We do not enter a supernatural world when we transcend a previous limitation; it merely feels that way, because we have not experienced it before.

- Within ourselves, there are voices that provide us with all the answers that we need to heal our deepest wounds, to transcend our limitations, to overcome our obstacles or challenges, and to see where our soul is longing to go. [Debbie Ford]

- As pessimistic as I am about the nature of human beings and our capacity for atrocity and malevolence and betrayal and laziness and inertia, and all those things, I think we can transcend all that and set things straight. [Jordan Peterson]

- One can never consent to creep when one feels an impulse to soar. [Helen Keller]

- It is, after all, the responsibility of the expert to operate the familiar and that of the leader to transcend it. [Henry Kissinger]

Herein is a model based on a Humanistic view of scientific naturalism. Here, transcendence refers not to claims of other-worldliness but to transcending previous limitations, either our own or the limitations of what people previously thought possible. For example, a person may transcend her previous limitations by making a breakthrough in some area of personal development, that is, by doing something that she had never done before and perhaps did not think she could do. On a larger scale, Einstein transcended the previous limits of physics with his theory or general relativity.

Breaking through a previous limitation may feel as though we have entered another world. Perhaps this is what Paul Kurtz had in mind with his book title The Transcendental Temptation. Dr. Kurtz’s critique of the other-worldly and the paranormal is well taken but his exclusive focus on a literalist understanding of transcendental experiences is not. Transcendental experiences are useful, liberating, enlightening and spiritual, if interpreted for what they are: human experiences that seem as though we have been transported to another world. All that is necessary is that we remain in touch with reality as we enjoy the ride that the experience affords us.

There are many kinds of transcendence. We might transcend previous levels of personal performance, as in “personal best”, or previous levels of performance by anyone, as Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau arguably did as an art singer. An Einstein might take science into a new realm, transcending Newton’s linear physics, and transforming the science into the physics of relativity. A figure skater might master a quadruple jump, transcending previous limits of three rotations. These are entirely secular kinds of transcendence, not at all the kinds of supernatural transcendence that Paul Kurtz excoriated in The Transcendental Temptation.

Human progress in every field consists of one transcendent step, or leap, after another. This chapter addresses transcendence in human values. This refers to expressions (verbs) of personal qualities (nouns) that transcend norms.

- In our relations to other people, those qualities include agape, wisdom, and courage.

- In our relations to the material/conceptual world, those qualities include avidity, genius, and dedication.

Real

True Narratives

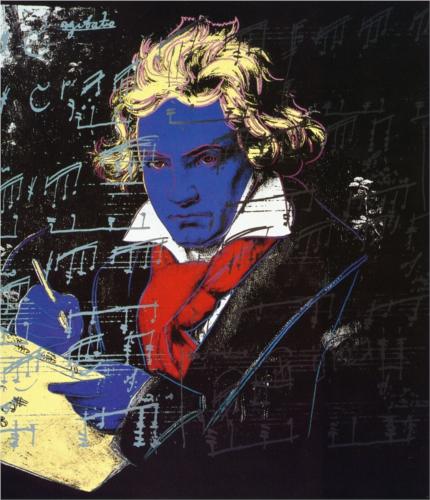

Ludwig van Beethoven transcended the art of musical composition. To do it, he had to transcend his deafness and the emotional torments of his youth.

- Elliott Forbes, ed., Thayer's Life of Beethoven, Part 1, (Princeton University Press, revised edition, 1991).

- Elliott Forbes, ed., Thayer's Life of Beethoven, Part 2, (Princeton University Press, revised edition, 1967).

- François Martin Mai, Diagnosing Genius: The Life and Death of Beethoven (McGill-Queens University Press, 2007).

- Alfred Christlieb Kalischer, ed., Beethoven's Letters: Volume 1; Volume 2 (1926).

Breaking social and political barriers:

- Martha S. Jones, Vanguard: How Black Women Broke Barriers, Won the Vote, and Insisted on Equality for All (Basic Books, 2020): “. . . an elegant and expansive history of Black women who sought to build political power where they could.”

