elegance, refinement and balance. “To some observers, his conducting semmed almost effortless. His beat was small. He never indulged in histrionics. And yet, when in front of an orchestra, his authority was absolute. The music unfolded with the utmost subtlety of nuance. One orchestral section was always transparent to another.” Here are links to his playlists and of him conducting live.

Though they were written early in the Romantic era, Robert Schumann’s piano trios are more nearly like those of the twentieth century than they are like their contemporaneous works. In addition, because of Schumann’s inner turbulence, they are on the gray-dark side of temperance and balance. Listen to the works also for the balance among the instrumentalists, which Schumann preserved. “Schumann’s trios, like his symphonies, gravitate toward the middle in sound and substance. Neither the piano nor the violin use much of their higher registers, and Schumann being Schumann, there is no superficial brilliance in any of the parts.”

- Piano Trio No. 1 in D Minor, Op. 63 (1847) (approx. 29-33’), is the most highly regarded of the three. “From the opening bars of Robert Schumann’s Piano Trio No. 1, we are swept into a drama filled with soaring passion and turbulence. . . . Schumann composed the D minor Piano Trio in a single burst of creative energy during the summer of 1847.” “In spite of (or precisely because of) the erstwhile angst, the music steadily builds to a glorious ending that, like other Schumann conclusions, may propel you to your feet with an energetic shout of glory. The composite work is a definitive study in bi-polarity, perhaps a personal reflection of Schumann's own soul.” Top recorded performances are by Cortot, Thibaud & Casals in 1928; Gilels, Kogan & Rostropovich in 1958; Previn, Chung & Tortelier in 1978; Borodin Trio in 1989; Florestan Trio in 1998; Nicholas Argerich, Capuçon & Capuçon in 2006; Andsnes, Tetzlaff & Tetzlaff in 2009; Vienna Piano Trio in 2010; Melnikov, Faust & Queyras in 2014; and Trio Karénine in 2015.

- Piano Trio No. 2 in F Major, Op. 80 (1847) (approx. 27-32’): “The opening movement of the F-major Trio is athletic and optimistic, with a feeling of jovial bigness. The descending theme introduced just before the contrapuntally dense development is an allusion to one of Schumann’s songs, and the main theme of the slow movement is a cousin to that song-theme. The third movement is not a scherzo, but a sort of barcarolle in 'moderate tempo' . . .” Top recorded performances are by Beaux Arts Trio in 1966, Andsnes, Tetzlaff & Tetzlaff in 2009, Trio Karénine in 2016, Kungsbacka Piano Trio in 2020, and Trio Wanderer in 2021.

- Piano Trio No. 3 in G Minor, Op. 110 (1851) (approx. 24-28’): “The G-minor Trio explores darker, more passionate territory.” “Schumann the reader, the writer and the storyteller was also the great composer of character pieces, little tableaux like illustrated pages in a book with narrative suggestions and recurring dramatis personae. . . . The trio is sometimes criticized for its haphazardness and repetition yet it is studded with jewels and suffused with a personality that is so recognizably and purely Schumann's.” Top recorded performances are by Beaux Arts Trio in 1972, Borodin Trio in 1990, Andsnes, Tetzlaff & Tetzlaff in 2009, Benvenue Fortepiano Trio in 2010, and Horszowski Trio in 2019.

Johann Sebastian Bach, Cantata No. 211 in G Major, “Schweigt stille, plaudert nicht - Kaffeekantate” (Be Still, Stop Chattering, or Coffee Cantata), BWV 211 (1734) (approx. 26-29’) (lyrics), “. . . is essentially a miniature comic opera that tells the story of a disgruntled father, Schlendrian, who argues with his caffeine-obsessed daughter . . .”

“Counterpoint is the relationship between two or more melody lines that are played at the same time. These melodies are dependent on each other to create good-sounding harmonies, but also are independent in rhythm and contour.” “Counterpoint is a musical style of composition that employs more than one voice; however, rather than having a melody line and a harmony line, each voice is equally important in the composition and carries part of the melody. Counterpoint is a form of polyphony that creates a dialogue between the treble clef and the bass clef, and each contributes something meaningful to a joint conversation instead of one serving a supporting role to the other.” “Good counterpoint requires two qualities: (1) a meaningful or harmonious relationship between the lines (a ‘vertical’ consideration—i.e., dealing with harmony) and (2) some degree of independence or individuality within the lines themselves (a ‘horizontal’ consideration, dealing with melody).” Several Renaissance composers notably developed this style.

- Vicente Lusitano, Motets: “Vicente Lusitano’s name is familiar to specialists of the Renaissance as a key witness to the practice of improvised counterpoint . . .”

- Josquin des Prez, Motets and Chansons

- Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina, choral music

- Alexander Agricola, “A Secret Labyrinth” album

- Jacob Obrecht, Missa de Sancta Donatiano; Missa Sub Tuum Praesidium; Missa Maria Zart

- Heinrich Isaac, “Choralis Constantinus 1508” album

- Adrian Willaert, “Adriaan Willaert and Italy” album; Missa Christus resurgens

- Cipriano de Rore, Il quinto libro di Madrigali (1568)

- Orlando di Lasso (Orlande de Lassus), Psalmi Davidis Pœnitentiales; motets and chansons

- Carlo Gesualdo, Música sacra a 5 voces

- Ludwig Daser, “Polyphonic Masses” (2023) (56’), album by Huelgas Ensemble with Paul Van Nevel

Two minimalists have highlighted the idea of symmetry:

- Morton Feldman, Crippled Symmetry (1983) (approx. 78-94’): “Feldman was fascinated by the designs in Turkish rugs. Their symmetry was never quite perfect; in other words, it was crippled. Feldman realized this concept in musical terms.”