Technical and Analytical Readings

Photographs

Documentary and Educational Films

Imaginary

Fictional Narratives

Novels:

- Laila Lalami, The Moor’s Account: A Novel (Pantheon Books, 2014): “Lalami sees the story as a form of moral and spiritual instruction that can lead to transcendence: 'Maybe if our experiences, in all of their glorious, magnificent colors, were somehow added up, they would lead us to the blinding light of the truth.' And 'the only thing at once more precious and more fragile than a true story,' she reminds us, 'is a free life.'”

- Yaa Gyasi, Transcendent Kingdom: A Novel (Knopf, 2020): “The transcendent kingdom of this Ghanaian, Southern, American novel is finally not a Christian or a scientific one, but the one that two women create by surviving a hostile environment, and maintaining their primal connection to each other.”

Poetry

I think continually of those who were truly great.

Who, from the womb, remembered the soul’s history

Through corridors of light, where the hours are suns,

Endless and singing. Whose lovely ambition

Was that their lips, still touched with fire,

Should tell of the Spirit, clothed from head to foot in song.

And who hoarded from the Spring branches

The desires falling across their bodies like blossoms.

What is precious, is never to forget

The essential delight of the blood drawn from ageless springs

Breaking through rocks in worlds before our earth.

Never to deny its pleasure in the morning simple light

Nor its grave evening demand for love.

Never to allow gradually the traffic to smother

With noise and fog, the flowering of the spirit.

Near the snow, near the sun, in the highest fields,

See how these names are fêted by the waving grass

And by the streamers of white cloud

And whispers of wind in the listening sky.

The names of those who in their lives fought for life,

Who wore at their hearts the fire’s centre.

Born of the sun, they travelled a short while toward the sun

And left the vivid air signed with their honour.

[Stephen Spender, “I Think Continually of Those Who Were Truly Great”]

Music: Composers, artists, and major works

Nicolò Paganini was among the greatest violinists of any age. His six violin concerti demand a level of technical proficiency that transcends what music had been before him. “For Paganini’s contemporaries, there was almost something miraculous about his playing. His music was unlike anything anyone had heard before—so difficult, so extravagant that no one else could play it.”

- Concerto for Violin and Orchestra No. 1 in D Major, Op. 6, MS. 21 (1815) (approx. 35-45’) (list of recorded performances): “Those who heard it were absolutely blown away – not just by the technical feats and showmanship Paganini had demanded of the instrument, but by the fact that he was actually able to play every single note. And these weren’t just notes: there were giant leaps, packed with all sorts of complex musical wizardry, the like of which no one had ever heard before.”

- Concerto for Violin and Orchestra No. 2 in B minor, Op. 7, MS. 48, “La Campanella” (1815) (approx. 27-33’) (list of recorded performances), is “renowned for its intricate and technically demanding solo passages and for the bell-like effects featured in both the solo and orchestral parts. The movement derives its nickname from those bell-like sounds, which evoke the imagery of the Italian folk song—also known as 'La campanella' . . .”

- Concerto for Violin and Orchestra No. 3 in E Major, MS. 50 (1826) (approx. 31-37’) (list of recorded performances): “Paganini wanted to dazzle his audience, but he also wanted to move them.”

- Concerto for Violin and Orchestra No. 4 in D minor, Op. 60 (1826) (approx. 31-36’) (list of recorded performances): fellow composer Louis Spohr wrote, “he is a complete wizard, and brings tones from his violin which were never heard before from that instrument.”

- Concerto for Violin and Orchestra No. 5 in A minor, MS. 78 (1829) (approx. 40-41’) (list of recorded performances), is “all of those things that the Romantic era is: opulent, showy, festive, a bit (or a lot) over-the-top music, with innovation, envelope-pushing, and a sumptuous musicality to enjoy.”