- John Adams, Fearful Symmetries (1988) (approx. 26-28’): “The music is, as its title suggests, almost maddeningly symmetrical.”

To my ears, twentieth century piano trios outside the lingering tradition of French romanticism do not convey as clear a sense of attentive listening as do their nineteenth century counterparts; they seem distracted by the concerns of their era. Still, they strike a scrupulous balance between the three instruments.

- Josef Suk, Piano Trio in C minor, Op. 2 (1891) (approx. 15-17’)

- Vitĕzslav Novák, Piano Trio quasi una balata in D minor, Op. 27 (1902) (approx. 16-17’)

- Anton Arensky, Piano Trio No. 1 in D Minor, Op. 32 (1894) (approx. 30-32’)

- Arensky, Piano Trio No. 2 in E Minor, Op. 67 (1905) (approx. 27’)

- Dmitri Shostakovich, Piano Trio No. 1 in C Minor, Op. 8, “Poème” (1923) (approx. 12’)

- Mieczysław Weinberg, Piano Trio, Op. 24 (1945) (approx. 30’)

- Lera Auerbach, Piano Trio No. 1, Op. 28 (1996) (approx. 12’)

Other works:

- Pierre-Octave Ferroud, Serenade (1927) (approx. 9’)

- Benjamin Frankel, Symphony No. 8, Op. 53 (1971) (approx. 26’)

- Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Il Sogno di Scipione (Scipio's Dream), K126 (1771) (approx. 83-108’) (libretto): Scipio must choose between wealth and stability, personified by Fortuna and Costanza.

- Walter Douglas Munn, piano music: Munn “was a mathematician (with a Ph.D. from Cambridge University) by profession, but also an accomplished pianist, and judging by the evidence on this CD, a composer with a good ear and a keen sense of balance and structure.”

- Alban Berg, String Quartet, Op. 3 (1910) (approx. 21-22’), “was probably the first extended composition consistently based on symmetrical pitch relations.”

- In Richard Strauss’ opera Daphne, Op. 82 (1937) (approx 94-114’) (libretto), a young woman is obsessed with nature, to the exclusion of everything else. Here is a more recent recording.

LPT is a ten-piece Afro-Cuban salsa band whose style could best be described as one of controlled energy. Though their rhythms drive forward consistently, they always remain controlled and balanced. Their albums include: “Se Quema el Mundo” (2021) (45’) and “Sin Parar” (2020) (40’).

Albums:

- Liquid Mind III, “Balance” (1999) (57’)

- Third Coast Percussion, “Unknown Symmetry” (2013) (78’)

- David Preston, Kit Downes, Kevin Glasgow & Sebastian Rochford, “Purple/Black (Vol. 2)” (2024) (41’): the tracks “hold the line” in a low-key straight-ahead jazz style.

From the dark side:

- Ivo Perelman, Matthew Shipp & Joe Hertenstein, “Scalene” (2017) (50’)

- Alarm Will Sound, “A/Rhythmia” (2009) (55’)

- Binker & Moses, “Feeding the Machine” (2022) (50’) presents images of a dystopian, out-of-balance world.

Compositions from the dark side:

- Missy Mazzoli, Dark with Excessive Bright (2018) (approx. 13-14’); Dark with Excessive Bright for violin and string quintet (2021) (approx. 14’): the title drawn from Dante’s Inferno, this work highlights the opposite of moderation. “The concerto riffs on baroque formulas while recycling motifs in fresh disguises. Like a photographer, Mazzoli captures moments rich in texture and charged with expression. They are hard to describe, but you can see them in your ear.”

Music: songs and other short pieces

- The Beatles, “Slow Down” (lyrics)

- The Band, “The Weight” (lyrics)

- Franz Schubert (composer), Genügsamkeit (A Feeling of Sufficiency), D. 143 (1815) (lyrics)

Visual Arts

- Jasper Johns, Target with Four Faces (1955)

- M.C. Escher, Symmetry Watercolor, 55 Fish

- M.C. Escher, Symmetry Watercolor 70 Butterfly

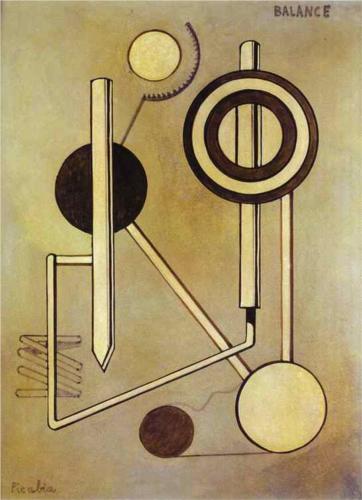

- Wassily Kandinsky, Balancement (1925)

- Giotto, Temperance (1302-05)

- Paul Klee, Portrait of Mrs. P in the South (1924) (notice the hat size)

- Nicolas Poussin, Helios and Phaeton with Saturn and the Four Seasons (ca. 1635) (Phaeton’s aspirations were beyond his reach)

- Nicolas Poussin, Midas and Bacchus (1629-30) (Bacchus grants Midas’ wish that all he touches turns to gold – which is inedible)

Film and Stage

- Chocolat, about the importance of keeping things on an even keel

- What’s Eating Gilbert Grape: a story of a young man whose sense of family responsibilities leaves him no room for himself

- The Pillow Book, this offbeat film that goes out of its way to challenge the viewer “is best watched as a richly sensual stylistic exercise filled with audaciously beautiful imagery, captivating symmetries and brilliantly facile tricks.”

- Coco: the underlying message here is about the balance between personal ambition and family obligation.