- Concerto for Violin and Orchestra No. 6 in E minor, MS. 75, Op. Posth. (1830) (approx. 38-41’) (list of recorded performances)

Similarly, Paganini’s 24 Caprices for Solo Violin, Op. 1 (1802-1817) (approx. 72-89’) (list of recorded performances), “are considered the most technically and musically demanding works in the entire violin repertoire. They are rarely performed in concerts due to the high risk of technical inaccuracies occurring and are usually only attempted by celebrity violinists who have devoted their life to mastering the violin.” Yet they are not merely technical exercises. “The Caprices have an annoyingly clever balance of technique and musicality.” They “mark the outer limits of traditional violin technique”. Great recorded performances are by Ruggiero Ricci in 1950, Michael Rabin in 1955, Itzhak Perlman in 1972, Salvatore Accardo in 1977, Shlomo Mintz in 1981, Midori in 1990, Julia Fischer in 2005, Ilya Gringolts in 2007, James Ehnes in 2009, Kinga Augustyn in 2016, Augustin Hadelich in 2018, Ibragimova in 2021, and Dueñas in 2025.

Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau is widely renowned as the greatest art song singer in the era of recorded music, “A Born God' Among Singers”. His superb phrasing, tone, dynamic and linguistic expression, and his thoroughgoing understanding of the music sets him apart from other performers, however brilliant they were or are. His renditions of Schubert’s lieder are especially fine.

- Schubert, Winterreise, with Moore

- Schubert, Winterreise, with Brendel

- Schubert, Winterreise, with Pollini

- Schubert, lieder, with Moore

- Schubert, lieder, with Richter

- Schubert, Die schöne Müllerin, with Moore, 1972

- Schubert, Die schöne Müllerin, with Eschenbach, 1991

- Schubert, Schwanengesang (Swan Song)

- Brahms, 30 lieder, with Moore

- Brahms, 28 lieder, with Barenboim

- Schumann, lieder, with Höll, 1988

- Strauss, lieder, with Pleyel, 1964

- 1965 recital, with Richter

- Master class, 2003

Enrico Caruso is still widely regarded as history’s greatest operatic singer. He is the main subject of a documentary film. The large volume of his recordings, the latest being in 1921, attests to his exceptional talent.

Especially in his early career, before he suffered a shoulder injury in 2005, violinist Maxim Vengerov scaled the heights of technical mastery. More than perhaps any other violinist, he seemed to be at one with his instrument. His early albums include:

- “Maxim Vengerov” (1989) (73’);

- “Beethoven: Sonata No. 9 . . .” (1992) (60’);

- “Paganini: Violin Concerto No. 1; Waxman . . . ” (1992) (63’);

- “Mozart, Beethoven, Mendelssohn: Violin . . . ” (1993) (65’);

- “Virtuoso Vengerov” (1993) (67’);

- “Bruch, Mendelssohn: Violin Concertos” (1993) (51’);

- “Prokofiev & Shostakovich: Violin Concertos” (1994) (71’);

- “Tchaikovsky, Glazunov: Violin Concertos” (1995) (54’);

- “Sibelius, Nielsen: Violin Concertos” (1996) (70’);

- “Brahms: Violin Concerto . . . ” (1999) (62’);

- “Shchedrin: Concerto Cantabile . . . ” (2000) (61’);

- “Dvořák: Violin Concerto . . . ” (2000) (59’);

- “Vengerov & Virtuosi” (2001) (68’);

- “Beethoven: Violin Sonatas . . .” (2001) (61’);

- “Maxim Vengerov Plays Bach, Shchedrin . . . ” (2002) (67’);

- “Britten: Violin Concerto; Walton . . . ” (2003) (64’);

- “Lalo: Symphonie espagnole . . . ” (2003) (73’);

- “Beethoven: Violin Concerto; Romances” (2005) (65’).

Recently, singer Samara Joy and guitarist Pasquale Grasso have teamed, producing work that transcends previous boundaries in jazz music. Here they are (with Grasso’s trio) on July 25, 2021, at the Arts Center at Duck Creek (83’).

Compositions:

- Joseph Joachim, Violin Concerto No. 2 in the Hungarian Style, Op. 11 (1857) (approx. 35-47’): This concerto demands extraordinary virtuosity in the soloist.

- Judith Zaimont, ASTRAL . . . a mirror life on the astral plane . . . (2004, rev. 2009) (approx. 9-13’): "Slowly tracks the spirit's elevation through eleven stages, from expressive contemplation through unease and turbulence, to final arrival and affirmation."

- James Whitbourn, Luminosity (2008) (approx. 29’) is a song and dance cycle of choral works devoted to figures in Christianity: “The focus in all the elements is on transcendent beauty and eternal love.” (Bernard Robertson, from the liner notes to this album)

- Raga Kalavati (Kalawati) is a Hindustani classical raag for midnight, derived from a Carnatic rag. “The word Kalavati implies ‘the one adorned with the ‘kalas’ or ‘arts’. So Kalavati also refers to Goddess Saraswati, who is considered the Goddess of knowledge, wisdom and all forms of arts.” Performances are by Shivkumar Sharma, Budhaditya Mukherjee, Ajoy Chakraborty, and Nikhil Banerjee.

Albums:

- Miles Davis, “The Complete 1964 Concert”: “My Funny Valentine” (63’)

- Enrico Fazio Critical Mass, “Wabi Sabi” (2019) (62’) (when a critical mass is reached, old boundaries are transcended)

- Alice Coltrane, “Transcendence” (1976) (38’): “. . . the vision on display here is not so much a grand musical one as it is an intensely focused spiritual one, based upon a sacred Vedic text.”

- Matthew Shipp, “4D” (2010) (60’): “Altogether there are 16 cuts reflecting a wide range of approaches . . .”

- Tatjana Masurenko, “White Nights: Viola Music from Saint Petersburg” (2021) (176’)

- Tessa Lark, “The Stradgrass Sessions” (2023) (51’): “Bluegrass music played on a Stradivarius gives this album its title . . .” “Over the years, ‘Stradgrass’ has come to mean living and exploring distant violinistic styles through a classical lens, (Lark) explains.” “Lark’s accompanists, including jazz pianist Jon Batiste, bassist Edgar Meyer, fiddler Michael Cleveland and mandolinist Sierra Hull, are no less responsible for the enchantment.”

- Yazz Ahmed, “Paradise in the Hold” (2025) (70’) is an album of “boundary-transcending jazz . . .” “This record reminded me of why I appreciate music. It’s not just that it’s beautiful; it’s that Yazz Ahmed’s compositions make you feel like you’re on the coast of the Persian Gulf itself. You can hear the wind moving the sand, taste the salt of the sea, feel the heat of the Arabian sun, and see the glitter of that sun across the crystalline waters. Ahmed has created a record which is not only compositionally brilliant and progressive, but is steeped with all of the mystique and beauty of Arabia itself . . .”

- Noémi Györi, “Sinan C. Savaşkan: The Sleep of Reason - Music for solo flute & electronics” (2025) (53’): “Spanning nearly five decades of Savaşkan’s compositional output, the album explores the full expressive range of the flute—its lyric warmth, its structural clarity, and its capacity for sonic transformation—often in dialogue with subtly woven electronic elements. . . . (It) is a profound collaboration between two artists whose shared sensitivity reshapes what solo flute music can mean . . .”

Music: songs and other short pieces

- Paganini wrote his “Moto Perpetuo” for violin. Rafael Mendez and Sergei Nakariakov have played it spectacularly on trumpet.

- Prince, Tom Petty, Steve Winwood and Jeff Lynne, “While My Guitar Gently Weeps” (lyrics)

- Singer Samara Joy and Guitarist Pasquale Grasso, “Solitude” (lyrics)

Visual Arts

- Valentin Serov, Anna Pavlova in the Ballet Sylphide (1909)

- Edgar Degas, The Star (Dancer on Stage) (1876-77)